Matthew 20: 1-16

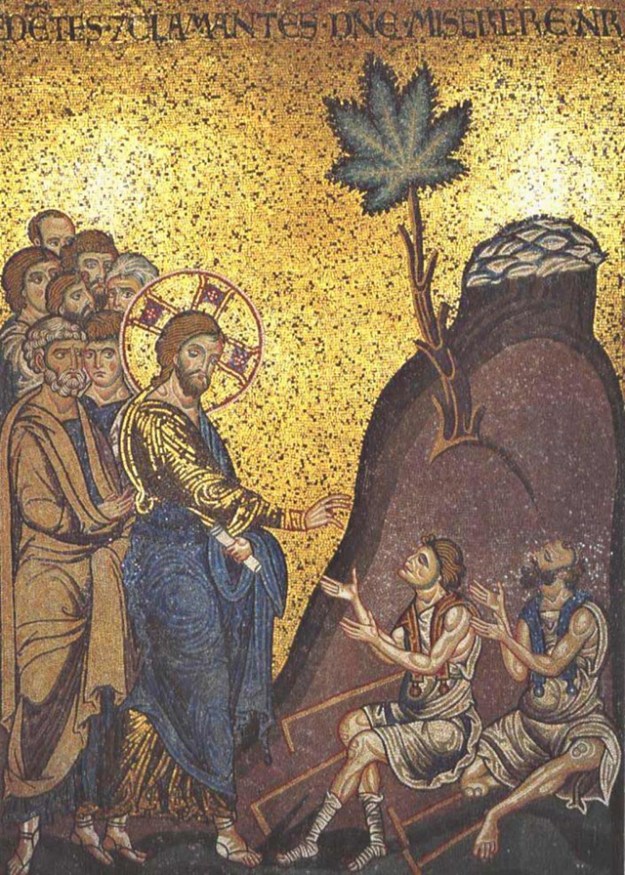

“For the kingdom of heaven is like a landowner who went out early in the morning to hire laborers for his vineyard. 2 After agreeing with the laborers for the usual daily wage, he sent them into his vineyard. 3 When he went out about nine o’clock, he saw others standing idle in the marketplace; 4 and he said to them, ‘You also go into the vineyard, and I will pay you whatever is right.’ So they went. 5 When he went out again about noon and about three o’clock, he did the same. 6 And about five o’clock he went out and found others standing around; and he said to them, ‘Why are you standing here idle all day?’ 7 They said to him, ‘Because no one has hired us.’ He said to them, ‘You also go into the vineyard.’ 8 When evening came, the owner of the vineyard said to his manager, ‘Call the laborers and give them their pay, beginning with the last and then going to the first.’ 9 When those hired about five o’clock came, each of them received the usual daily wage. 10 Now when the first came, they thought they would receive more; but each of them also received the usual daily wage. 11 And when they received it, they grumbled against the landowner, 12 saying, ‘These last worked only one hour, and you have made them equal to us who have borne the burden of the day and the scorching heat.’ 13 But he replied to one of them, ‘Friend, I am doing you no wrong; did you not agree with me for the usual daily wage? 14 Take what belongs to you and go; I choose to give to this last the same as I give to you. 15 Am I not allowed to do what I choose with what belongs to me? Or are you envious because I am generous?’ 16 So the last will be first, and the first will be last.”

This parable, which is unique to Matthew’s gospel, expands on Jesus’ paradoxical proverb about many who are first being last and the last being first. In Matthew, this parable is the final parable prior to entering Jerusalem and is preceded by the parable of the lost sheep and the unforgiving servant in Matthew 18. The world imagined in the parable is jarring for those committed to the capitalistic worldview of our time or the worldview of the nations in Jesus’ time. Each of the three parables in Matthew 18-20 are told specifically in answer to the disciples’ questions about greatness or forgiveness and unlike earlier parables are not explained by Jesus. We are invited not only into the worldview of the disciples of Jesus, but into these short stories which are designed to challenge their assumptions as they begin to embody a different kind of society amidst the nations.

