Lamentations 1

1How lonely sits the city that once was full of people! How like a widow she has become, she that was great among the nations! She that was a princess among the provinces has become a vassal.

2She weeps bitterly in the night, with tears on her cheeks; among all her lovers she has no one to comfort her; all her friends have dealt treacherously with her, they have become her enemies.

3Judah has gone into exile with suffering and hard servitude; she lives now among the nations, and finds no resting place; her pursuers have all overtaken her in the midst of her distress.

4The roads to Zion mourn, for no one comes to the festivals; all her gates are desolate, her priests groan; her young girls grieve, and her lot is bitter.

5Her foes have become the masters, her enemies prosper, because the LORD has made her suffer for the multitude of her transgressions; her children have gone away, captives before the foe.

6From daughter Zion has departed all her majesty. Her princes have become like stags that find no pasture; they fled without strength before the pursuer.

7Jerusalem remembers, in the days of her affliction and wandering, all the precious things that were hers in days of old. When her people fell into the hand of the foe, and there was no one to help her, the foe looked on mocking over her downfall.

8Jerusalem sinned grievously, so she has become a mockery; all who honored her despise her, for they have seen her nakedness; she herself groans, and turns her face away.

9Her uncleanness was in her skirts; she took no thought of her future; her downfall was appalling, with none to comfort her. “O LORD, look at my affliction, for the enemy has triumphed!”

10Enemies have stretched out their hands over all her precious things; she has even seen the nations invade her sanctuary, those whom you forbade to enter your congregation.

11All her people groan as they search for bread; they trade their treasures for food to revive their strength. Look, O LORD, and see how worthless I have become.

12Is it nothing to you, all you who pass by? Look and see if there is any sorrow like my sorrow, which was brought upon me, which the LORD inflicted on the day of his fierce anger.

13From on high he sent fire; it went deep into my bones; he spread a net for my feet; he turned me back; he has left me stunned, faint all day long.

14My transgressions were bound into a yoke; by his hand they were fastened together;

they weigh on my neck, sapping my strength; the LORD handed me over to those whom I cannot withstand.

15The LORD has rejected all my warriors in the midst of me; he proclaimed a time against me to crush my young men; the LORD has trodden as in a wine press the virgin daughter Judah.

16For these things I weep; my eyes flow with tears; for a comforter is far from me,

one to revive my courage; my children are desolate, for the enemy has prevailed.

17Zion stretches out her hands, but there is no one to comfort her; the LORD has commanded against Jacob that his neighbors should become his foes; Jerusalem has become a filthy thing among them.

18The LORD is in the right, for I have rebelled against his word; but hear, all you peoples,

and behold my suffering; my young women and young men have gone into captivity.

19I called to my lovers but they deceived me; my priests and elders perished in the city

while seeking food to revive their strength.

20See, O LORD, how distressed I am; my stomach churns, my heart is wrung within me, because I have been very rebellious. In the street the sword bereaves; in the house it is like death.

21They heard how I was groaning, with no one to comfort me. All my enemies heard of my trouble; they are glad that you have done it. Bring on the day you have announced, and let them be as I am.

22Let all their evil doing come before you; and deal with them as you have dealt with me because of all my transgressions; for my groans are many and my heart is faint.

