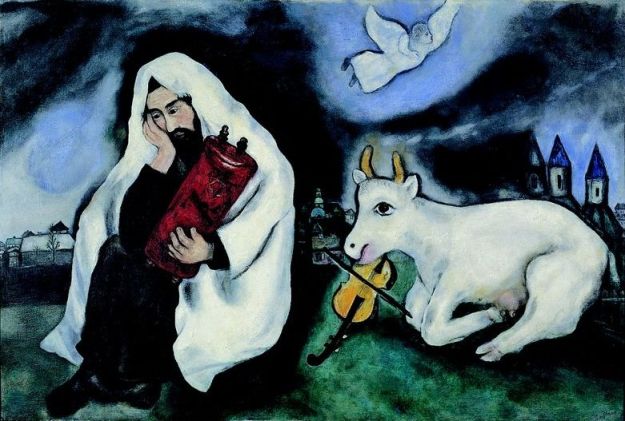

Hezekiah showing off his wealth to envoys of the Babylonian king, oil on canvas by Vicente López Portaña, 1789

2 Kings 20: 1-11

1 In those days Hezekiah became sick and was at the point of death. The prophet Isaiah son of Amoz came to him and said to him, “Thus says the LORD: Set your house in order, for you shall die; you shall not recover.” 2 Then Hezekiah turned his face to the wall and prayed to the LORD, 3 “Remember now, O LORD, I implore you, how I have walked before you in faithfulness with a whole heart and have done what is good in your sight.” Hezekiah wept bitterly. 4 Before Isaiah had gone out of the middle court, the word of the LORD came to him, 5 “Turn back and say to Hezekiah prince of my people: Thus says the LORD, the God of your ancestor David: I have heard your prayer, I have seen your tears; indeed, I will heal you; on the third day you shall go up to the house of the LORD. 6 I will add fifteen years to your life. I will deliver you and this city out of the hand of the king of Assyria; I will defend this city for my own sake and for my servant David’s sake.” 7 Then Isaiah said, “Bring a lump of figs. Let them take it and apply it to the boil, so that he may recover.”

8 Hezekiah said to Isaiah, “What shall be the sign that the LORD will heal me and that I shall go up to the house of the LORD on the third day?” 9 Isaiah said, “This is the sign to you from the LORD, that the LORD will do the thing that he has promised: Shall the shadow advance ten intervals, or shall it retreat ten intervals?” 10 Hezekiah answered, “It is normal for the shadow to lengthen ten intervals; rather, let the shadow retreat ten intervals.” 11 The prophet Isaiah cried to the LORD, and he brought the shadow back the ten intervals, by which the sun had declined on the dial of Ahaz.

Even though these final two stories are placed after the siege of Jerusalem by Assyria they probably occurred earlier in the timeline, and the timeline given within the story indicates this as well. Chapter eighteen indicates that Hezekiah reigned for twenty-nine years, and within this story his life is extended by fifteen years which places these events in the fourteenth year of King Hezekiah’s reign. This is significant because the fourteenth year of his reign (701 BCE) is when Jerusalem is besieged by Assyria (see 2 Kings 18:13) and although the illness and recovery could happen in the immediate aftermath of the siege the indication that “I will deliver you and this city out of the hands of the king of Assyria” probably indicates an impending threat to the city. The recovery of the king and the fate of the city are bound together with King Hezekiah being the model of the faithful king.

This is the fourth story in the narrative of 1&2 Kings where a king has asked the prophet if they will recover. In each of the previous stories: the wife of Jeroboam inquiring of Ahijah about her son (1 Kings 14: 1-18), King Ahaziah (who sends messengers to inquire of Baal-zebub and is given his sentence by Elijah in 2 Kings 1), and Ben-hadad (who the prophet Elisha delivers both the positive message of healing and the prophecy that leads to the kings murder by Hazael in 2 Kings 8: 7-15) the person asking ultimately dies. This fourth story the initial message is that the illness is fatal, and the king should put his affairs in order. King Hezekiah turns away from the prophet and tearfully and prayerfully prays to God.

