1 Kings 12: 1-24 A Divided Kingdom

1 Rehoboam went to Shechem, for all Israel had come to Shechem to make him king. 2 When Jeroboam son of Nebat heard of it (for he was still in Egypt, where he had fled from King Solomon), then Jeroboam returned from Egypt. 3 And they sent and called him; and Jeroboam and all the assembly of Israel came and said to Rehoboam, 4 “Your father made our yoke heavy. Now therefore lighten the hard service of your father and his heavy yoke that he placed on us, and we will serve you.” 5 He said to them, “Go away for three days, then come again to me.” So the people went away.

6 Then King Rehoboam took counsel with the older men who had attended his father Solomon while he was still alive, saying, “How do you advise me to answer this people?” 7 They answered him, “If you will be a servant to this people today and serve them, and speak good words to them when you answer them, then they will be your servants forever.” 8 But he disregarded the advice that the older men gave him, and consulted with the young men who had grown up with him and now attended him. 9 He said to them, “What do you advise that we answer this people who have said to me, ‘Lighten the yoke that your father put on us’?” 10 The young men who had grown up with him said to him, “Thus you should say to this people who spoke to you, ‘Your father made our yoke heavy, but you must lighten it for us’; thus you should say to them, ‘My little finger is thicker than my father’s loins. 11 Now, whereas my father laid on you a heavy yoke, I will add to your yoke. My father disciplined you with whips, but I will discipline you with scorpions.'”

12 So Jeroboam and all the people came to Rehoboam the third day, as the king had said, “Come to me again the third day.” 13 The king answered the people harshly. He disregarded the advice that the older men had given him 14 and spoke to them according to the advice of the young men, “My father made your yoke heavy, but I will add to your yoke; my father disciplined you with whips, but I will discipline you with scorpions.” 15 So the king did not listen to the people, because it was a turn of affairs brought about by the LORD that he might fulfill his word, which the LORD had spoken by Ahijah the Shilonite to Jeroboam son of Nebat.

16 When all Israel saw that the king would not listen to them, the people answered the king,

“What share do we have in David? We have no inheritance in the son of Jesse. To your tents, O Israel! Look now to your own house, O David.”

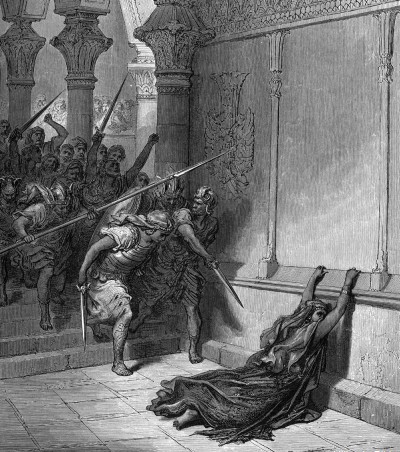

So Israel went away to their tents. 17 But Rehoboam reigned over the Israelites who were living in the towns of Judah. 18 When King Rehoboam sent Adoram, who was taskmaster over the forced labor, all Israel stoned him to death. King Rehoboam then hurriedly mounted his chariot to flee to Jerusalem. 19 So Israel has been in rebellion against the house of David to this day.

20 When all Israel heard that Jeroboam had returned, they sent and called him to the assembly and made him king over all Israel. There was no one who followed the house of David, except the tribe of Judah alone.

21 When Rehoboam came to Jerusalem, he assembled all the house of Judah and the tribe of Benjamin, one hundred eighty thousand chosen troops to fight against the house of Israel, to restore the kingdom to Rehoboam son of Solomon. 22 But the word of God came to Shemaiah the man of God: 23 Say to King Rehoboam of Judah, son of Solomon, and to all the house of Judah and Benjamin, and to the rest of the people, 24 “Thus says the LORD, You shall not go up or fight against your kindred the people of Israel. Let everyone go home, for this thing is from me.” So they heeded the word of the LORD and went home again, according to the word of the LORD.