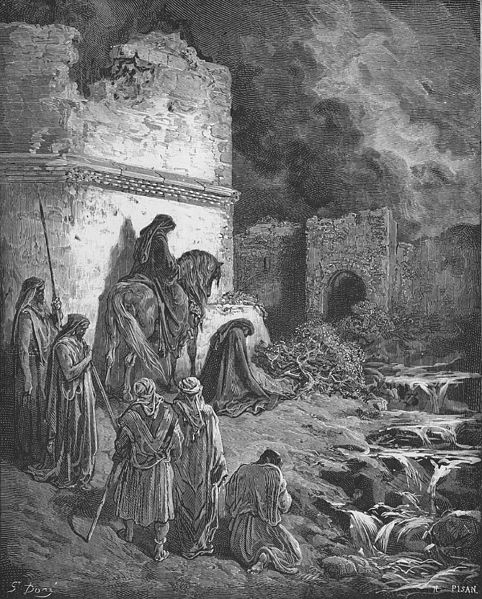

Poetry can be used to speak to things that are at the edge of our ability to articulate. It can be utilized to speak to moments of profound joy, of awe and wonder, of emotions like love and happiness whose meanings seem to transcend our words. Yet poetic words can be utilized in our moments of heartbreak, depression, grief, and trauma as we attempt to make sense of a world which seems senseless. Lamentations is the work of a poet or poets attempting to make sense of their reality in the aftermath of the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BCE. The poet has seen death from war and starvation, has seen the foundations upon which their life was built collapse, and the LORD who was supposed to protect Zion has turned away. The poet attempts to make sense of the loss of the home they knew, grieve the family and friends who did not survive the siege and the beginning of the exile, and to walk among a shattered people with shattered dreams into a previously unimagined reality.

The survivors of Jerusalem not only retained the words of the prophets who warned of this reality, but they also retained the words of the prophets and poets wrestling with God, attempting to reconcile their faith with the world they experience. They are living in a disordered world, and yet in their words they attempt to bring some order into the disorder. Kathleen O’Connor in her book Jeremiah: Pain and Promise talks about the way these works written in the time surrounding the exile invite not only the contemporary generation but also future generations to enter the process of being meaning-makers.

It not only reflects the interpretive chaos that follows disasters, when meaning collapses and formerly reliable beliefs turn to dust. Jeremiah’s literary turmoil is also an invitation to the audience to become meaning-makers, transforming them from being passive victims of disaster into active interpreters of their world. (O’Connor, 2011, p. 31)

Making sense of a traumatic world-changing event is not an overnight process. It is a journey through the dark shadows of grief and fear, depression and guilt, the struggle to survive as others surrender to the end. This first poem in the book of Lamentations attempt to bring some order to the disorder and give voice to the pain and humiliation felt by the people. They, like Jeremiah and Ezekiel, understand that the tragedy is a result of their own rebellion and disobedience which have broken their relationship with the LORD who protected them. They also understand that they have no future without the LORD looking, seeing, and considering the fate of this disgraced and displaced people.

The poem has two voices, a narrator and daughter Zion. The narrator is the primary speaker for the first half of the poem and attempts to relate the fate of daughter Zion as an observer of the fall of this city personified as a woman. The poem begins with the interrogative “How?” Although in English translations the word how is used primarily as an inquiry about the state of daughter Zion: How lonely, How like a widow. The word also inquires about the manner or way in which something comes to pass: How did it happen that lonely sits the city, How did she become like a widow? How did this place of honor among the nations become dishonored? How did the princess become the vassal? What has brought about this reversal for daughter Zion and those who made their home in this great city. Something has changed that has brought about the reversal of fortunes for the city and the people.

The narrator voice in the poem has a greater detachment from the suffering and events occurring to daughter Zion. Daughter Zion may weep, but the narrator reports. Yet, the narrator’s reports begin to allude to the reason why daughter Zion weeps. In a world where women were not to have lovers, they were to be faithful to their husband, now this one who has become like a widow[1] we learn is also abandoned by her lovers and friends. Something has gone wrong in the relationships that were supposed to provide support. The narrator slips out of the metaphor to narrate Judah’s entry into exile and the suffering that comes with her displacement from the promised land into the hostile nations. The exclamation that Judah found no resting place echoes the language of the curses for disobedience in Deuteronomy 28:65. As Lamentations, like Ezekiel and Jeremiah, make sense of the catastrophe of the Babylonian exile the utilize the theological perspective of Deuteronomy.

Now the roads that pass through Jerusalem mourn the loss of the pilgrim traffic to the festivals, and the priests who officiated at the festivals groan as the young women grieve. The young women here are teenage women of marriageable age. These may be the women at greatest risk of sexual violence from the enemy soldiers who have breached the city and who now escort them into exile. They also would be the women whose potential partners died in the defense of the city or in the aftermath of the breach. Daughter Zion now returns to the poem as one with a bitter lot, whose foes are now her master, whose enemies prosper. The reason is for the first time explicitly stated by the narrator: she is being made to suffer by the LORD for her transgressions. Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Lamentations all share a common perspective on the disastrous events. The tragedy of the siege, destruction, and exile are all a result of Judah’s disobedience to God and the curses of Deuteronomy 28 echo throughout Lamentation’s poetic remembrance.

