2 Kings 23: 1-3 Attempting to Recreate the Covenant

1 Then the king directed that all the elders of Judah and Jerusalem should be gathered to him. 2 The king went up to the house of the LORD, and with him went all the people of Judah, all the inhabitants of Jerusalem, the priests, the prophets, and all the people, both small and great; he read in their hearing all the words of the book of the covenant that had been found in the house of the LORD. 3 The king stood by the pillar and made a covenant before the LORD, to follow the LORD, keeping his commandments, his decrees, and his statutes, with all his heart and all his soul, to perform the words of this covenant that were written in this book. All the people joined in the covenant.

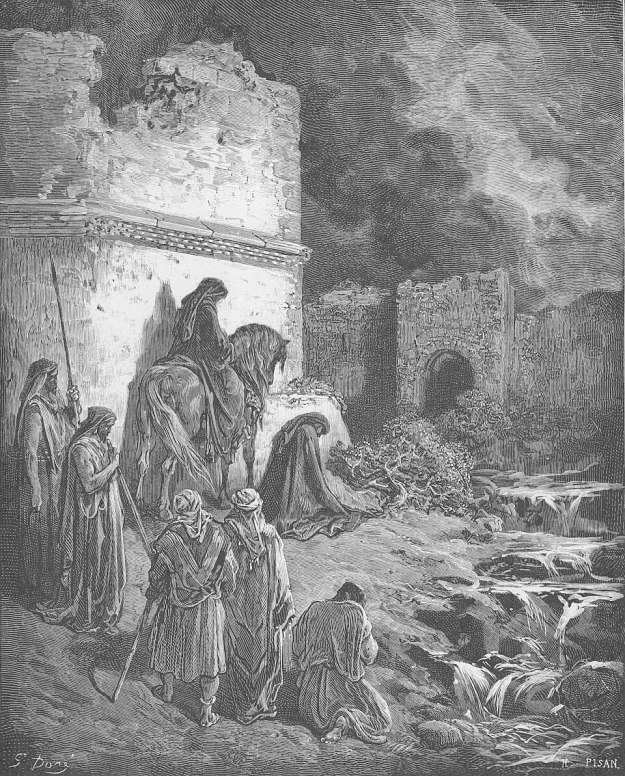

King Josiah responded to the rediscovered book of the law of Moses with repentance and seeking God’s will through the prophet Hulda. After learning that his understanding of the judgment that hangs over the people is confirmed by God and learning that God has seen and responded to the king’s action of mourning and repentance Josiah initiates his reforms by gathering the leaders and the people of Judah in an action to recommit the people to the covenant. The action echoes the creation of the covenant between God and the people by Moses (Exodus 24: 4-8), the recommittal to the covenant preceding Moses’ death (Deuteronomy 29:2-29)[1] and finally when Joshua renews the covenant in the promised land (Joshua 8:30-35). Throughout the narratives of the book of Judges, 1&2 Samuel, and 1&2 Kings this is the only instance of covenant renewal of this type. Other kings have attempted to renew the worship in the temple or the building of the temple, but only here in the time of kings are the people reconnected to the law in this manner.[2] This will also happen when the temple is rebuilt and the people are regathered in Jerusalem under the governor Nehemiah and the priest Ezra (Nehemiah 8). King Josiah seems to understand that his personal repentance may be enough for his own reign, but the only chance for the people lies in reestablishing the practices that were designed to make the people of Judah into the people of the LORD the God of Israel.