At the end of Solomon’s reign, Israel is only three generations removed from a United Israelite kingdom being a collection of loosely affiliated tribal groups and territories. Solomon’s forty year reign put the kingdom on a fast track to becoming a powerful monarchy involved in global trade and with an aggressive set of building projects. Although Solomon attempted to replace the tribal power structures with a regional set of administrators to deliver the taxes and to conscript labor for the state projects there is a growing tension between Solomon’s Jerusalem based monarchy and the population which has borne the burden of these projects through both taxation of their (primarily) agricultural production and the physical labor of construction. The prosperity of Solomon’s reign may have given the illusion of Israel being a modern unified kingdom, but as Alex Israel states, “the seam between Judah and the other tribes is prone to unravelling.” (Israel, 2013, p. 154)

Rehoboam the son of Solomon comes to Shechem, one of the most important cities of the northern tribes of Israel, to be anointed as king. We do not know whether this is, at the behest of his advisors, a strategic political and symbolic move to honor the northern tribes and attempt to provide unity or a move to assert control over these tribes but it leads to the people giving voice to their dissatisfaction with the administration of Rehoboam’s father and their desire for change. There still seems to be a chance for the kingdom to remain united if Rehoboam will make some concessions to the people who have borne the taxation and labor of Solomon’s kingdom building. Additionally, the northern tribes may be concerned about the security situation on their borders with the rise of Rezon in Damascus and the selling off of Cabul to finance Solomon’s construction and acquisition of gold and other precious resources. It is likely that the northern tribes felt that they were being asked to carry a heavy yoke on behalf of the Solomon’s monarchy without sharing in the benefits of their burden. (Cogan, 2001, pp. 351-352) Jerusalem and Judah have grown wealthy and prosperous while northern Israel has lost territory, security, and the fruit of their labor. With their taxation they ask not for representation, but for their monarch to hear their plight and to be a king for all Israel, not merely the king of Judah and Jerusalem.

During the three days intermission in the story, Rehoboam consults two distinct groups of counselors for advice. One group of counselors are his father’s men who may remember a time before Solomon’s forty-year reign or who may have seen the cost the people of the land bore. Their advice of serving the people and giving kind words to them has the potential to ease the tensions which threaten to pull the seam between Judah and the other tribes apart. But the advice of the group derogatorily in Hebrew called ‘boys’ (hayla-dim) (NIB III: 102) only inflames the tensions. Rehoboam identifies with this group saying, “What do you advise that we answer this people.” It is likely that these comrades of Rehoboam have grown up knowing the affluence of Solomon’s court and have been insulated from the burden of the people. They probably have grown up in an environment where they never knew, in Brueggemann’s words,

anything but extravagant privilege and a heavy sense of their own entitlement. They likely take their affluence as normal and have never known anything other than a standard of living supported by heavy taxation. (Brueggemann, 2000, p. 156)

These ‘boys’ counsel their king and companion to display strength in defending their way of life. Solomon may have been a strong king who demanded much of the people, but Rehoboam will be build a stronger kingdom by being more demanding. The childish advice includes a graphic illustration of the potency of the new king by saying that his member[1] is larger than his father’s thigh. Rehoboam does not reiterate this part of the advice at the gathering of the people but he accepts the counsel of those who, like him, have benefited from the policies of his father and attempts to bluster the people into submission.

There is a common misperception among leaders, particularly leaders who are trying to portray themselves in a masculine manner, that misunderstands strength as toughness or cruelty. This occurs even in modern societies like the United States where a political leaders try to show how tough they are on crime or immigration by incredibly cruel policies or who try to assert dominance over their opponents. Often these leaders are not people of distinguished careers in the military or arenas of physical competition, but they create this persona of strength which may attempt to cover their own insecurities. This scene with the attempt by Rehoboam and his counterparts to bluster and dominate the nation with a heavier yoke and scorpions seems to be an attempt to show toughness through cruelty. The ‘scorpions’ mentioned may be a lash with metal edges, but whatever the meaning of this term it is designed to invoke pain greater than a whip.