I am making several translational choices that make the story less readable to a casual modern reader but highlight some of the different assumptions and values of the world Jesus spoke to. Our imagination around land and time are different than the ancient world, especially for those who dwell in cities and whose primary place of income is a workplace that is no longer connected with agriculture. For most of history the home was the primary place where economics occurred, and the ‘house master’ was responsible for the stewardship of the economics of their land. What many translations render as a ‘landowner’ is the Greek oikodespotes (oikos- home, this is the word at the root of the modern idea of economy and economics and despot-where our modern word despot comes from, meaning ruler, lord or master) I am rendering more literally as ‘house master.’ Jesus has been referred to himself a ‘house master in 10:25 when he states, “If they have called the master of the house (oikodespotes) Beelzebul, how much more will they malign those of his household.” This term will also appear in Matthew 24:43 in the context of Jesus warning his disciples to stay awake like a house master who does not know when a thief is coming.

While the house master is responsible for both household and land, this does not indicate that the house master will be wealthy or elitist. We may think in modern terms of a person with land and property as the master of an estate with servants to do their bidding, and while that might be the case of this house master we need not assume that it is the case. We only hear of one person who works directly for the house master in this parable, and while many interpreters assume that the house master is wealthy and going into the marketplace to hire workers would be below him, that is an assumption that the house master oversees a large household with many servants or slaves that work for him. It is worth remembering that a part of the Jewish hope is for everyone is to live securely in their own land. Whether 1 Kings 4: 25 is accurate that under Solomon everyone had their own vine and fig tree, the prophetic hope resonates with this image:

But they shall all sit under their own vines and under their own fig trees, and no one shall make them afraid; for the mouth of the LORD has spoken. Micah 4:4, see also Zechariah 3: 10

Regardless of the whether the house master is wealthy or merely owns a vineyard, we will see in the parable that this individual acts in a way that is very unusual in the disciples’ worldview and in ours.

In the modern western culture we imagine time in the way we measure it on a clock, watch or cell phone with the day broken into precise hours, minutes and seconds, and while many work hours outside of the eight hour, 9 a.m.-5 p.m. we often think of the forty hour week as a standard for work. The workday in the ancient world is constructed around daylight hours, and here in the world of this parable we have an approximately twelve-hour workday. The house master goes out during the fourth watch (before dawn) into the marketplace to find workers, and while some translations smooth the agreed upon wage to ‘the usual daily wage’ I believe most readers can understand the agreement for a concrete price, a denarius, even if they may not be able to precisely fix the value of this payment in modern equivalents. The agreement for a specific payment by both the house master and the workers is important to this story. To render the times when the house master returns to the market place as nine o’clock, noon, three o’clock and five o’clock assumes our precise relationship with time and can give the illusion of something resembling our normal workday, the more literal third hour, sixth hour, ninth hour, and the eleventh hour, reminds us that the workday is long and it may remind us that time was not measured by clocks, but by the movement of the sun.

A vineyard, unlike grain crops sown in a field, require constant tending. Most commentators assume that the house master has gone to bring in workers for the harvest, but that may not be the assumption of those in Jesus’ time hearing this parable. The reality that there are workers throughout the day who are without work (most English translations place a value judgment on their translations on the laborers when they state they are ‘standing idle’ but the Greek agroi literally means without work) the laborers answer that no one was hiring along with the quick agreement on a wage may indicate a time where the supply of workers exceeded demand. Also, as Amy Jill-Levine notes, “The householder continues to go to the market, but the parable makes no explicit mention of the need for more labor.” (Levine 2014, 226) Perhaps, something very strange is happening with this house master who continues to bring more workers into their vineyard to work. The harvest may indeed be great, or the house master may indeed be generous.

