Matthew 24: 1-28

Parallel Mark 13:1-28; Luke 17:5-24,37b

As Jesus came out of the temple and was going away, his disciples came to point out to him the buildings of the temple. 2 Then he asked them, “You see all these, do you not? Truly I tell you, not one stone will be left here upon another; all will be thrown down.”

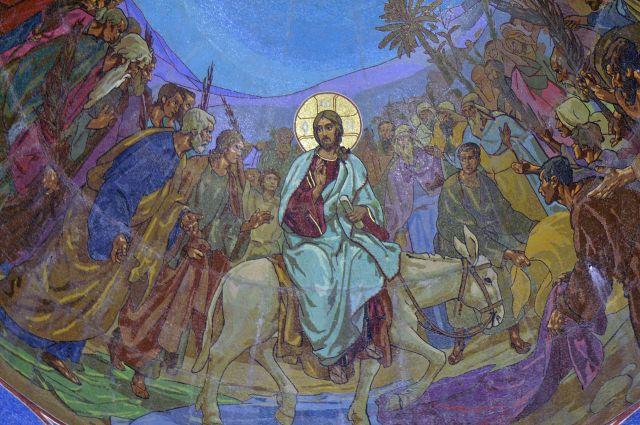

3 When he was sitting on the Mount of Olives, the disciples came to him privately, saying, “Tell us, when will this be, and what will be the sign of your coming and of the end of the age?” 4 Jesus answered them, “Beware that no one leads you astray. 5 For many will come in my name, saying, ‘I am the Messiah!and they will lead many astray. 6 And you will hear of wars and rumors of wars; see that you are not alarmed; for this must take place, but the end is not yet. 7 For nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom, and there will be faminesand earthquakes in various places: 8 all this is but the beginning of the birth pangs.

9 “Then they will hand you over to be tortured and will put you to death, and you will be hated by all nations because of my name. 10 Then many will fall away,and they will betray one another and hate one another. 11 And many false prophets will arise and lead many astray. 12 And because of the increase of lawlessness, the love of many will grow cold. 13 But the one who endures to the end will be saved. 14 And this good newsof the kingdom will be proclaimed throughout the world, as a testimony to all the nations; and then the end will come.

15 “So when you see the desolating sacrilege standing in the holy place, as was spoken of by the prophet Daniel (let the reader understand), 16 then those in Judea must flee to the mountains; 17 the one on the housetop must not go down to take what is in the house; 18 the one in the field must not turn back to get a coat. 19 Woe to those who are pregnant and to those who are nursing infants in those days! 20 Pray that your flight may not be in winter or on a sabbath. 21 For at that time there will be great suffering, such as has not been from the beginning of the world until now, no, and never will be. 22 And if those days had not been cut short, no one would be saved; but for the sake of the elect those days will be cut short. 23 Then if anyone says to you, ‘Look! Here is the Messiah!’or ‘There he is!’ — do not believe it. 24 For false messiahsand false prophets will appear and produce great signs and omens, to lead astray, if possible, even the elect. 25 Take note, I have told you beforehand. 26 So, if they say to you, ‘Look! He is in the wilderness,’ do not go out. If they say, ‘Look! He is in the inner rooms,’ do not believe it. 27 For as the lightning comes from the east and flashes as far as the west, so will be the coming of the Son of Man. 28 Wherever the corpse is, there the vultures will gather.

Among Christians in the United States, this chapter which is sometimes called the ‘little apocalypse’ has become difficult to hear for two opposing reasons. The first reason is the way this, and other texts in both the New Testament and Hebrew Scriptures often labeled apocalyptic have been used and obsessed over in various Christian theologies and groups which focus on the return or coming (Greek parousia) of Christ and the advent of God’s kingdom almost like a script out of a horror movie where a vengeful God inflicts God’s wrath on all who oppose God’s will. While there is a grain of truth in this perspective when it comes to God’s judgment, it is helpful to remember that the grain of truth has often been overwhelmed by a barn full of chaff laid upon it in many modern Christian theologies. The second struggle is that the enlightenment has regarded the apocalyptic as an embarrassment and has often attempted to distance itself from the concept of God’s intervention in the world. It is important to realize that what we often transform into fear was the hope of the early followers of Jesus, they longed for Christ’s return and expected it and were willing to endure the struggles of their time to proclaim what they felt was a gospel of hope. This message also helped the early church endure the loss of several key symbols to the Jewish worldview and to see the suffering of the present as the painful but ultimately life-giving birth pangs of God’s new kingdom emerging in the midst of the world.