Yael Zigler has a powerful explanation of the poetic image of the princes being like stags which find no pasture:

The verse portrays the previously powerful leadership as drained of energy, unable to find pastures or the basic means of survival. If they cannot find pasture for themselves, they certainly cannot help their people, whose sufferings are compounded by their leaders’ impotence. (Ziegler, 2021, p. 92)

Nobles, priests, and elders all failed the people in this crisis, but now they are unable to even deliver themselves. Both Jeremiah and Ezekiel had harsh words for these leaders who failed to care for the people and who compounded the upcoming crisis, but now as the world is turned upside down the powerful in Jerusalem are now impotent.

As the image once again returns to Jerusalem personified as mourning over her past riches and glories. She is isolated among the nations. Lamentations adopt a similar image to Hosea 1-3, Jeremiah 2–4, and particularly the harsh language of Ezekiel 16. Jerusalem’s past actions have led those who once admired her to despise her. Like the imagery of Ezekiel 16:35-43, Jerusalem is like a woman who is shamed by having her clothing taken away as an act of humiliation. The language of uncleanness enters the poem for the first time, but the uncleanness is literally in her hems at the bottom of her clothing. Whether the poem imagines her walking through the uncleanness of the world around her and it clinging to the skirts or whether it utilizes the image of menstruation[2] (which will come up with uncleanness later in the poem) without rags to catch the blood. Regardless of how exactly her uncleanness is visualized in the imagery of the poem, from the narrator’s perspective her actions which took no thought of the future, are the reason for her humiliated state. Her fall from grace was appalling and former friends and lovers are distant as daughter Zion for the first time raises her voice in the poem calling out to the LORD to “look at my affliction, for the enemy has triumphed!”

The narrator concludes his portion of the poem with the enemies of Zion taking her precious things and invading her sanctuary. Nations that were not to be a part of the congregation of Israel in the law now stand in the center of the temple where even priests would not enter. The language behind invade, often rendered “come into,” often denotes sex in the Hebrew scriptures and the poetic intent of the imagery may be to communicate that this is both the pillaging and rape of Zion. (Goldingay, 2022, p. 67) Daughter Zion is stripped, humiliated, dishonored, and disgraced as her people struggle to find the food, they need for the strength to endure the ravages of the siege and now exile. For most of the first half of the poem the narrator has described her sorry state, but now she turns to the LORD and to those who see her and raises her voice to command people to look, see, and consider her.

Rather than cowering in her pitiful state, daughter Zion lifts her voice and demands to be seen. The first one she cries to is the LORD to see the state that the LORD’s fierce anger has left her in. Then she cries to those who pass by to look and see her sorrow. Former friends and lovers who pass by ashamed of her are commanded by daughter Zion to see her in all her suffering and to understand the reason for her suffering. Her betrayal of the LORD has resulted in the LORD’s actions. As Kathleen O’Connor narrates,

Using vivid, violent verbs; she relates Yahweh’s brutal treatment of her. He sent fire; he spread a net; he turned her back; he left her devastated. Divine attacks of the female body again serve as a metaphor for the destruction of the city. (NIB VI: 1033)

In addition to the violent verbs listed above, the transgressions become a yoke which daughter Zion bears. The harsh language of daughter Zion’s appeal may also be designed to call upon the LORD to again assume the protector role. She now is the vulnerable one who needs the protection of the LORD. Like in the Psalms, the LORD may be both the cause of their suffering and the only one who can end the suffering.

The warriors, young men, daughters, and children of Zion now bear the crushing weight of the defeat of Zion by her foes. Warriors and young men have been crushed in the crucible of war and starvation, and in an image that will resonate in Isaiah 63, Joel 3, and Revelation 14 now “girl daughter Judah” is treaded as in a wine press. Daughter Zion weeps, and there is no one to comfort her or wipe away her tears. Children, perhaps orphaned by war or the first to suffer from starvation, are a prime example of the vulnerable caught in situations they cannot control.