The response of the people, “What share do we have in David? We have no inheritance in the son of Jesse. To your tents, O Israel! Look now to your own house, O David.” echoes an earlier incident in the reign of King David. In the aftermath of the rebellion of David’s son Absalom as weakened David is reconsolidating power in Israel when Sheba son of Bichri utters identical words (2 Samuel 19:1). David rallies his forces and his general Joab pursues Sheba and besieges the town of Abel of Beth-maacah until the residents throw the head of Sheba to the general.[2] David, through Joab, decisively deals with this fraying of the seams between the Judah and the other tribes. Yet, here the seam will not hold as the ten pieces of the new robe of the prophet Ahijah[3] separate from the two remaining pieces. We will see that Rehoboam is no David.

Rehoboam’s inability to accurately perceive the situation and his own weakness continues to make itself clear in response to the declaration of the people. Jeroboam may have been at work sowing dissent among the people, or the disillusionment of the people may be so great that it would lead to the rupture without any encouragement by Jeroboam. Rehoboam’s decision to send Adoram who was in charge of forced labor probably intended to continue to show this strength through toughness and cruelty, but it is an inflammatory and politically insensitive response to the people which result in the outbreak of violence and causes the king to flee in his chariot to Jerusalem. The strength and toughness he desired to demonstrate only highlighted his own impotence in the face of the rising rebellion.

In a final attempt to demonstrate strength Rehoboam rallies the forces of Judah and Benjamin. Apparently the Benjaminites remained while the other tribes departed, but the stated 180,000 men rallied to hold the kingdom together by force may be able to strike before the northern tribes and Jeroboam can organize. Yet, Shemaiah the man of God is able to communicate to the king where the other older voices have not been able. In contrast to King David his grandson Rehoboam will not reunite the nation through military action and he has no Joab to demonstrate his strength. But like his grandfather, Rehoboam will be sensitive to hearing the word of God and in this case acts accordingly.[4] The seam that brought the tribes of Israel together has unraveled and throughout the remaining history of the kings we will follow a progression of kings of Israel (the northern tribes) and the kings of Judah. There kingdom is rent asunder and there is no king or prophet who will be able to reunite the tribes.

1 Kings 12: 25-33 The Worship Places at Bethel and Dan

25 Then Jeroboam built Shechem in the hill country of Ephraim, and resided there; he went out from there and built Penuel. 26 Then Jeroboam said to himself, “Now the kingdom may well revert to the house of David. 27 If this people continues to go up to offer sacrifices in the house of the LORD at Jerusalem, the heart of this people will turn again to their master, King Rehoboam of Judah; they will kill me and return to King Rehoboam of Judah.” 28 So the king took counsel, and made two calves of gold. He said to the people, “You have gone up to Jerusalem long enough. Here are your gods, O Israel, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt.” 29 He set one in Bethel, and the other he put in Dan. 30 And this thing became a sin, for the people went to worship before the one at Bethel and before the other as far as Dan. 31 He also made houses on high places, and appointed priests from among all the people, who were not Levites. 32 Jeroboam appointed a festival on the fifteenth day of the eighth month like the festival that was in Judah, and he offered sacrifices on the altar; so he did in Bethel, sacrificing to the calves that he had made. And he placed in Bethel the priests of the high places that he had made. 33 He went up to the altar that he had made in Bethel on the fifteenth day in the eighth month, in the month that he alone had devised; he appointed a festival for the people of Israel, and he went up to the altar to offer incense.

Much of Solomon’s reign concentrated the worship of the LORD and the political power, military might, and the wealth of Israel in Jerusalem. Now as Jeroboam and the new kingdom of Israel finds itself adrift from this center of worship, power and wealth he begins to reestablish the nation around new centers and a new identity. Jeroboam’s position is tenuous as long as the central symbols of the people remain outside of the borders of this new territory. His reorganization of political life, religious life, and even the calendar will be judged harshly by the writer of 1 Kings who views these reforms through the perspective of Jerusalem and the temple. In the perspective of 1 Kings these are the ‘sins of Jeroboam’ that will become the reference for the negative evaluation of future kings of Israel.[5]