Hezekiah’s prayer as recorded echoes the language of the prayers of the book of Psalms, where the prayer of the individual lifts up how they have walked in faithfulness and call upon God to respond to their obedience. The prayer of the faithful king changes God’s mind on the future for the king and by extension for the city. Brueggemann when writing about Isaiah’s description[1] of the king’s prayer can write:

The prayer of the king has changed the inclination of Yahweh. Prayer is not simply a subjective act of emotional posturing and submissiveness. It impinges upon God. The divine assurance takes place through four verbs: I have heard, I have seen, I will add, I will deliver…not unlike the series of verbs in Exodus 2:24-25 and 3:7. (Brueggemann, Isaiah 1-39: Westminster Bible Commentary, 1998, pp. 303-304)

The response of the LORD through the prophet Isaiah is rapid, before the prophet leaves the palace grounds, and the king is promised restoration within three days and an additional fifteen years of life. The king asks for a sign and Isaiah offers that the LORD can move the sun to alter the time on a sundial, where the LORD will ultimately move the sundial back ten intervals. Unlike his father King Ahaz who was offered a sign by Isaiah and refused it (Isaiah 7) King Hezekiah asks for a sign, and it is granted. There are some similarities to the requests of Joshua request for more daylight in his battle against the Amorites (Joshua 10: 1-15) or Gideon’s request for a sign with the fleece (Judges 6:36-40), and in each story the LORD is not offended by the request for the sign and indeed grants it.

Hezekiah’s boil is treated with a poultice of figs, and although we do not know the nature of Hezekiah’s disease, the treatment and the promise of God work together to affect the healing of the king and to enable him to reign for an additional fifteen years. Unlike King Azariah (aka Uzziah) whose leprosy prevented him from continuing to reign (2 Kings 15:5), Hezekiah’s time as king is doubled by God’s intervention in response to the king’s tears and prayers. Although the editor of 2 Kings, like Isaiah and Chronicles, probably wanted to place the story of Jerusalem’s survival as the focal event of King Hezekiah’s reign, this story occurring before the siege also helps to give a reason for the trust of the king in the LORD’s promise of deliverance.

2 Kings 20:12-21

12 At that time King Merodach-baladan son of Baladan of Babylon sent envoys with letters and a present to Hezekiah, for he had heard that Hezekiah had been sick. 13 Hezekiah welcomed them; he showed them all his treasure house, the silver, the gold, the spices, the precious oil, his armory, all that was found in his storehouses; there was nothing in his house or in all his realm that Hezekiah did not show them. 14 Then the prophet Isaiah came to King Hezekiah and said to him, “What did these men say? From where did they come to you?” Hezekiah answered, “They have come from a far country, from Babylon.” 15 He said, “What have they seen in your house?” Hezekiah answered, “They have seen all that is in my house; there is nothing in my storehouses that I did not show them.”

16 Then Isaiah said to Hezekiah, “Hear the word of the LORD: 17 Days are coming when all that is in your house and that which your ancestors have stored up until this day shall be carried to Babylon; nothing shall be left, says the LORD. 18 Some of your own sons who are born to you shall be taken away; they shall be eunuchs in the palace of the king of Babylon.” 19 Then Hezekiah said to Isaiah, “The word of the LORD that you have spoken is good.” For he thought, “Why not, if there will be peace and security in my days?”

20 The rest of the deeds of Hezekiah, all his power, how he made the pool and the conduit and brought water into the city, are they not written in the Book of the Annals of the Kings of Judah? 21 Hezekiah slept with his ancestors, and his son Manasseh succeeded him.

The envoys from Merodach-balaban based on the historical references we have also must have occurred before the siege of Jerusalem in the fourteenth year of King Hezekiah (around 701 BCE). We know the Merodach-balaban returned to power in Babylon in the aftermath of King Sargon of Assyria’s death in 705, and while Hezekiah was pulling away from Assyria’s control in Jerusalem, he asserted his independence from Assyria with Elamite support in the southeast. When King Sennacherib began to reestablish dominance, he turned initially against Babylon in 704-703 and ended Merodach-balaban’s brief resurgent reign. (Cogan, 1988, pp. 260-261)[2] If these two stories are linked in time it is likely occurring even earlier than the fourteenth year of Hezekiah, around 705-703 BCE. Chronicles indicates that the envoys are sent because of the manipulation of time as a sign to Hezekiah (2 Chronicles 32:31), but this is also probably more than mere curiosity about an astrological event. Merodach-balaban and Hezekiah have a common purpose in resisting Assyria and the visit of the envoys likely has political implications.

