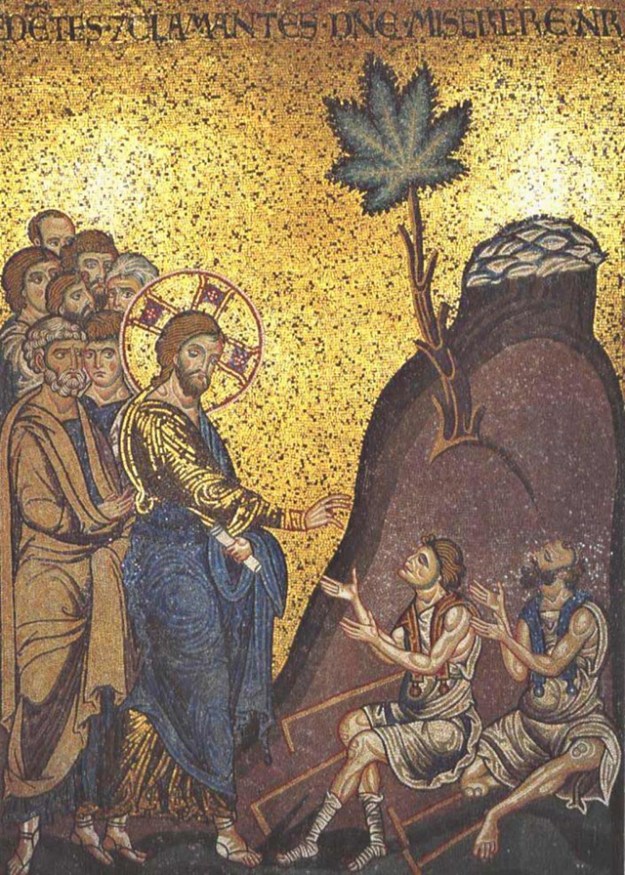

James Tissot, The Blind in the Ditch (1886-1894)

Matthew 15: 1-20

Parallel Mark 7: 1-23; Luke 11: 37-41; 6: 39

Then Pharisees and scribes came to Jesus from Jerusalem and said, 2 “Why do your disciples break the tradition of the elders? For they do not wash their hands before they eat.” 3 He answered them, “And why do you break the commandment of God for the sake of your tradition? 4 For God said, ‘Honor your father and your mother,’ and, ‘Whoever speaks evil of father or mother must surely die.’ 5 But you say that whoever tells father or mother, ‘Whatever support you might have had from me is given to God,’ then that person need not honor the father. 6 So, for the sake of your tradition, you make void the word of God. 7 You hypocrites! Isaiah prophesied rightly about you when he said:

8 ‘This people honors me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me; 9 in vain do they worship me, teaching human precepts as doctrines.'”

10 Then he called the crowd to him and said to them, “Listen and understand: 11 it is not what goes into the mouth that defiles a person, but it is what comes out of the mouth that defiles.” 12 Then the disciples approached and said to him, “Do you know that the Pharisees took offense when they heard what you said?” 13 He answered, “Every plant that my heavenly Father has not planted will be uprooted. 14 Let them alone; they are blind guides of the blind. And if one blind person guides another, both will fall into a pit.” 15 But Peter said to him, “Explain this parable to us.” 16 Then he said, “Are you also still without understanding? 17 Do you not see that whatever goes into the mouth enters the stomach, and goes out into the sewer? 18 But what comes out of the mouth proceeds from the heart, and this is what defiles. 19 For out of the heart come evil intentions, murder, adultery, fornication, theft, false witness, slander. 20 These are what defile a person, but to eat with unwashed hands does not defile.”

Jesus and the Pharisees and scribes, as presented here, have different points of reference as they enter this argument. The Pharisees in the gospel have had a growing list of complaints about the practices of Jesus and his disciples: they eat with the wrong people (9:11), they do not fast (9:14), they pluck grain on Sabbath when they are hungry (12:2), Jesus heals on Sabbath (12:10), in our current passage they don’t wash their hands before eating and in future readings will come questions of paying taxes to the Temple (17:24) and the emperor (22:17) (Case-Winters, 2015, p. 197) All of these visible practices which are not wrong or evil and may even be life giving in the right context (I’m writing on this passage on washing hands before eating in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic) also become ways of judging the righteousness of others or practicing one’s piety before others. These conflicts resonate strongly with Jesus’ words in the Sermon on the Mount which I will discuss below, but also highlight the difference between piety and righteousness.

The Pharisees and scribes that come to engage Jesus’ practices now come from Jerusalem, and this is the first time we have indication, since the very beginning of Jesus’ ministry when great crowds from Galilee, the Decapolis, Judea, Jerusalem and beyond the Jordan came to Jesus, (4:25) that Judea and Jerusalem and their authorities are aware of Jesus’ ministry predominantly in Galilee. Jesus’ practices, or at least the practices of his disciples in this instance, do not fit within the frame of what holiness practiced by visible actions that demonstrate one’s faithfulness, one’s piety, according to the practices of these Pharisees and scribes. There is a lack of openness to the works that Jesus is doing because they do not fit within the expectations of these leaders who have come to challenge the worker of the acts of power and the teacher of a different understanding of the relationship between the law and the tradition.

