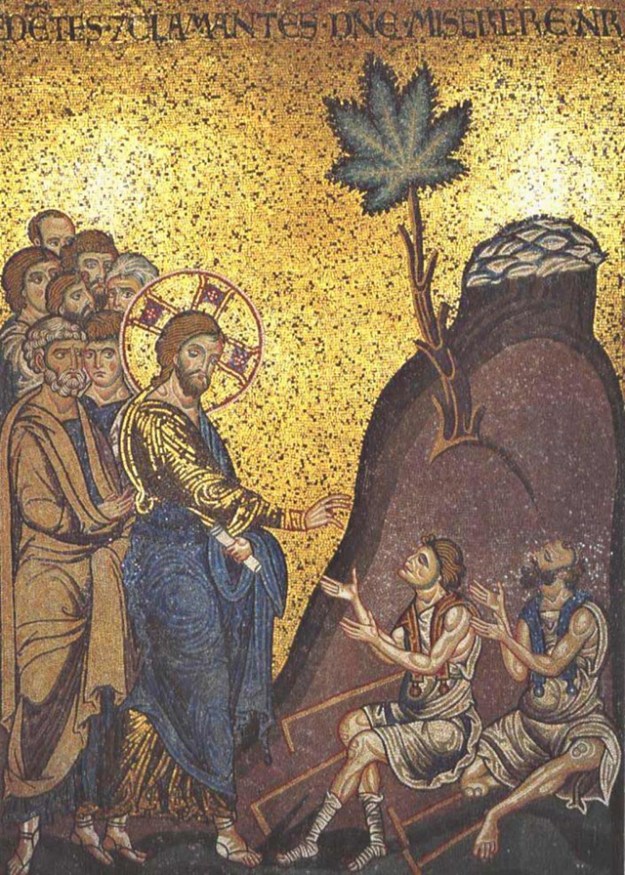

Saint John the Baptist in Prison Visited by Salome, Guercino (1591-1666)

Matthew 11: 1-15

Parallel Luke 7: 18-28

1 Now when Jesus had finished instructing his twelve disciples, he went on from there to teach and proclaim his message in their cities.

2 When John heard in prison what the Messiah was doing, he sent word by his disciples 3 and said to him, “Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?” 4 Jesus answered them, “Go and tell John what you hear and see: 5 the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news brought to them. 6 And blessed is anyone who takes no offense at me.”

7 As they went away, Jesus began to speak to the crowds about John: “What did you go out into the wilderness to look at? A reed shaken by the wind? 8 What then did you go out to see? Someone dressed in soft robes? Look, those who wear soft robes are in royal palaces. 9 What then did you go out to see? A prophet? Yes, I tell you, and more than a prophet. 10 This is the one about whom it is written,

‘See, I am sending my messenger ahead of you, who will prepare your way before you.’

11 Truly I tell you, among those born of women no one has arisen greater than John the Baptist; yet the least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he. 12 From the days of John the Baptist until now the kingdom of heaven has suffered violence, and the violent take it by force. 13 For all the prophets and the law prophesied until John came; 14 and if you are willing to accept it, he is Elijah who is to come. 15 Let anyone with ears listen!

Jesus concludes the instructions for his disciples, and we return to narrative where we are again confronted with the question of Jesus’ identity and authority. In chapters eight and nine we were drawn in a rhythm of stories of acts of power which disclosed Jesus’ identity and authority combined with stories interjected which point to the character of discipleship under Jesus. After Jesus completes his instructions for his disciples his encounter with a group of John’s disciples returns us to the reflections upon Jesus’ identity in chapter eleven which will use language strikingly similar to some other New Testament authors and link into themes in Paul (in this section), John (in the next section) and again Paul (in the final section). While Matthew may not develop these themes in the same what that Paul or John will it does at least allude to some common language and understandings about Jesus’ identity already being present in the time of the compilation of Matthew’s gospel and continues to point to Jesus’ identity being greater than even a title like Messiah (or Christ) can encompass.

