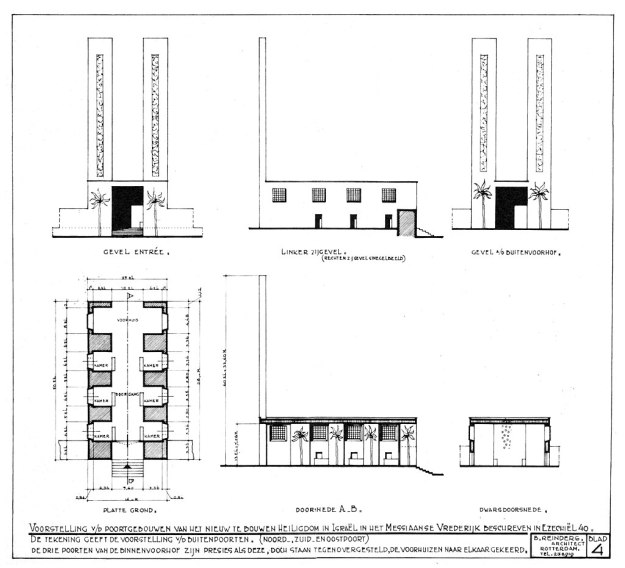

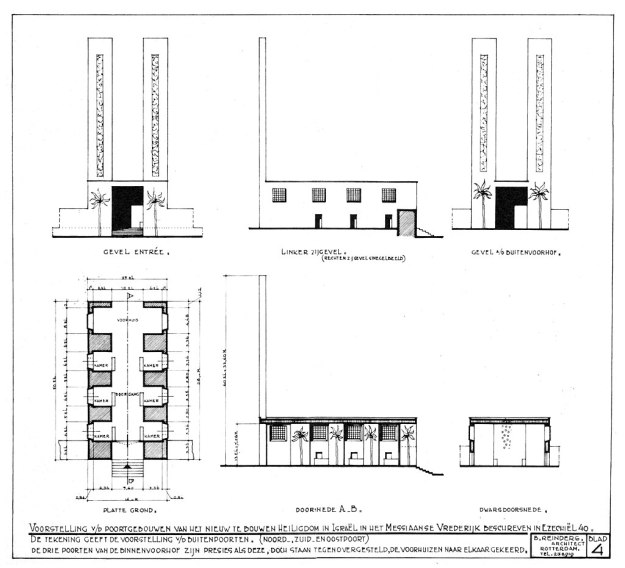

Schematic of Ezekiel’s Temple drawn by Dutch architect Bartelmeüs Reinders, Sr. (1893–1979) released into public domain by artist.

Ezekiel 40:1-4 Beginning the Final Vision

1 In the twenty-fifth year of our exile, at the beginning of the year, on the tenth day of the month, in the fourteenth year after the city was struck down, on that very day, the hand of the LORD was upon me, and he brought me there. 2 He brought me, in visions of God, to the land of Israel, and set me down upon a very high mountain, on which was a structure like a city to the south. 3 When he brought me there, a man was there, whose appearance shone like bronze, with a linen cord and a measuring reed in his hand; and he was standing in the gateway. 4 The man said to me, “Mortal, look closely and listen attentively, and set your mind upon all that I shall show you, for you were brought here in order that I might show it to you; declare all that you see to the house of Israel.”

When looking at ancient manuscripts you can often tell what was important to the author and the community that continued to transmit the author’s work by the amount of space dedicated to the subject. In a world before printers and copiers where words were copied by hand it is clear that the description of sacred spaces is extremely important in the life of the community. Although it is not the last vision of Ezekiel by date[1] its position at the end of Ezekiel’s collected words is significant. It is also much longer than any of Ezekiel’s other visions. In a time of great disorder this vision of hope points to a perfectly ordered future.

This vision is given two reference points, the beginning of Ezekiel’s exile and the Destruction.[2] This is the only vision dated from the destruction of Jerusalem, and it is fourteen years after the remnant of Jerusalem and Judah arrived in exile in Babylon. Now as the nation is becoming accustomed to life in exile there emerges a vision of a new possibility beyond exile. In the disorienting reality of life as strangers in a strange land the prophet, in Katheryn Pfisterer Darr’s words,

describes a perfectly ordered homeland under the leadership of a perfectly ordered homeland under the leadership of a perfectly ordered priesthood serving in a perfectly ordered Temple complex. (NIB VI:1532)

The date of the vision, the tenth day of the first month, would coincide with the Passover celebration:

This month shall mark for you the beginning of months; it shall be the first month of the year for you. Tell the whole congregation of Israel that on the tenth of this month they are to take a lamb for each family, a lamb for each household. Exodus 12: 2-3

But as the people resided in Babylon it would also occur during the Babylonian akitu festival which celebrated the enthronement of Marduk. The religion of the conquerors may have been a powerful draw to many of the Judeans who felt their God had abandoned them. The danger of settling in the land of Babylon was adopting the practices and worship of their neighbors. Here the dual setting of the worship of Marduk and the promise of liberation by the God of Israel form a dramatic tension.