In verse seventeen the narrator interrupts daughter Zion’s cries. This narrator can describe her isolation where no one will comfort her because the LORD has commanded her neighbors to become her foes. Yet, even beyond foes Jerusalem has become a “filthy thing” among them. “Filthy thing” (NRSV) or “unclean thing” (NIV) translates the Hebrew term nidda which refers to a “menstrual rag.” As Kathleen O’Connor states daughter Zion, “is not only ritually unclean, but she is also repulsive and dirty.” (NIB VI: 1033) Yet, rather than refute the narrator’s claim daughter Zion proclaims, “the LORD is in the right.” The woman does not deny that her suffering is justified but she also cries out the peoples once again to look and see her sufferings. Her bowels churn and her heart is wrung and death reigns both in the house and in the streets.

The enemies of Zion have seen and heard but their reaction is one of joy. In one final appeal the woman asks for the LORD to judge these enemies. That they may be judged as she was judged. That their evil may come before the LORD as her own rebellion came before the LORD. The LORD has dealt fairly if violently with her, now dealing in a similar fashion with those who abuse and taunt her. With a groaning body and a faint heart, she appeals to God out of her desolation asking for her God to look, see, and consider her words.

This acrostic poem utilizes the voice of a narrator and daughter Zion to express the pain and desolation of the collapse of the world as the people of Jerusalem gives words to the trauma of the exile. Like reading Elie Wiesel’s Night it allows a reader to encounter a small part of the tragic reality that the author encounters. Its language may at times make us uncomfortable, but we should never feel comfortable looking into the courageous act of someone trying to use words to express the inexpressible depths of their pain, their attempts to reimagine the relationship between themselves and their God in the midst of an earthshattering tragedy, and their attempts to make sense in a senseless world. One appeal of the acrostic form is that it imposes order on a chaotic world.

Any time we engage with the scriptures it is helpful to remember that there is some distance between the worldview of the exiles of Jerusalem in 586 BCE and ourselves. To appreciate the courage of the poet in their attempt to make sense of the world with words does not require us to fully endorse the use of vivid, violent verbs against a metaphorical female body. Although I cannot speak with authority about the view of masculinity of this time, I do believe one of the intentional uses of this language is to invoke in the LORD, who plays the masculine role in this imagery here and throughout the prophets, the role of protector. Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Lamentations do not shirk from the perspective that Jerusalem’s punishment is justified but that does not prevent Jeremiah, Lamentations, and the Psalms[3] from calling out to the LORD to look, see, consider and to respond in mercy.

The first poem of Lamentations may be able to articulate the pain of daughter Zion, but it is unable to resolve that pain. Even though the poet has worked through their crisis from aleph to tav, the acrostic poem has not brought about a complete expression of the pain. Perhaps that leads to the second poem which also speaks out of the pain of defeat, grief, and an uncertain future. These poems are steps on the way to healing. They are the articulation of the pain and loss of the people of Jerusalem. The loss of home, the loss of identity, the loss of meaning. Yet, in a strange way, these poems are a part of the rediscovery of faith. The LORD is the focal point of daughter Zion’s appeal. Daughter Zion hopes for a future beyond the anger of the LORD in this moment which has brought such devastation and disgrace.

[1] Widows in the bible are not only women who have lost their husbands but also people who have lost familial support and are therefore vulnerable. A person may be a widow and have a son or son-in-law to take her into her house, but widows as a vulnerable portion of the population (like orphans and strangers/resident aliens) would be those outside the familial support structure. (NIB VI: 1029)

[2] This may be a source of discomfort for modern readers, but menstruation occupies a significant place in the law in relation to cleanness and uncleanness. Similar language appears in the prophets.

[3] Ezekiel rarely appeals to the LORD for mercy. Ezekiel tends to value obedience to the LORD and rarely protests like his older colleague Jeremiah.