2 Kings 23: 4-14 Reforming the Practices in Judah

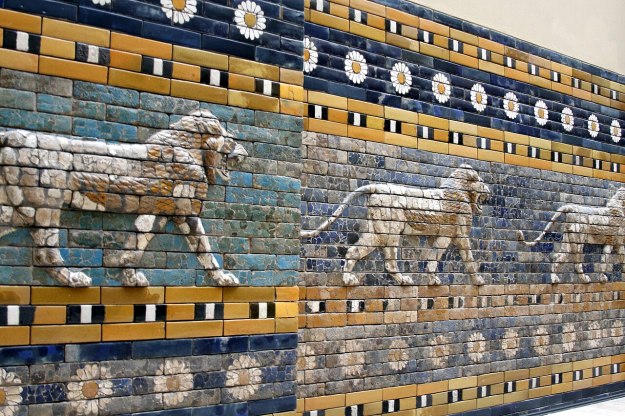

4 The king commanded the high priest Hilkiah, the priests of the second order, and the guardians of the threshold to bring out of the temple of the LORD all the vessels made for Baal, for Asherah, and for all the host of heaven; he burned them outside Jerusalem in the fields of the Kidron and carried their ashes to Bethel. 5 He deposed the idolatrous priests whom the kings of Judah had ordained to make offerings in the high places at the cities of Judah and around Jerusalem, those also who made offerings to Baal, to the sun, the moon, the constellations, and all the host of the heavens. 6 He brought out the image of Asherah from the house of the LORD, outside Jerusalem, to the Wadi Kidron, burned it at the Wadi Kidron, beat it to dust, and threw the dust of it upon the graves of the common people. 7 He broke down the houses of the illicit priests who were in the house of the LORD, where the women did weaving for Asherah. 8 He brought all the priests out of the towns of Judah and defiled the high places where the priests had made offerings, from Geba to Beer-sheba; he broke down the high places of the gates that were at the entrance of the gate of Joshua the governor of the city, which were on the left at the gate of the city. 9 The priests of the high places, however, did not come up to the altar of the LORD in Jerusalem but ate unleavened bread among their kindred. 10 He defiled Topheth, which is in the valley of Ben-hinnom, so that no one would make a son or a daughter pass through fire as an offering to Molech. 11 He removed the horses that the kings of Judah had dedicated to the sun at the entrance to the house of the LORD, by the chamber of the eunuch Nathan-melech, which was in the precincts; then he burned the chariots of the sun with fire. 12 The altars on the roof of the upper chamber of Ahaz that the kings of Judah had made and the altars that Manasseh had made in the two courts of the house of the Lord he pulled down from there and broke in pieces and threw the rubble into the Wadi Kidron. 13 The king defiled the high places that were east of Jerusalem, to the south of the Mount of Destruction, which King Solomon of Israel had built for Astarte the abomination of the Sidonians, for Chemosh the abomination of Moab, and for Milcom the abomination of the Ammonites. 14 He broke the pillars in pieces, cut down the sacred poles, and covered the sites with human bones.

The list of idolatrous images and practices that Josiah attempts to eradicate is encyclopedic in nature and paints the picture of the pervasive perversity of the people. Baal, Asherah, and the host of heaven have all been attractive alternatives for the leaders and people of Israel throughout their history as well as the worship at the high places by local priests and leaders who may not have been committed exclusively to the LORD. The ‘illicit priests’ (NRSVue) of verse seven is rendered ‘male prostitutes’ in many translations[3] and may indicate a linkage between some of these idolatrous religious practices and sexual practices. The list is similar to the list of abominable practices in the temple in Ezekiel 8 and it is likely that even during Josiah’s life many of these practices endured even if they were done in secret. Some of these idolatrous practices go back to the time of King Solomon (1 Kings 11: 1-13) and King Josiah forms a faithful contrast to Solomon. The actions of removing and destroying these idolatrous imagery and practices in a public and cultic manner is intended to purge these images from the practices of Judah. Josiah attempts to eradicate these practices, both long standing and recent, and attempt to recenter worship in a purged temple with administered by the priests who are faithful to the LORD in Jerusalem.

The reading of the covenant is not enough. Josiah seems to understand that only a complete abandonment of the idolatrous practices of his ancestors and the people may turn away the anger of the LORD. His work of purging the temple, the countryside, and the people is a model of what is expected in the law (Deuteronomy 12: 1-12), but despite the extreme actions to purge these images and practices from Judah the renewal will not survive his death. There is an optimism in the time of Josiah that is reflected in the prophet Jeremiah, but Jeremiah will also see that the reforms do not run deep enough and the people quickly return to the practices that Josiah attempted to eradicate.