The opening verse of chapter eleven transitions us from the instruction to narrative in a pattern commonly used in Matthew’s gospel (see also 7:27; 13:53; 19:1 and 26:1). The language of this transition is also similar to the language that Deuteronomy narrates Moses using at the end of each of his teaching of the twelve tribes of Israel (Deuteronomy 31:1, 31:24 and 32:45) and further heightens the connection between the twelve tribes of Israel and the twelve disciples. The translation of the Greek teleo here as ‘finished’ is appropriate and contrasts to the normal translation of the same term in Matthew 5:48 as ‘perfect’ which I address at length in that section. The word translated ‘instruction’ (Greek diatasso) has a firmer sense of commanding, ordering or directing and it reinforces the position of Jesus as one to give orders and to send out these followers into the prepared fields for harvest. Jesus may have completed giving instructions to his disciples, but he now moves towards the continued proclamation of the kingdom of heaven and teaching about how to live as a community under that kingdom to the cities on his journey.

Jesus has sent forth his disciples but in the presence of the crowds he receives the disciples of John who come to him and question his identity. John has heard in prison of what Jesus is doing, and the words behind the ‘what the Messiah is doing’ is literally the work of Christ (Greek erga tou Christou). Christ and Messiah are the same word (Messiah is the transliterated Hebrew and Christ is the transliterated Greek) and it refers to one who is anointed to rule. While Christ or Messiah or the Latin Rex all refer to kingship and John the Baptist’s reference to the work of the Christ probably indicates an understand Jesus in terms of the awaited king to reestablish the Davidic line and bring about the renewal of Israel. Yet, the works that Jesus is doing is not the work of a warrior king, like David, (at least not against the armies of Rome) but rather there is a different quality to the work of Jesus. John’s query through his disciples asking, “are you the one?” provides another query into the identity of Jesus and its meaning.

Jesus’ answer refers to the works narrated in chapters eight and nine, but their form also points back to language of Isaiah, particularly 35: 5-6:

Then the eyes of the blind shall be opened, and the ears of the deaf unstopped; then the lame shall leap like a deer, and the tongues of the speechless sing for joy. Isaiah 35: 5-6a

Being the Messiah or the Son of David is redefined in terms of healing rather than military conflict. In fact, the opposition to the kingdom of heaven’s approach will be by those who use violence to bring about peace. The kingdom of heaven is not the violently maintained Pax Romana which is enforced (often brutally) by the legions of the empire or the kings and rulers of the various provinces of the empire. The Christ as embodied by Jesus embodies both the characteristics of a prophet like Elijah or Elisha (who would heal and even raise the dead), a Moses who can give instructions to the nation of Israel but also a king with authority.

Jesus’ answer to John’s disciples ends in another beatitude, like the beginning of the Sermon on the Mount, where “blessed (happy) is anyone who takes no offense at me.” As I mentioned when discussing the beatitudes in Matthew 5, this takes us into the rhythm of wisdom literature where one is ‘blessed’ to be like the saying illustrates. Wisdom is going to be introduced in our next section, but here we are also by the Greek skandalizo which is the verbal form of skandalon used by Paul, for example in 1 Corinthians 1: 23:

but we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block (skandalon-scandal) to the Jews and foolishness to the Greeks.

Paul will in 1 Corinthians allude to the wisdom of God, which is Christ crucified, and as we will see as the conversation continues between Jesus and the crowd we will also be brought into an identification with Jesus and the character of wisdom. Here it is worth having one’s ear open to the identity being alluded to as Jesus redefines the expectations of Messiah initially in terms of healing and then highlighting the ‘offense’ that will cause many to choose the path of foolishness rather than wisdom.

As John’s disciples depart Jesus returns to the crowd to talk about the identity of John by extension his own identity. Jesus rhetorically negative responses about what the people went into the wilderness to encounter John the Baptist is a pretty direct jab at Herod Antipas. A reed shaken by the wind probably alludes to the coinage Herod Antipas issued which uses reeds on them. Reeds are common in Israel and while they are blown about by the wind because they are unreliable for strength. Jesus may be referring to the way Herod Antipas was ‘battered’ by John’s prophetic condemnation of his relationship with Herodias. This is sharpened by the ‘soft robes’ description. The word ‘soft’ can also be translated ‘effeminate’ which would be a strong criticism indeed in the ancient world. Herod is subtly accused of being weak, unreliable and non-masculine. John the Baptist is the contrast to Herod Antipas (even though he is imprisoned by him) and his role is that of a prophet and specifically the prophet sent to prepare the way.