Jesus has very little interest in piety, and this is one of the reasons that most English translations of Matthew 6 of dikaisune as piety instead of righteousness misunderstand what Jesus is attempting to state. Jesus in Matthew 6: 1 stated, “Beware of practicing your righteousness (not piety) before others in order to be seen by them;” because the very practices that Jesus is being judged for here are the things that fail to produce changed hearts. Pietas (often translated piety from Latin) was an important Roman concept which the orator and statesman Cicero describes as that, “which admonishes us to do our duty to our country or our parents or other blood relations.” Jesus’ understanding of righteousness is not limited to ‘doing one’s duty’, particularly as it is viewed by others. Central to the language of the Sermon on the Mount were these practices of righteousness done in a way not to call attention to the individual’s practices. The actions of the community of the faithful may be visible, but the individual practices of the disciple will not be. Jesus may not look like he and his disciples are ‘doing their duty’ as viewed by the Pharisees but Jesus does not view them as faithful guides for how a community should practice righteousness.

The practice of washing hands comes from places in the law like Exodus 30: 19-21 (priests washing before entering the tent of meeting), Leviticus 15: 11 (washing after a bodily discharge) and Deuteronomy 21: 6 (where washing absolves the leaders of a community of responsibility an unsolved murder). The tradition of the elders mentioned here would be an expansion of the practices outlined in the law which only become troubling when they become standards for judging the holiness or acceptability of others. Jesus’ response goes directly back to the commandment and the justifications, often religious, that people might use to not fulfill their covenant responsibility to others. As I mentioned in the discussion of the commandment on honoring parents in both Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5, this commandment is not primarily about young children being obedient to parents but instead older children continuing to honor, respect, and care for elderly relatives. If this practice of dedicating wealth and property to the temple or to the priests in order to abandon one’s responsibility to a family member occurred, it would be masking unrighteousness in the appearance of socially respectable piety.

Jesus may bring about divisions in families and may call his followers to ‘let the dead bury their own dead’ or declare those who do the will of his Father in heaven are his ‘brother and sister and mother.’ But it is important for Matthew to continue to link Jesus as the fulfillment of the intent of the law. Jesus never declares that families do not have value and that family connections are not to be honored; they are simply not ultimate. The Pharisees who would practice this ‘dedication of one’s resources to God’ through the temple or the Pharisees, in lieu of caring for family probably felt they were making the same argument. Eyes opened to faith can see what is at the center of practicing righteousness and how faithfulness to Jesus takes a higher place than loyalty to temple or a religious community. The inability to distinguish between piety and righteousness leaves these Pharisees and scribes as blind guides leading the blind.

Hypocrites is a word that Matthew uses more than the rest of scripture, but its use here connects us both with its usage in the Sermon on the Mount (6:2, 6:5. 6:16, 7:5) and Matthew’s frequent use of the term in the conflicts with the Pharisees in Jerusalem (22:18; 23: 13, 15, 23, 25, 27, 29; 24: 51). As I mentioned when discussing 7:5, when righteousness becomes reduced to piety to demonstrate our own faithfulness or righteousness, we become like the one blind to the log in their own eye while trying to remove the splinter from another’s eye. Our expectations of what piety should look like allow us to pre-judge (where the term prejudice comes from) others and may make us blind to the ways our own practices may lead others astray.

Jesus, like the prophets before him, continually had to remind people that religious practices were not enough. Anna Case-Winters, picking up on the language of the Isaiah quotation, cleverly calls attention to reality that ‘lip-service” is not enough. A heart oriented on God and the way of life God calls God’s people to live is far more central and allows the right intentions to flow out of the mouth and to proceed from one’s hands (washed or unwashed). The Pharisees are scandalized (took offense, NRSV) according to the disciples but Jesus remains unconcerned by their judgments. He views them similarly to the weeds sewn among the wheat (13: 24-30) and as those who in their blindness are leading others in blindness. Like the Pharisees in John 9 who cannot accept the blind man who can now see and become spiritually blind, these Pharisees remain unable to see and participate with the reality of the Kingdom of Heaven’s work and presence in Jesus. Their prejudgment of Jesus makes them unable to properly see the road they are walking down which leads them and others who follow them into a pit.

The Pharisees are not the only ones who have trouble seeing and understanding what Jesus is saying, even the disciples have to ask for clarification. Peter, on behalf of the other disciples presumably, asks for clarification and Jesus explains that it is not what goes into a person, but what comes out of a person that defiles. A clean heart is more important than washed hands, and the actions which destroy community cause far greater harm than the practices of how or what one eats. Yet, Matthew also does not include Mark’s note in the parallel story that “Thus he declared all foods clean.” (Mark 7:19b) Matthew does not discard all the practices that the Jewish people practiced, and many in Matthew’s community may have refrained from eating foods traditionally declared unclean like pork or shellfish. But Matthew also does not allow these practices to give the disciples permission to prejudge others who practice their righteousness in a different way. There will be surprisingly faithful ones among those who were once considered Gentile dogs.

Maybe instead of being the weed no one wants in the field maybe the mustard seed is that which gives rise to a plant which once it emerges grows prodigiously producing with both curative and flavor producing properties meant to be shared among the creation of God, both birds of the air and the people of the earth. Perhaps, like the trees on either side of the river of life in Revelation 22, this small seed emerges as something for feeding creation and healing the nations. Perhaps this is part of the reason faith the size of a mustard seed can move mountains for little faith ones (Matthew 17: 20)

Maybe instead of being the weed no one wants in the field maybe the mustard seed is that which gives rise to a plant which once it emerges grows prodigiously producing with both curative and flavor producing properties meant to be shared among the creation of God, both birds of the air and the people of the earth. Perhaps, like the trees on either side of the river of life in Revelation 22, this small seed emerges as something for feeding creation and healing the nations. Perhaps this is part of the reason faith the size of a mustard seed can move mountains for little faith ones (Matthew 17: 20)