2 Kings 23: 15-20 Reforming the Practices in Israel

15 Moreover, the altar at Bethel, the high place erected by Jeroboam son of Nebat, who caused Israel to sin—he pulled down that altar along with the high place. He burned the high place, crushing it to dust; he also burned the sacred pole. 16 As Josiah turned, he saw the tombs there on the mount, and he sent and took the bones out of the tombs and burned them on the altar and defiled it, according to the word of the LORD that the man of God proclaimed when Jeroboam stood by the altar at the festival; he turned and looked up at the tomb of the man of God who had proclaimed these things. 17 Then he said, “What is that monument that I see?” The people of the city told him, “It is the tomb of the man of God who came from Judah and proclaimed these things that you have done against the altar at Bethel.” 18 He said, “Let him rest; let no one move his bones.” So they let his bones alone, with the bones of the prophet who came out of Samaria. 19 Moreover, Josiah removed all the shrines of the high places that were in the towns of Samaria that kings of Israel had made, provoking the LORD to anger; he did to them just as he had done at Bethel. 20 He slaughtered on the altars all the priests of the high places who were there and burned human bones on them. Then he returned to Jerusalem.

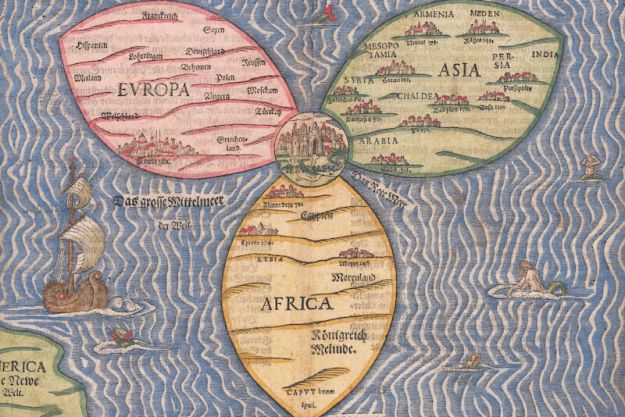

I intentionally separated this section from the previous section because the actions here are occurring in Northern Israel/Samaria. Jeremiah also indicates that during the time of Josiah there was a hope for a reunification of the two halves of Israel that had broken apart after Solomon (1 Kings 12). It is difficult to peer this far back into history since we have few historical witnesses from this point but it is plausible with Assyrian power in decline that Josiah may have had a window where he could assume control over portions of Northern Israel/Samaria and attempt to bring the people who now live there into the worship of the LORD. Bethel is mentioned, but the altar in Dan is not. However, the story takes us back to the strange story of the unnamed prophet who testifies against the altar at Bethel and foretells its destruction under Josiah and then is later buried in the city. (1 Kings 13) The method of defiling the altars that Josiah practices to bring about ritual uncleanness is not specifically outlined in the law, although contact with a dead body did bring about ritual uncleanness. The killing of the idolatrous priests, however, is consistent with the expectations of Deuteronomy 13: 13-19 for a man who has led people to follow other gods.

2 Kings 23: 21-23 Reestablishing the Passover

21 The king commanded all the people, “Keep the Passover to the LORD your God as prescribed in this book of the covenant.” 22 No such Passover had been kept since the days of the judges who judged Israel, even during all the days of the kings of Israel and of the kings of Judah, 23 but in the eighteenth year of King Josiah this Passover was kept to the Lord in Jerusalem.