Jeroboam establishes two places of political and military power: Shechem and Peneul. Shechem is the site where the people rebelled against Rehoboam but it is also the site where Abimelech is the first in Israel to claim the title of king (Judges 9).[6] Yet, Shechem is probably chosen as a site due to its role in the stories of Abram and Jacob. Shechem is where God promises Abraham that his offspring will inherit the land (Genesis 12: 6-7), it is the unfortunate location of the rape of Dinah, the daughter of Jacob and her brothers’ revenge and where the family of Jacob leaves their foreign gods behind (Genesis 34) and where Joseph is sold into slavery by his brothers (Genesis 37: 12-36). Penuel also has a connection with the story of Abimelech’s father Gibeon (Judges 8)[7] but it is probably rebuilt for its connection to the story of Jacob. Penuel (or Peniel)[8] is the site where Jacob wrestles with the mysterious stranger and is renamed Israel (Genesis 32: 22-32). Establishing Israel’s new centers of political life around these two cities with associations with Abraham, Jacob, and Joseph gives a new geological and narrative root for this new nation of Israel to orient itself around.

Solomon’s centralization of the worship of the LORD around the temple in Jerusalem also presents a challenge for Jeroboam. He responds to this challenge by centering worship around two existing worship sites with new images. The narrator of 1 Kings wants us to hear in this story an echo of the story of the golden calf in Exodus 32 and places in Jeroboam’s mouth the same words that Aaron utters in that story, “These are your gods, O Israel, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt.” (Exodus 32:4) The two shrines at Bethel and in Dan become the locations of these new golden calves and for Israel replace the temple in Jerusalem. It is possible that the calves are not to be a replacement for the LORD, just a physical representation of the LORD (or like the bulls under the bronze sea in the temple designs ornamentation of the worship space). Yet, the author of 1 Kings views this innovation through the lens of the Exodus account of the golden calf and view Jeroboam’s reforms as evidence of his unfaithfulness to the LORD the God of Israel.

Additionally, the priests that Jeroboam appoints are not exclusively Levites. The text does not specifically state that no Levites were priests, but there were those from among the general public who became priests. In Exodus 32 the Levites were those who were most resistant to Aaron’s introduction of the golden calf and it is possible that there were Levites who resisted this, but there were Levites in the book of Judges who gladly used ephods and other icons as a part of the worship at shrines like the one in Dan.[9] Even the king functions as a priest, although Solomon also acted in this way in the dedication of the temple, but there is a complete reorganization of the religious life of the people around new shrines with new images and new priests. Finally there is a new calendar to orient the life of the people completely breaking with the ways of Judah.

In Canaan the bull is often associated with the deities of Baal and El[10] (Cogan, 2001, p. 358). 1 Kings tells us the narrative of Jeroboam from the perspective of Torah observance as shaped by the theology of Deuteronomy and Exodus. In light of that theological perspective the innovations of Jeroboam (like the innovations of Aaron) are judged negatively and harshly. The practices that Jeroboam adopts may have deeper roots in the worship history of the northern Israelite tribes that we will never know because their records have been lost to time. What we do have is the evaluation of those practices in the light of the perspective of 1 Kings which view this action as the ‘sin of Jeroboam’ that leads Israel astray.

[1] Can be translated finger but probably refers to his penis.

[2] This story in 2 Samuel 20 is a fascinating but twisted story of the power of David as exercised by Joab which is too complex to do more than point to as a parallel here.

[3] See previous chapter.

[4] In 2 Chronicles 12 Shemiah also confronts Rehoboam when King Shishak of Egypt attacks causing the king and his officers to humble themselves causing God to grant them deliverance. 1 Kings 14: 25-28 will mention the invasion of King Shishak but does not contain Shemiah’s role.

[5] Going forward I will follow 1 Kings’ practice of referring to the northern kingdom as Israel and the southern kingdom as Judah. The spilt is unfamiliar for many readers of scripture and the referral to the united monarchy as Israel along with the northern kingdom post Solomon can cause confusion, but no more than using other common references like Ephraim or even the northern kingdom.

[6] Abimelech never reigned over all Israel, he was a regional strongman whose short, violent domination of the area is the opposite of what judges were supposed to be.

[7] Gideon appeals to Penuel for food to support his pursuit of the kings of Midian but is rebuffed and later tears down their tower.

[8] Genesis uses both spellings in the story of Jacob.

[9] Judges 17-18

[10] El is a general term for god which is often a part of the names used to talk about the LORD the God of Israel, but may also refer to gods of other nations.