Sometimes this parable is quickly allegorized to talk about grace and ‘salvation’ or the assumption is made that those who are in the vineyard early are the Pharisees and/or Sadducees but reading the context of the story I want to suggest two different frames for this story. All of the parables in Matthew 18-20 are in response to the questions of the disciples, and this parable follows Peter’s question, “What then will we have?” so likely Matthew is not concerned with groups outside the followers of Jesus, but precisely the imagination and actions of those whom Jesus has called from the fishing boats, marketplace or wherever they have come from to follow him. But it is also helpful to remember that Jesus is using a commonly used image for Israel, the vineyard (see Isaiah 5, Jeremiah 7) to tell a very Jewish parable. Christians may be conditioned to continually question ‘what thing we might do to have eternal life’ (see my discussion of this question in the previous section) but rather than spiritualizing the parable to concern the afterlife, what if it is concerned with how members of the kingdom of heaven relate to one another. As Dr. Levine can again state insightfully, “To those who ask today, “Are we saved?” Jesus might well respond, “The better questions is, ‘Do your children have enough to eat?’ of ‘Do you have a shelter for the night?’” (Levine 2014, 216)

I am going against the grain assuming that the ‘house master’ is good, since many would side with the workers in the parable around issues of fairness or justice. When the parable is spiritualized to be about the afterlife is removes the scandal from the parable, but it also misses the fruit that is hanging from the vines to be gathered. When the house master orders his steward to pay the workers at the end of the day he is acting in accordance with the expectations of the law (Lev. 19: 13, Deut. 24: 14-15) and Deuteronomy 24: 15 is particularly worth noting in this context:

You shall pay them (poor and needy laborers) daily before sunset, because they are poor and their livelihood depends on them; otherwise they might cry to the LORD against you and you would incur guilt.

In our capitalistic worldview a person who works longer should receive a better payment, and the first should not be treated as equal with those who came last but should receive better compensation for more time spent in labor. When the lord (and the Greek here is kurios which is normally translated lord) of the vineyard calls his steward to distribute payment beginning with the last and going to the first we receive a verbal cue that something is about to be turned upside down. Those who the house master sent into the vineyard at the eleventh hour receive a denarius setting up the expectations of earlier workers and the listeners of a greater reward for those present from early morning. Yet, there is something different in this house master who acts according to the vision of the kingdom of heaven, and who can claim to be good (this is the Greek agathos which is translated good twice in the previous story and the translation of generous in many translations obscures the linkage with the character of God, see previous section) This parable invites us into a world where the lord of the vineyard, which is now closely linked to the LORD the God of Israel (who is good) models a world where a house master goes continually in the marketplace looking for workers to ensure they have work that pays in a timely manner and ensures that children have enough to eat and workers can find shelter for the night. Perhaps this kingdom of heaven is about a world where all the laborers can have enough to eat, and God provides sufficiently for all instead of a world where laborers are only satisfied in the afterlife. When we hear a person address another as ‘friend’ we may assume intimacy, but in Matthew’s gospel the term ‘friend’ is used in a setting of formality when another has acted improperly. (see also 22:12, 26: 50) What is smoothly translated ‘are you envious’ is the phrase ‘or is the eye of you wicked/evil’ and the ‘evil eye’ in ancient cultures was to curse or wish harm on another, but here the house master declares that this action, which in opposition to the good, is uncalled for. In the values of the kingdom of heaven, where the last are first and the first are last, the master of the house goes out to ensure that as many workers as possible receive the opportunity to work, to provide for their families, and to have shelter for the night. Until a time when all can rest under their own vines and fig trees the house master works to provide out of their goodness for the laborers in the marketplace.

We live in a society that is very defensive of its individualistic and capitalistic values and is quick to label things that value the needs of the society above the individual or the workers above profit as socialist, communist, or Marxist. Ultimately the values that Jesus points to are older than either capitalism or Marxism, or the individualism that evolved from the Enlightenment. Jesus’ vision of the kingdom of heaven conflicts with all of the ways we are used to framing our identity in our post-Enlightenment, modern (or postmodern) secular age. It does not fit neatly into our labels and titles but instead invites our imaginations into a new way of viewing our world, our society, and our neighbors. Although Jesus does point to a reality beyond this world, his teaching and parables are mainly concerned with how we live in relation to others within life. Jesus’ suggestion of a house master who provides out of his goodness for the laborers in the marketplace conflicts with our ideas of fairness. Yet, the richness of these short narratives that Jesus tells is the way they poetically challenge our imaginations to conceive of the world in a new way, with a different set of principles and visions. Disciples who look at the world hierarchically have to be reoriented to a world where the last are first and the first are last. Disciples, ancient and modern, have struggled with their inability to embrace the world imagined in the kingdom of heaven.