Passover is the ritual that reminds the people of Israel of their identity, an identity that goes to the heart of the law. They are descendants of a people enslaved and liberated by the LORD’s powerful actions to deliver them from Egypt. This central festival in the life of the people of God is mentioned here for the first time in the books of 1 & 2 Kings and is not mentioned in Judges or 1 & 2 Samuel either. The last time the scriptures note the people celebrating the Passover prior to Josiah was in Joshua when the people celebrated at Gilgal.[4] There is an attempt to reconnect the people to their story through the renewal of the covenant, the removal of idolatrous alternatives, and the reinstatement of the rituals which help provide meaning. It is possible that Passover celebrations have continued through the story of Israel with or without royal institution, but I do believe that 2 Kings is attempting to show a drastic contrast between the loss of communal identity in the practices that surround the practice of the commandments, statutes, and ordinances of the law. Something central to the life of the people, in the view of 2 Kings, has been lost for many generations and for a brief window under Josiah there is the potential to rediscover the life the people were intended to live in the promised land.

2 Kings 23: 24-30 The Death of Josiah, a Final Word on both Josiah and Judah

24 Moreover, Josiah put away the mediums, wizards, teraphim, idols, and all the abominations that were seen in the land of Judah and in Jerusalem, so that he established the words of the law that were written in the book that the priest Hilkiah had found in the house of the LORD. 25 Before him there was no king like him who turned to the LORD with all his heart, with all his soul, and with all his might, according to all the law of Moses, nor did any like him arise after him.

26 Still the LORD did not turn from the fierceness of his great wrath by which his anger was kindled against Judah because of all the provocations with which Manasseh had provoked him. 27 The LORD said, “I will remove Judah also out of my sight, as I have removed Israel, and I will reject this city that I have chosen, Jerusalem, and the house of which I said, ‘My name shall be there.’ ”

28 Now the rest of the acts of Josiah and all that he did, are they not written in the Book of the Annals of the Kings of Judah? 29 In his days Pharaoh Neco king of Egypt went up to the king of Assyria to the River Euphrates. King Josiah went to meet him, but when Pharaoh Neco met him at Megiddo, he killed him. 30 His servants carried him dead in a chariot from Megiddo, brought him to Jerusalem, and buried him in his own tomb. The people of the land took Jehoahaz son of Josiah, anointed him, and made him king in place of his father.

Josiah’s actions to restore the nation of Judah to the expectations of the words of the law are shown in the book as an example of what a good king was expected to be. Yet all the works of Josiah are not enough to turn aside the anger of the LORD. They delay the anger and provide a window of perceived prosperity during the lifetime of this king but ultimately it seems that the wickedness of Manasseh have a greater impact on the future of the people than the reforms of Josiah. Josiah may be portrayed alongside Moses, Joshua, David, and Hezekiah as shining examples of leaders seeking God’s ways but ultimately these leaders were unable to undo the corruption among the people.

The prophet Jeremiah, when writing about the time of Josiah, shares the early optimism of what could be with this reformer king but quickly realizes that the reforms did not change the practices of the people. Josiah may be able to capture a hope of a reunification of Israel and a return to their previous relationship with their God but the rituals, the readings of the law, and the removal of the idols do not ultimately change the hearts of the people and the leaders who will follow him. Just as Hezekiah was followed by Manasseh, so Josiah will be followed by leaders who are unable or unwilling to continue his actions.

The Deuteronomic history and 2 Kings is written from the perspective of the exile of Judah and wants to understand how the people of Israel could fall from their pinnacle under David and Solomon to the moment where they are exiles in a foreign land. 2 Kings like the prophets Jeremiah and Ezekiel points to the wickedness of Manasseh but also a wickedness that goes back to Solomon’s betrayal under the influence of his wives. On the one hand, from the perspective of the narrator, the LORD has been incredibly patient with both Israel and Judah waiting for generations for them to live into their identity and willing to postpone God’s wrath for the sake of these moments of repentance. On the other hand, the narration of the unfaithful history of Judah and Israel in the words of 1 & 2 Kings helps to provide meaning and context for a people who have lost their land, their king, and their temple.

