Matthew 22: 1-14

Parallel Luke 14: 15-24

Once more Jesus spoke to them in parables, saying: 2 “The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king who gave a wedding banquet for his son. 3 He sent his slaves to call those who had been invited to the wedding banquet, but they would not come. 4 Again he sent other slaves, saying, ‘Tell those who have been invited: Look, I have prepared my dinner, my oxen and my fat calves have been slaughtered, and everything is ready; come to the wedding banquet.’ 5 But they made light of it and went away, one to his farm, another to his business, 6 while the rest seized his slaves, mistreated them, and killed them. 7 The king was enraged. He sent his troops, destroyed those murderers, and burned their city. 8 Then he said to his slaves, ‘The wedding is ready, but those invited were not worthy. 9 Go therefore into the main streets, and invite everyone you find to the wedding banquet.’ 10 Those slaves went out into the streets and gathered all whom they found, both good and bad; so the wedding hall was filled with guests.

11 “But when the king came in to see the guests, he noticed a man there who was not wearing a wedding robe, 12 and he said to him, ‘Friend, how did you get in here without a wedding robe?’ And he was speechless. 13 Then the king said to the attendants, ‘Bind him hand and foot, and throw him into the outer darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.’ 14 For many are called, but few are chosen.”

This final parable continues to be challenging for many modern readers of Matthew who struggle with the wrathful king’s judgment on both those who reject their calling and on the improperly attired guest. Many scholars who view the versions of this parable in Matthew and Luke coming from a common source argue that Luke’s easier to reconcile version is closer to the parable that Jesus originally told as a way of distancing themselves from the portions of the parable which make them uncomfortable. Yet, Matthew’s version uses several prophetic motifs which are probably unfamiliar to many modern readers of the New Testament which are worth slowing down to engage and hear. Perhaps Matthew has something to teach our communities about the way we attempt to eliminate God’s judgment because it is uncomfortable for people living in peaceful, affluent communities very different from either Jesus or Matthew’s time.

Matthew groups parables together in a way that they build upon one another in a group of three. In hearing this parable, it is important to place it alongside the previous two vineyard parables (two sons and wicked stewards) as Jesus uses a new image, that of a wedding banquet. While there are images in Israel of people being invited to a great feast prepared by God for people, perhaps the best known coming in Isaiah 25: 6

On this mountain the LORD of hosts will make for all peoples a feast of rich food, a feast of well-aged-wines, of rich food filled with marrow, of well-aged-wines strained clear.

Yet, the idea that this feast is a wedding celebration is unique to Matthew and there is not an echo of God throwing a wedding banquet that I am aware of in either the Hebrew Scriptures or the Apocrypha. Yet, Matthew has used this image previously in 9:15 with Jesus referring to his disciples’ conduct during his presence among them:

And Jesus said to them, “The wedding guests cannot mourn as long as the bridegroom is with them, can they? The days will come when the bridegroom is taken away from them, and then they will mourn.”

This image of a wedding celebration will also link this parable to the first parable in the next and final set of parables in 25: 1-13. The parable links both images of the feast of rich foods prepared by God for all people and with the identity of Jesus as the bridegroom and son of the king in Matthew.

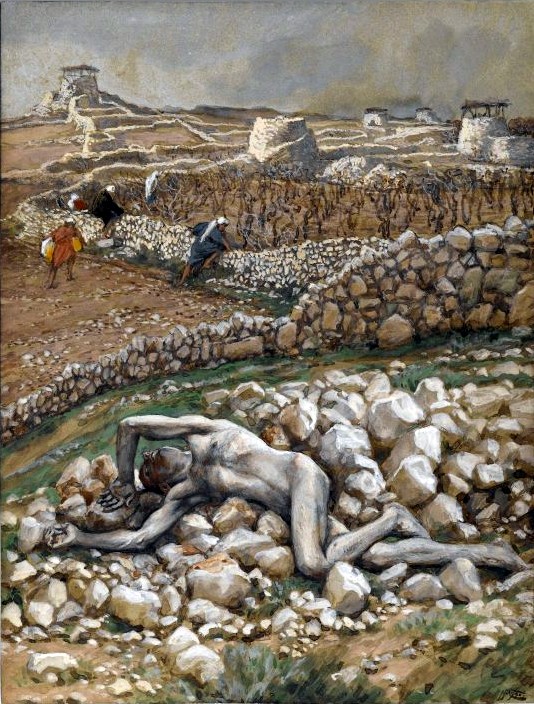

Yet, the story turns upon the rejection of the call of those who are called. The Greek work kaleo (to call) occurs frequently throughout this narrative as the king sends his slaves to call the ones ‘having been called.’ In our culture we think of invitations as optional, but these who have been called to appear by the king and snub that call by extension reject the authority of the king to summon them. As Warren Carter notes, “Refusing the king’s invitation is tantamount to rebellion.” (Carter 2001, 434) This is heightened by the action of those who seize, mistreat, and kill the slaves sent[1] who like the vineyard workers in the previous parable invite, and in the answer of the hearers of the previous parable require the ‘housemaster’ and now the king to “put those wretches to a miserable death.” (21:41)

The wrath[2] of the king is perhaps difficult to many modern readers who are used to thinking about God as unemotional or immovable, but these modern conceptions of God are based more on Greek philosophical ideals rather than the God of the scriptures. A God who sends his loyal slaves over and over with the hope of a harvest or the invitation to the celebration of the wedding of his Son, only to see these slaves mistreated and killed is compelled to act on behalf of the slaves. If, as most interpreters assume, Matthew is using this parable as an explanation of the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple by Rome in 70 CE (destroyed those murders and burned their city) they seem unable to reconcile this God who invites with the God who destroys. Yet, perhaps this says more about our unwillingness to stand under God’s judgment or our desire to take judgment into our own hands. That God’s troops would include the Roman legions which destroyed Jerusalem, who like Babylon and Persia previously had served God’s purposes without knowing it, should not surprise, nor should the experience of God’s people receiving judgment for being unwilling to respond to God’s continued call.

