Psalm 115

1 Not to us, O LORD, not to us, but to your name give glory, for the sake of your steadfast love and your faithfulness.

2 Why should the nations say, “Where is their God?”

3 Our God is in the heavens; he does whatever he pleases.

4 Their idols are silver and gold, the work of human hands.

5 They have mouths, but do not speak; eyes, but do not see.

6 They have ears, but do not hear; noses, but do not smell.

7 They have hands, but do not feel; feet, but do not walk; they make no sound in their throats.

8 Those who make them are like them; so are all who trust in them.

9 O Israel, trust in the LORD! He is their help and their shield.

10 O house of Aaron, trust in the LORD! He is their help and their shield.

11 You who fear the LORD, trust in the LORD! He is their help and their shield.

12 The LORD has been mindful of us; he will bless us; he will bless the house of Israel; he will bless the house of Aaron;

13 he will bless those who fear the LORD, both small and great.

14 May the LORD give you increase, both you and your children.

15 May you be blessed by the LORD, who made heaven and earth.

16 The heavens are the LORD’s heavens, but the earth he has given to human beings.

17 The dead do not praise the LORD, nor do any that go down into silence.

18 But we will bless the LORD from this time on and forevermore. Praise the LORD!

Martin Luther when talking about the first commandment explained the commandment on having no other gods by stating, “We are to fear, love, and trust God above all things.” Psalm 111 ended with “the fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom.” Now Psalm 115 centers on trusting the LORD. Chris Tomlin’s contemporary Christian song “Not to us” takes the first verse of this song and constructs a song around the first half of the verse, but if we were to construct a modern song based on the central idea of this psalm it would use verses nine through eleven as the chorus. Structurally this psalm centers on the call for Israel, the house of Aaron, and those who fear the LORD to trust the LORD who will help and protect them.

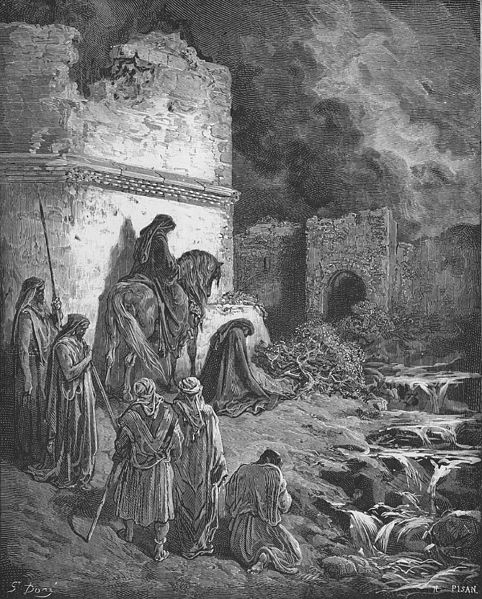

The psalm begins with a call for the name of the LORD to be given its proper glory, honor, and respect. On the one hand, this does reflect the proper posture of humility for the worshipper of the LORD and calling on the actions of God and the actions of the worshipping community to be solely for God’s glory. On the other hand, throughout the Hebrew Scriptures when the people call upon God to act for the sake of God’s name they have frequently been unfaithful and unworthy of God’s redemption and rescue. The argument is frequently made by the people that the disaster that has come upon them has brought dishonor to the reputation of God. The psalmist knows that the LORD is a God of steadfast love (hesed) and faithfulness. Yet the nations look at Israel and wonder where is their God? They may be looking upon the disaster that has occurred among the people and wonder if the LORD is absent or impotent. The psalmist protests that God is able to do whatever God pleases and that God rules from the heavens and unlike their neighbors in Canaan or Babylon they do not need, nor are they allowed to create, images of silver or gold.