Josiah’s death occurs abruptly in the text and brings an end to this time of possibility. We can only hypothesize why Josiah would go out to meet Pharoah Neco at Megiddo. Assyria is in decline and by 610 BCE is beginning to lose ground to the Babylonians. Pharoah Neco at this time is a relatively new king and leads a force northward to help the Assyrians when Josiah meets him at Megiddo. Could Josiah be forming an alliance with Babylon against Assyria? It is possible. It is also possible that this king who has experienced success in regaining territory in Northern Israel to bring about the possibility of a reunited kingdom may view himself as divinely authorized to protect the land from any invasion even if Pharoah’s armies were only intending to pass through Judah on their way to the conflict in the north. Ultimately the critical reality is that Josiah dies at the hands of Pharoah Neco and this brings about the end of this final promising moment in the history of Davidic kings. Josiah is buried but ultimately does not die in peace as the prophet Huldah had stated and his death brings about the rapid descent of Judah towards its exile under Babylon.

2 Kings 23: 31-37 The Brief Reign of Jehoahaz and the Transition to Jehoiakim

31 Jehoahaz was twenty-three years old when he began to reign; he reigned three months in Jerusalem. His mother’s name was Hamutal daughter of Jeremiah of Libnah. 32 He did what was evil in the sight of the LORD, just as his ancestors had done. 33 Pharaoh Neco confined him at Riblah in the land of Hamath, so that he might not reign in Jerusalem, and imposed tribute on the land of one hundred talents of silver and a talent of gold. 34 Pharaoh Neco made Eliakim son of Josiah king in place of his father Josiah and changed his name to Jehoiakim. But he took Jehoahaz away; he came to Egypt and died there. 35 Jehoiakim gave the silver and the gold to Pharaoh, but he taxed the land in order to meet Pharaoh’s demand for money. He exacted the silver and the gold from the people of the land, from all according to their assessment, to give it to Pharaoh Neco.

36 Jehoiakim was twenty-five years old when he began to reign; he reigned eleven years in Jerusalem. His mother’s name was Zebidah daughter of Pedaiah of Rumah. 37 He did what was evil in the sight of the LORD, just as all his ancestors had done.

Jehoahaz, whose birth name seems to be Shallum[5] reigned for only three months before he was removed by Pharoah Neco and replaced by Jehoiakim as a more palatable leader to Egypt who now extends control over Judah and requires a heavy tribute[6] on the people. The death of Josiah has not only brought about an end to the reforms of his reign but has also changed the political situation of the people. We don’t know what Jehoahaz did in his three-month reign, which was evil in the sight of the narrator of 2 Kings, but his unfaithfulness is implied to be linked to the decline of the people as we move into the final two chapters of the narrative.

Jehoiakim, Josiah’s second born son, is chosen to succeed Jehoahaz by Pharoah Neco. This is an area where the chapter break would make sense to come two verses earlier since Jehoiakim’s story follows in the coming chapter. At this point it is worth noting the narrator’s judgment of Jehoiakim as one who did evil in the sight of the LORD and then end this discussion to resume his story in the following chapter.

[1] The narrative setting of the book of Deuteronomy paints the book as a witness of Moses’ public restatement of the law before the people which the people assent to at the end of the book.

[2] Many biblical scholars from the historical critical and source critical schools would argue that the law as we have it in Genesis-Deuteronomy is a later document. Their arguments are cogent, but ultimately, I do think it is likely that even if Genesis-Deuteronomy will reach their final form in the time of exile there is some pre-existing collection of the commandments which is active here and earlier through the story of Israel and Judah.

[3] The Hebrew qesesim refers to ‘sacred males.’ “It is an open question whether these persons were or were not male “cult prostitutes.” (Cogan, 1988, p. 286)

[4] Joshua 5: 10-12. 2 Chronicles 30 mentions a celebration of Passover under King Hezekiah, but in the Deuteronomic History (Joshua-2 Kings) this is the first mention since the time of Joshua

[5] Jeremiah 22: 11-12. 1 Chronicles 3:15 indicates that he was Josiah’s fourth son.

[6] A talent is around 70 pounds, so a tribute of roughly 7,000 pounds of silver and 70 pounds of gold in the text.