I am not a fire and brimstone preacher, as a Lutheran pastor I’d rather focus on the grace of God, but I’ve also come to understand that the wrath of God or anger of God is not the opposite of God’s grace. God is angry because God care: God cares about the slave sent to carry the message, God cares about the wedding banquet which they have been invited to, and, although it may seem strange to modern ears, God does care about the called ones. The God of Israel may be patient and slow to anger, but this God will not be taken for granted. God continues to desire repentance and is willing to continue to send those precious to God to seek a change, but eventually God’s patience becomes too costly for those who carry God’s message, and like the saints under the altar in Revelation 6: 9-11 they cry out,“Sovereign Lord, holy and true, how long will it be before you judge and avenge our blood on the inhabitants of the earth.”

That Jesus, and Matthew, understand God at work in the movement of the nations is a part of the bold claim of the faith of Israel that their God is not only their God, but the creator of the world and the Lord over all nations. This may be challenging for modern believers who have separated the spiritual world from the political world and who may be slightly embarrassed to suggest that God can be at work in the world in strange and mysterious ways, but that also highlights the way culture has changed our faith. The early followers of Jesus could trust that God’s kingdom would come into the world, that God’s will would be done on earth just as they assumed it was done in heaven. This is faith was an openness to perceive the ways that God was at work in the world, an awareness of the time they found themselves within with the bridegroom, and a trust that while God will is ultimately good for them, for the people of God and for all the nations, God the creator of the world should neither be tamed or domesticated into a household god that served the desires of those who called upon the name of the Lord.

There is a common strand with this parable and wisdom literature where the character of wisdom is not heeded:

Because I have called and you refused, have stretched out my hand and no one heeded, and because you ignored my counsel and would have none of my reproof, I also will laugh at your calamity; I will mock when panic strikes you, when panic strikes you like a storm, and you calamity comes like a whirlwind, when distress and anguish come upon you. Then they will call upon me, but I will not answer; they will seek me, but will not find me. Proverbs 1: 24-28 (see also Proverbs 8:35-36 and Jeremiah 6:16-17)

There is an call from their God (or from Wisdom on behalf of God) which is refused, and although the call is extended with the hope that the called ones will finally turn (or repent) the continued reality of rejection is not met with indifference by God. Yet, this rejection can also be used in strange ways to extend the invitation to others. In the parable now the slaves are sent to the crossroads or the roads leading out of town to gather everyone to the banquet, both good and bad, filling the wedding celebration with guests. Just as the tax collectors and prostitutes heard John the Baptist’s message and turned even though the Pharisees and Sadducees did not (21:31) now those on the streets find themselves in the wedding hall.

The final scene of this parable, unique to Matthew, with the guest not wearing the proper attire has also caused distress for many readers for the same reason as the earlier judgment, and again many scholars want to view this as an addition to the original parable of Jesus, but before we pass judgment on it, perhaps we should hear it out. Just as the rejection by the ones called to the banquet was tantamount to rebellion, so is being present in a way that is disrespectful to the host. We often assume referring to someone as ‘friend’ assumes intimacy, but in Matthew’s gospel, and in ancient cultures, it can imply a power differential or distance between the speaker and hearer. (20:13, 26:50) The fact that one is invited later does not give one permission not to heed counsel or ignore reproof, and as Matthew’s gospel has focused on building a community of Christ where the actions of the individuals in the community matter, just as the original invitees can find themselves encountering their king’s wrath, so can the newly invited.

One final word, Matthew’s gospel paradoxically is viewed both as the most Jewish and the most hostile to the Jewish people, since these parables and many other things we will encounter in these final chapters have often been read in a supersessionist way by Christians. I will continue to address this as we move through these final chapters, but it is important to note that in this parable those invited are still a part of the king’s original people, not from new nations, and throughout these parables what are sought are more responsive sons, tenants, and subjects, not a new people. Much of Jesus’ conflicts will be with the chief priests, the scribes, the elders, the Sadducees and the Pharisees and not with the people as a whole, and Jesus’ life from the beginning of Matthew is to, “save his people from their sins.” (1:21) That Jesus, like the prophets (or in the parables slaves), who went before him challenges the leaders of the people is a part of the reason the people are able to see him as a prophet, and like the prophets his calls often fall upon ears that cannot hear. Yet, I think Matthew would echo Paul when he says to Gentile Christians who came to be a part of the community of Christ:

But if some branches were broken off, and you, a wild olive shoot, were grafted in their place to share the rich root of the olive tree, do not boast over the branches. If you do boast, remember that it is not you that support the root, but the root that supports you. You will say, “Branches were broken off so that I might be grafted in.” That is true. They were broken off because of their unbelief, but you stand only through faith. So do not become proud, but stand in awe. For if God did not spare the natural branches, perhaps he will not spare you. Romans 11: 17-21

[1] The word for sent is the verb apostello where we get our English apostle (sent ones).

[2] This is the Greek orgizo, which is the verbal form of orge, which often is used to refer to the wrath of God in judgment against God’s people (for example in Exodus) or upon those in continued rebellion in Revelation.