Psalm 122

A Song of Ascents

1 I was glad when they said to me,

“Let us go to the house of the LORD!”

2 Our feet are standing

within your gates, O Jerusalem.

3 Jerusalem—built as a city

that is bound firmly together.

4 To it the tribes go up,

the tribes of the LORD,

as was decreed for Israel,

to give thanks to the name of the LORD.

5 For there the thrones for judgment were set up,

the thrones of the house of David.

6 Pray for the peace of Jerusalem:

“May they prosper who love you.

7 Peace be within your walls

and security within your towers.”

8 For the sake of my relatives and friends

I will say, “Peace be within you.”

9 For the sake of the house of the LORD our God,

I will seek your good.

Bolded words have notes on translation below.

If we look at the first three songs of ascent in order (Psalm 120-122) there is a suggestive narrative. The psalmist begins in a place far from the city of peace surrounded by those who desire war (Psalm 120). The psalmist then departs on a journey lifting up their eyes to the hills (Mount Zion-Psalm 121). In this third song of ascent the psalmist arrives at their destination of Jerusalem. (NIB IV:1183) This song of thanksgiving upon arriving in the city of Jerusalem, the spiritual center of their world captures the joy of a pilgrim upon reaching their long-awaited destination.

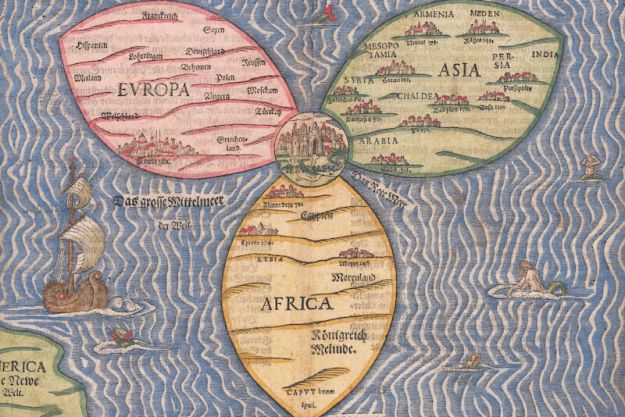

Both Isaiah 2: 2-3 and Micah 4:1-4 envision Jerusalem as being the spiritual center of the world for Jews and Gentiles, where the nations see the people living in harmony with God’s will for the world and they come to the mountain of God seeking instruction. Jerusalem becomes the pivot for a complete reordering of power in the prophetic imagination as swords become plowshares and spears become pruning hooks. The city of shalom (Jerusalem) becomes a light on the hill that the nations are drawn to learn God’s ways of peace.

The psalm is structured around the two houses that reside in Jerusalem: the house of the LORD and the house of David. The house of David occupies the central verse of the poem structurally, and the royal house occupies an important role in providing judgment for people coming to the city. As James L. Mays can highlight:

Pilgrimage season was likely a time when conflicts and disputes unsettled in the country courts were brought to the royal officials and their successors in the postexilic period. The peace of the community depended on the establishment of justice. Pilgrimage is a journey in search of justice. (Mays, 1994, p. 393)

The house of David has a crucial role in making Jerusalem a place of shalom, but the psalm also places the house of the LORD as the bookends structurally of the psalm. The place of the house of the LORD at the beginning and end encompasses the authority of the house of David. (NIB IV: 1184) 2 Samuel 7 makes a similar point when the LORD informs David that he will build a house (lineage) for David rather than David building a house for the LORD.

The psalm begins with a joyous embrace of the traditional call to go up to the house of the LORD. There is some debate about whether the perspective of the psalmist is currently in Jerusalem (are) or whether it should be translated in past tense as the psalmist remembers Jerusalem in anticipation of a journey, but I have stayed with the NRSVue’s translation of Our feet are standing. From the perspective of the pilgrim, Jerusalem is a city bound firmly together. There is some Hebrew word play in the word for bound (Hebrew habar) which is never elsewhere used for construction and always refers to human alliances or covenants. (NIB IV:1184) The psalm imagines a time where the unified tribes of Israel gather in Jerusalem as a place of festival, worship, and ultimately peace making.

The language in verse six to seven centers around shalom (peace) and Jerusalem (yeru-shalom) and the structure in Hebrew makes this even clearer by the phonetic repetition of ‘sh’ and ‘l’ sounds. As Nancy deClaissé-Walford states:

Of the ten Hebrew words that make up vv. 6 and 7, six contain the letters sin and lamed: ask (sha’alu); well-being (twice) (shalom); Jerusalem (yerushalaim); may they be at ease (yishelayu); and tranquility (shalwa)—acoustically and visually emphasizing the theme of well-being. (Nancy deClaisse-Walford, 2014, p. 901)

Jerusalem is the city of shalom, the longed-for peace absent in Psalm 120. Peace is for the city of peace, for the walls that defend the city from hostility, and for the families who are present in the city or back home. Psalm 133 will later echo this hope for peace among relatives.

Walter Brueggemann and William H. Bellinger make an important point for this prophetic imagination of the people in the context of the exile. When there is no longer a city of shalom to seek where the houses of the LORD and David reside, how are the people to function? Brueggemann points to the prophet Jeremiah (Jeremiah 29: 4-10) when he states:

”seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you in exile, and pray to the LORD on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare.” The word “welfare” of course renders the Hebrew shalom; the prophet is exhorting the deportees to pray for the shalom of the city of Babylon. (Bellinger, 2014, p. 530)

In the absence of the city, the temple, and the Davidic king it was still possible to seek peace, but it involved seeking the shalom of the place where you find yourself transplanted. Even if Jerusalem is de-centered from the world, peace can still be found in the cities where the pilgrims sojourn.