This final vision of Ezekiel has numerous parallels to the Torah attributed to Moses to order the society in their journey from slavery to becoming the people of God. Both the tabernacle and the temple were expected to be places where God’s presence could dwell among the people. Previously in chapter eight, the desecration of the previous temple was revealed, and now that temple lies in ruins and God’s presence abandoned that structure.[3] This new and perfectly ordered temple guarded from the abominable practices which cause the LORD’s fury once again provides a hope for God’s presence in the midst of the people.

The man, whose appearance shines like bronze or copper, is obviously an individual from the divine rather than the human realm. This unusual man functions both like the guide in chapter eight, but also is outfitted as a surveyor. Ezekiel now takes on the role of a recorder of measurements for this orderly structure at the center of a reordered world. Briefly mentioned is ‘a city to the south’ but this note is echoed at the end of the vision where the city is named Yahweh Shammah (Yahweh is there). This vision is to be recorded and communicated to the people of Israel, a vision of hope in a hopeless time, a vision of order in disorder, a new future from shattered past. The new beginning begins with a new sacred space.

Ezekiel 40: 5-16 The Wall and Outer Gate

5 Now there was a wall all around the outside of the temple area. The length of the measuring reed in the man’s hand was six long cubits, each being a cubit and a handbreadth in length; so he measured the thickness of the wall, one reed; and the height, one reed. 6 Then he went into the gateway facing east, going up its steps, and measured the threshold of the gate, one reed deep. There were 7 recesses, and each recess was one reed wide and one reed deep; and the space between the recesses, five cubits; and the threshold of the gate by the vestibule of the gate at the inner end was one reed deep. 8 Then he measured the inner vestibule of the gateway, one cubit. 9 Then he measured the vestibule of the gateway, eight cubits; and its pilasters, two cubits; and the vestibule of the gate was at the inner end. 10 There were three recesses on either side of the east gate; the three were of the same size; and the pilasters on either side were of the same size. 11 Then he measured the width of the opening of the gateway, ten cubits; and the width of the gateway, thirteen cubits. 12 There was a barrier before the recesses, one cubit on either side; and the recesses were six cubits on either side. 13 Then he measured the gate from the back of the one recess to the back of the other, a width of twenty-five cubits, from wall to wall. 14 He measured also the vestibule, twenty cubits; and the gate next to the pilaster on every side of the court. 15 From the front of the gate at the entrance to the end of the inner vestibule of the gate was fifty cubits. 16 The recesses and their pilasters had windows, with shutters on the inside of the gateway all around, and the vestibules also had windows on the inside all around; and on the pilasters were palm trees.

Most modern readers will look at the description of the structure and either be overwhelmed by the description or those with engineering or construction backgrounds will be perplexed by the missing details that would be required to construct the temple. In a world where literacy was relatively rare and copying a document was a labor, resource, and time intensive process.[4] Yet, like the previous descriptions of the tabernacle and temple, there is nowhere near enough information to actually construct the temple Ezekiel is shown. Tova Ganzel speculates that the “opacity of the verses and the futility of trying to base the construction on them is deliberate” to prevent anyone from attempting to carry out the temple construction at any point in the future. (Ganzel, 2020, p. 361) At the same time it is important for the prophet to convey a vision of the temple that the people can envision to give specificity to this image of hope.

Gateways of Ezekiel’s Temple, as described in the Book of Ezekiel, drawn by the Dutch architect Bartelmeüs Reinders (1893–1979) released into public domain by artist.

The temple is oriented to the east, and this is a common practice across religions in temple construction (the temple faces towards the direction of the rising sun). It is surrounded by a ten-foot tall and ten-foot thick wall. The temple is walled off from the surrounding world and even the city to the south and much of the external structure is similar to what is expected in walled cities rather than temples. This eastern gate is a large structure, the gate opens to be roughly seventeen feet in width, but the gateway itself is about twenty-two feet wide. The width of the gate is later stated to be twenty-five feet. When you add the length of the gateways vestibules, pilasters which lead from the outside of the temple into the inner courtyard it is fifty cubits, or roughly eighty-six feet. Like ancient, fortified cities, the vestibules and ‘windows’[5] may be for defensive purposes.