The temple was a focal point of the Jewish people in Judea and beyond. The temple in Jerusalem takes up a large amount of the city’s overall footprint and as N.T. Wright can state helpfully,

Jerusalem was not, like Corinth for example, a large city with lots of little temples dotted here and there. It was not so much a city with a temple in it; more like a temple with a small city round it. (Wright 1992, 225)

Matthew is not explicit that with Jesus departing the temple that the presence of God has left the temple, but with Matthew’s Emmanuel theology which permeates the gospel it may be implied in this scene. The temple, for all the grandeur of its reconstruction, will soon for not only the Christians but also for the rest of the Jewish people, will be displaced as a central symbol of their faith with its destruction. The coming destruction of the temple and Jerusalem, which occurs in the Jewish War of 66-70 CE, will cause a crisis which forces both the Jewish people and the early followers of Jesus, both Jew and Gentile, to reexamine their faith in terms of a new central place where God will meet them. For the followers of Jesus, one greater than the temple is currently among them and for Matthew’s community they await his return.

One of the consistent struggles of the disciples throughout the gospel is attempting to understand Jesus’ message in light of the traditional symbols and paradigms the learned. They are still ‘little faith ones’ which see in part, trust in part but still are struggling to let go of the beliefs and practices they learned over a lifetime. They see the temple primarily as a structure dedicated to God’s service, and so the destruction of the temple and Jerusalem seem like the opposite of what to expect after the coming of the long-awaited Messiah. Just like Jeremiah’s message which often fell on deaf ears before the destruction of the temple and Jerusalem by Babylon, only to be remembered as the people reconstructed their identity in exile, these words of Jesus which at the time seemed strange, provided meaning, and hope in a future where the followers of Jesus are scattered among the nations. At a time when the Roman empire seems to be consumed by struggles for power, and when the early Christians themselves may be beginning to experience exclusion from their identity with the Jewish people and persecution among the nations these words encourage them to persevere.

Jesus’ proclamation of the kingdom of heaven has prepared his followers to expect God’s intervention in the world, and there are others in Judaism of the time who also expected God’s intervention in various ways. We know the Essenes and the Pharisees expected God to intervene in history to deliver Israel from its enslavement to foreign powers and (in the Essenes case) unfaithful shepherds leading in the temple. Jewish hope was not for an ending of the world, as is present in popular culture and several late Christian movements, but rather for a reordering of the world around God’s reign through Israel. When the disciples ask about Jesus’ coming (parousia) at the end of the eon (suntelias tou aionos)[1] they are not asking about the end of the world but the advent of God’s kingdom which will replace the kingdoms of Herod or the empire of Caesar. The idea of Christ’s return is probably imagined in imagery similar to a celebration after one of King David’s victories. The other source of imagery would be the celebrations of imperial might by Caesar, but these would be considered only a parody of the expected victorious celebration of the advent of the kingdom of heaven on earth. Yet, Jesus does not answer the disciples with signs of his coming to inaugurate the kingdom of heaven but instead gives warnings about events, false prophets and false messiahs/Christs which will lead people to trust in the wrong things.