Matthew uses scripture to point us to the identity of Jesus in surprising ways. Here he uses the same passage Mark quotes in relation to John the Baptist (see Mark 1:2 where Mark misquotes this as Isaiah). The reference is to Malachi 3: 1:

See I am sending my messenger to prepare the way before me, and the Lord whom you seek will suddenly come to his temple.

The use of Malachi is important because it is the end of Malachi where the hope for a return of Elijah comes:

Lo, I will send you the prophet Elijah before the great and terrible day of the LORD comes. He will turn the hearts of parents to their children and the hearts of children to their parents, so that I will not come and strike the land with a curse. Malachi 4: 5-6

John the Baptist’s identity is linked to Elijah who prepares the way for the coming of the LORD, the God of Israel, and by at least allusion Jesus is linked to the LORD. Messiah as a title is insufficient for who Jesus is in Matthew’s gospel. It, like the Son of David, Son of God, and Son of Man it points to a portion of Jesus’ identity but ultimately needs to be redefined in the terms of the ‘works of the Messiah.’ John the Baptist may be greater than any who came before him, but in the dawning kingdom of heaven even the least of its citizens are now greater than John for they are a part of a new thing. The crowd hearing the proclamation of Jesus stand at a critical time for they are seeing what the prophets and the law and John the Baptist all prepared the way for. What they are seeing and hearing is the fulfillment of the prophetic and covenantal hope of Israel.

Verse twelve and thirteen can be read multiple ways. The NRSV renders ‘the kingdom of heaven has suffered violence, and the violent take it by force. For all the prophets and the law prophesied until John came.’ In translating this there are two significant issues: first in the kingdom of heaven’s ‘suffering violence and being taken by force’ and secondly in the sense the prophets and the law ‘prophesied until John came.’ The first passage the Greek biazetai kai biastai arpazoousin auten is behind this phrase. Biazetai and biastai are a related verb and noun. While the NRSV’s translation of third person singular passive biazaetai as ‘has suffered violence’ is the traditional rendering of a verb that indicates entering by force it can also mean that the kingdom of heaven has entered forcefully or entered in power and in resistance to that power violent men have tried to force their way into the kingdom. The kingdom of heaven does come in power as illustrated by the healings and Jesus’ authority of sin, the demonic, creation and even death demonstrated in the previous chapters, but it will not be established by violence. There are conflicting visions between those who are looking to Jesus in terms of a traditional king or emperor whose peace is maintained by military force. Jesus himself will be seized by violent men and they will attempt to maintain their power through their violence. There is a conflict between the kingdom of heaven and those violent men who maintain the kingdoms of the earth, and the kingdom of heaven is not powerless, but it will not respond like a king or emperor. The second translational issue is whether the law and prophets have ceased their function after John came and that prophesy is at an end. I would keep the Greek word order and render the phrase ‘the law and the prophets up to John prophesied.’ There is a temporal aspect to this Greek phrase but the way the English rearranges the words in the NRSV can be read as John the Baptist bringing an end to prophecy where the Greek simply states that those who came before John and including John prophesied.

Moving back out of the translational reeds we do have in this exchange between the disciples of John, the crowds and Jesus a continued reflection on who John the Baptist is and by extension who Jesus is. John the Baptist, for those willing to hear is Elijah, and Jesus is the one for whom Elijah is preparing the way. Messiah or Christ as it is applied to Jesus needs to be understood in relations to the ‘works of the Messiah’ demonstrated by Jesus. The kingdom that Jesus proclaims and reigns over is not a kingdom created by violent men like the conquests by David or Caesar, but it is not without power. Its power may seem like foolishness to the Greeks and a stumbling block to the Jews in Paul’s language. Continuing in Paul’s language in 1 Corinthians and preparing us for the next section this ‘Christ Jesus, who became for us the wisdom of God’ is the Jesus who will be the one crucified by violent men is also the one in whom this paradoxical power of the kingdom of heaven resides. This power that allows, “the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news brought to them.”