This temple is created to be a place where God can dwell among the people in a reestablished relationship, and the creation of the temple is the setting aside of a holy space. In creating this holy space there is a need to separate it from the mundane space surrounding the temple, and this exterior wall forms an initial and likely guarded barrier between the people and God’s space at the center of the temple. Most Christian worship spaces have significantly reduced the space between the people and God, but for our Jewish ancestors this separation was essential. God was holy, the people were not. To defile God’s holy place was to invite God to abandon the people or to lash out at the defilement, as we have seen throughout Ezekiel. Now a new beginning begins with a new structure walled off and protected from the outside world’s interference.

Ezekiel 40: 17-27 The Outer Court

17 Then he brought me into the outer court; there were chambers there, and a pavement, all around the court; thirty chambers fronted on the pavement. 18 The pavement ran along the side of the gates, corresponding to the length of the gates; this was the lower pavement. 19 Then he measured the distance from the inner front of the lower gate to the outer front of the inner court, one hundred cubits.

20 Then he measured the gate of the outer court that faced north — its depth and width. 21 Its recesses, three on either side, and its pilasters and its vestibule were of the same size as those of the first gate; its depth was fifty cubits, and its width twenty-five cubits. 22 Its windows, its vestibule, and its palm trees were of the same size as those of the gate that faced toward the east. Seven steps led up to it; and its vestibule was on the inside. 23 Opposite the gate on the north, as on the east, was a gate to the inner court; he measured from gate to gate, one hundred cubits.

24 Then he led me toward the south, and there was a gate on the south; and he measured its pilasters and its vestibule; they had the same dimensions as the others. 25 There were windows all around in it and in its vestibule, like the windows of the others; its depth was fifty cubits, and its width twenty-five cubits. 26 There were seven steps leading up to it; its vestibule was on the inside. It had palm trees on its pilasters, one on either side. 27 There was a gate on the south of the inner court; and he measured from gate to gate toward the south, one hundred cubits.

There are two additional outer gates that lead into the courtyard, one facing north and one facing south, of identical description to the eastern gate. There is no western gate, since the inner court of the structure is at the western edge of the complex and separated by the court and the wall from the surrounding people. As the temple sections become closer to the space where God’s presence is expected the elevation increases. The architecture ascending reflects the increasing holiness of this space and the closer proximity to the divine. The thirty chambers which surround the outer court are not given any specific function here, but Jeremiah 35: 2-4 suggests that they were places for meeting, eating and drinking, and Nehemiah 13: 4-14 indicates they were to be used for storage of grain offerings, frankincense, and tithes of grain, wine, and oil.[6] Once a person passed the outer gates there was a separation of one hundred cubits (roughly one hundred seventy feet) from the outer gates to the inner gates.

Ezekiel 40: 28-47 The Inner Court

28 Then he brought me to the inner court by the south gate, and he measured the south gate; it was of the same dimensions as the others. 29 Its recesses, its pilasters, and its vestibule were of the same size as the others; and there were windows all around in it and in its vestibule; its depth was fifty cubits, and its width twenty-five cubits. 30 There were vestibules all around, twenty-five cubits deep and five cubits wide. 31 Its vestibule faced the outer court, and palm trees were on its pilasters, and its stairway had eight steps.

32 Then he brought me to the inner court on the east side, and he measured the gate; it was of the same size as the others. 33 Its recesses, its pilasters, and its vestibule were of the same dimensions as the others; and there were windows all around in it and in its vestibule; its depth was fifty cubits, and its width twenty-five cubits. 34 Its vestibule faced the outer court, and it had palm trees on its pilasters, on either side; and its stairway had eight steps.

35 Then he brought me to the north gate, and he measured it; it had the same dimensions as the others. 36 Its recesses, its pilasters, and its vestibule were of the same size as the others; and it had windows all around. Its depth was fifty cubits, and its width twenty-five cubits. 37 Its vestibule faced the outer court, and it had palm trees on its pilasters, on either side; and its stairway had eight steps.