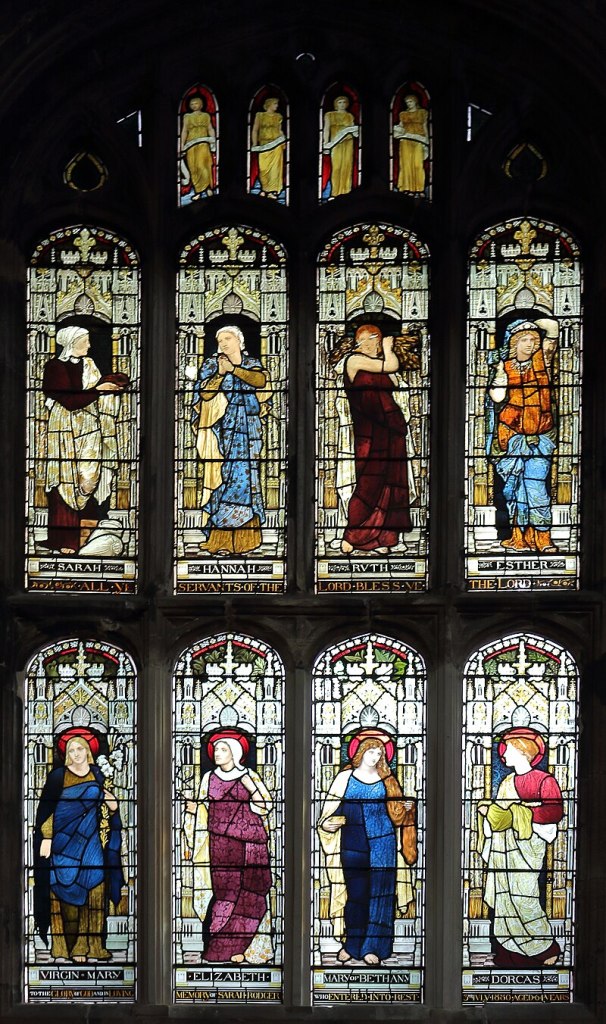

The faith of Israel was centered on the God who forbade the constructions of images that would attempt to capture the image of God. The mocking of idols here resonates with Isaiah’s taunts in Isaiah 44: 9-20 which come from the time of the Babylonian exile. The faith of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim creates a worship space that looks very different from many other religions. My congregation sits next to a large Hindu temple and their worship space is configured around the images that are central to their practice. The world of both Canaan and Babylon (and oftentimes the practice inside Israel and Judah) were filled with alternative ‘gods’ and alternative ways of worship and practice. These practices of worshipping other gods also led to a different way of relating to the world and the neighbor. For the Jewish people their faith was a faith tied to the law (Torah) which envisioned a very different society than most societies we are aware of in the ancient world.

The polemic against idols is, as James Mays reminds us, “to chastise and correct the congregation itself in support of the first and second commandment.” (Mays, 1994, p. 367) The congregation of Israel was to focus on its own practices and be an example for the nations. Yet, Israel just like people of faith of all times struggled to trust in the LORD above all things. The psalm takes the people back to the heart of their faith, trusting the LORD who helps and protects them. There will always been temptations to trust in one’s acquired wealth, work, alliances, connections, or physical or military strength. Israel was never a world power with a large enough military to stand against the Egyptian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Greek, or Roman empires in their times. Throughout their history they were looked upon as an oddity. Both Jews and early Christians were sometimes viewed as atheists because they had no images for their God and they refrained from the practices of their neighbors to attempt to remain faithful to their God.

The heavens are the LORD’s but the earth has been given as a gift to human beings. One of the aspects of biblical faith is the understanding of the earth and our place within it as a gift. The God who created the earth continues to provide for not only the faithful ones but all the people and creatures of the earth. Those who fear the LORD know trust that they will experience God’s blessing of provision in both their fields and their families.

The psalm closes with the note that the dead do not praise the LORD. Throughout most of the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament) there is no view of the dead going to heaven or hell. When a place of the dead is mentioned, it is often utilized to bargain with God because the dead cannot praise God.[1] The focus of the Hebrew Scriptures is on life being lived in covenant with God and trusting that God will provide for that life.

This psalm is about trust and praise being directed toward the God of Israel. From the perspective of the scriptures this is the way of a wise life. Those who follow idols and their ways are foolish. It is a call for those who have directed their trust and praise elsewhere to repent and return to the path of wisdom. Idols do not need to be the creations of gold and silver that the psalmist references. In the United States we are taught in multiple ways to ensure our security through wealth, power, fame, education, and work. None of these things are evil, but when our trust relies on these things instead of the LORD our faith is misplaced. The psalm shares a similar concern with Joshua at the end of his time leading the people where he challenges the people to choose which path and which gods they will follow. “As for me and my household, we will serve the LORD.” (Joshua 24:15) was Joshua’s challenge which the people answered that they also would serve the LORD. The people of Israel as well as the church continually has to remind itself that serving the LORD is very different from the alternative visions of faith present in the world. The psalm reminds me that we are to fear, love, and trust God above all things.

[1] See also Psalm 6:5.