Hezekiah welcomes these gift-bearing emissaries as honored guests and shows off the wealth of his storehouses, the temple, and the king’s house.[3] Isaiah, who appears to have easy access to the monarch, asks about the visitors and what they have seen and then gives an oracle that in the future Babylon will be responsible for the removal of the wealth of Jerusalem as well as the descendants of Hezekiah.

Mordechai Cogan and Hayim Tadmor note that the language of the prophecy in verses seventeen to nineteen is closely related to the language of Jeremiah and not like the language of Isaiah, (Cogan, 1988, p. 259) but this would require the parallel language in Isaiah 39 to also be written by Jeremiah.[4] Ultimately, we know that the prophet Micah who was active during the time of King Hezekiah prophesies that Jerusalem will ultimately be destroyed, although Micah does not indicate Babylon as the vessel. (Micah 3:12) Micah’s prophecy reemerges in the story of Jeremiah (Jeremiah 26:18) to justify Jeremiah’s words against the city and king. It may seem strange for Babylon to enter the scene when it will shortly seem like a minor threat, but likely these words of Isaiah become central to the retelling of the final five chapters of the book which end with Isaiah’s words being fulfilled.

As a king, Hezekiah must navigate between the prophetic expectations of faithfulness exclusively to the LORD the God of Israel and the political and diplomatic requirements of running a kingdom. What may have been an act of alliance making and friendship to Hezekiah looks like an act of foolishness to Isaiah. Political matters can shift quickly, and today’s allies may be tomorrow’s adversaries, but the narrator of the book of Kings wants us to remember that God is where the kings of Judah derive their power, security, and peace.

King Hezekiah’s response and thoughts which the narrator convey have been read combining a pious response and an inner thought unconcerned about future generations. The response of Hezekiah echoes the words of his prayer earlier in the chapter as Alex Israel notes:

“The word of the Lord…is good (tov)…If there will be peace (shalom) and security (emet) in my days.” The terms tov, shalom, and emet, echo from his earlier prayer: “Remember…how I have walked before You in faithfulness (emet) and with a whole (shalem) heart, and have done what is good (tov) in your eyes” (II Kings 20:2) (Israel, 2019, p. 313)

Although it is easy to read his private thoughts as unconcerned about the future generations, there is a pious reading like the words of the priest Eli in 1 Samuel 3:18, “It is the LORD; let him do what seems good to him.” Ultimately the future rests in the LORD’s hands and the hands of future generations. Earlier in the chapter we have seen how a faithful king’s prayer can change the future with the LORD.

The reign of Hezekiah is closed with the customary relation of his entire reign which highlights his power and specifically the creation of a reliable water supply for the city. We noted the king’s works to fortify the city and to bring water into the city in our notes on chapter eighteen, and they have been historically documented with the discovery of the inscription on the Siloam pool. Hezekiah’s reign is consequential both for the development of a Zion theology where the city of Jerusalem, the temple, and the Davidic king are under God’s protection as demonstrated by the deliverance of Jerusalem from Assyria, but 2 Kings includes the prophetic critique of this belief. Hezekiah is a good king in the eyes of 2 Kings and Isaiah, although Micah indicates that the reforms of the king do not ultimately impact the nobility, priesthood, and the people, much as Jeremiah will indicate under Josiah. This also is emphasized with the rapid return under Manasseh to the ‘abominable practices of the nations’ and turn aside from Hezekiah’s faithfulness.

[1] This story is echoed in Isaiah 38, although the ordering of the story is slightly different and it includes a long song of thanksgiving in response to the healing.

[2] Merodach-balaban initially reigns in 710 BCE but is removed by Sargon and flees, he returns to power briefly five years later when Sargon dies in battle.

[3] Another indication that this is before the siege of Jerusalem when Hezekiah takes the wealth of the temple and the king’s house to attempt to pay tribute to King Sennacherib.

[4] Cogan and Tadmor’s commentary comes from a period that focused more on source criticism and looked for evidence of multiple sources behind a text. I find those arguments interesting but ultimately, I come from more of a canonical school where I look to comment on the text as we have received it. There is a tradition where Jeremiah is the one responsible for assembling the book of Kings and the Deuteronomic History in general.