38 There was a chamber with its door in the vestibule of the gate, where the burnt offering was to be washed. 39 And in the vestibule of the gate were two tables on either side, on which the burnt offering and the sin offering and the guilt offering were to be slaughtered. 40 On the outside of the vestibule at the entrance of the north gate were two tables; and on the other side of the vestibule of the gate were two tables. 41 Four tables were on the inside, and four tables on the outside of the side of the gate, eight tables, on which the sacrifices were to be slaughtered. 42 There were also four tables of hewn stone for the burnt offering, a cubit and a half long, and one cubit and a half wide, and one cubit high, on which the instruments were to be laid with which the burnt offerings and the sacrifices were slaughtered. 43 There were pegs, one handbreadth long, fastened all around the inside. And on the tables the flesh of the offering was to be laid.

44 On the outside of the inner gateway there were chambers for the singers in the inner court, one at the side of the north gate facing south, the other at the side of the east gate facing north. 45 He said to me, “This chamber that faces south is for the priests who have charge of the temple, 46 and the chamber that faces north is for the priests who have charge of the altar; these are the descendants of Zadok, who alone among the descendants of Levi may come near to the LORD to minister to him.” 47 He measured the court, one hundred cubits deep, and one hundred cubits wide, a square; and the altar was in front of the temple.

As Ezekiel is led further into the heart of the temple he continues to pass through large gates and ascends an additional eight stairs increasing the elevation of the inner court. The gateways into the inner court are also twenty-five by fifty cubits, the same dimensions as the outer gateways. These gateways separate the outer courtyard from the inner courtyard and presumably restrict access to only those set apart for the ministry in the temple. The temple’s function is to bring offerings to God, rather than a place of gathering like most modern worship spaces. In this gateway to the inner courtyard is a room for the preparation and offering of sacrifices. The description of the tables and pegs is functional and a person of priestly heritage, like Ezekiel, probably would be familiar with the proper layout of the temple, the proper preparation of offerings, and the utilization of this space.

The priests who have ‘charge’ of the temple and the altar are likely charged with guarding these spaces for their proper use by the proper people. The Hebrew word samar behind the English ‘charge’ is normally used in relation to guard duty or keeping watch over something in order to protect it. In chapter eight we saw the defilement of the temple by the elders of Judah, and now these priests are charged to ensure that the temple, particularly the inner court, remains a holy space undefiled by improper worship or idolatrous figures.

Ezekiel 40: 48-49 Entering the Temple

48 Then he brought me to the vestibule of the temple and measured the pilasters of the vestibule, five cubits on either side; and the width of the gate was fourteen cubits; and the sidewalls of the gate were three cubits on either side. 49 The depth of the vestibule was twenty cubits, and the width twelve cubits; ten steps led up to it; and there were pillars beside the pilasters on either side.

Although these final two verses of the chapter would fit better with the following chapter which focuses on the temple itself, I will keep with the chapter divisions and comment briefly on the entrance into the temple. Now the gate structure is twenty cubits total, fourteen cubit entry and three cubits on either side. The vestibule (room) is twenty cubits by twelve cubits[7] with an additional ten steps moving us up into a higher space (reflecting architecturally a holier space). In addition to the pilasters (pillars built on the wall) there are two free standing pillars in the entry, probably copying the two bronze pillars, Jachin and Boaz, of Solomon’s temple mentioned in 1 Kings 7: 15-22. Any priest familiar with the design of Solomon’s temple would have noticed these large brass pillars in the past and they were likely a visible reminder of the opulence of the now destroyed temple. This vision of a new temple has not focused on the gold and other resources expended on the construction like 1 Kings, but this original temple likely shaped the imaginations of Ezekiel and his later readers.

[1] Ezekiel’s last by date prophecy begins in Ezekiel 29:17 (April 26, 571 BCE) two years after this date.

[2] The destruction of both Jerusalem and the temple.

[3] Ezekiel 10.

[4] One of my personal practices is hand copying the texts that I am working through (in English) just to accommodate myself to the reality of the transmission of these texts over thousands of years. Scrolls and later codices (ancient books) also would have used vellum, parchment, or papyrus rather than paper. These resources were much more expensive than modern paper. The preservation of a book like Ezekiel, which takes most of a modern 100 sheet composition book to write out, is a significant investment of time and resources in the ancient world.

[5] The ‘windows’ (Hebrew hallonot atumot) are the source of a lot of exegetical speculation. They may be ‘false windows’ with stones set in the relief, (Ganzel, 2020, p. 361) or slotted windows for archers, cupboards for utensils or tools for temple guards. (Block, 1998, p. 522)

[6] The controversy in Nehemiah is when one of these rooms is prepared as a room for Tobiah, which Nehemiah vehemently disapproves of.

[7] Roughly thirty-five feet by twenty-one feet.