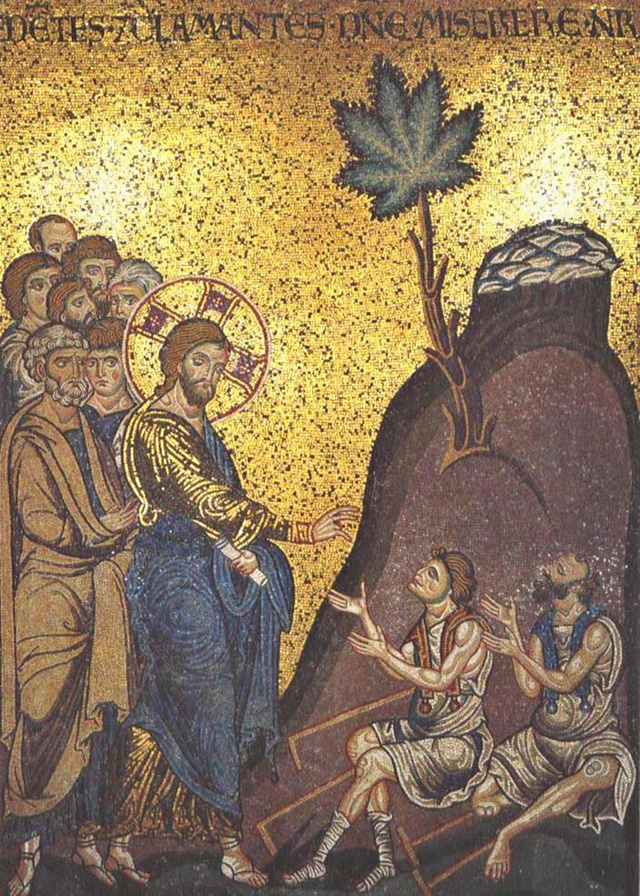

Jesus warns his disciples “See (blepete) that no one leads you astray.” While the NRSV’s use of beware does capture the sense of warning, the disciples are to take an active role in ensuring that they do not follow false prophets and false Christs. It is helpful to remember that Christ and Messiah are the same term, ultimately meaning anointed king, in Greek and Hebrew respectively rather than a part of Jesus’ name. Others will come claiming the same title that Peter has previously applied to Jesus, and they will gather followers. It is helpful to know that in the decades after Jesus’ death there would be those making the claim to be the ‘king of the Jews’ who would lead the people of Judea in multiple uprisings against Rome (not only the Jewish War of 66-70 which resulted in the destruction of Jerusalem, but also the 115-117 Jewish revolts in Egypt, Cyrene and Cyprus and the 133-135 rebellion of Bar-Kochba). This was a violent time for the Jewish people, and these followers of Jesus were not to follow these claimants who are attempting to establish God’s kingdom by force. Jesus’ followers are not to look for certain events which herald the advent of God’s kingdom on earth but to continue in their mission of teaching and proclamation to all nations. As Richard B. Hays can state, “The reality of the final judgment is crucial for Matthew, but not its timing.” (Hays 1996, 104) If these followers of Christ seek meaning in the midst of the struggle that is coming it can be read in the feminine imagery of ‘birth pangs’ that must occur before the advent of the new kingdom, or new creation in Paul’s language[2].

The suffering of these followers of Jesus in the midst of wars and rumors of wars, famines, and earthquakes in to be expected. As Jesus could tell them in the Sermon on the Mount, “Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” (5:10) now they are told they will face ‘oppression’[3] and some will be killed. Matthew, unlike Mark and Luke, indicates that this oppression will come from the nations[4] instead of perhaps their own people which may be assumed in Mark and Luke and this may reflect the situation of Matthew’s community being away from Judea and experiencing persecution primarily from sources outside the Jewish people. Even among the community of Jesus followers some may be ‘caused to stumble,’[5] and others will ‘hand over,’[6] and hate will enter into these communities formed around loving God and one’s neighbor. In addition to false Christs there will be false prophets who tell people a message that did not come from God. The identity of the community is at stake here. Anna Case-Winters helpfully illustrates:

Lawlessness will afflict them and “the love of many will grow cold (v.12). This latter is perhaps the most serious threat for Matthew. Lawlessness (Greek anomia) is the ultimate crisis for a community centered around Torah. For love to “grow cold” signifies the loss of the very heart of Torah, which is love of God and neighbor. (Case-Winters 2015, 271)

The crisis of oppression, death, stumbling, betrayal, and hate threaten to extinguish[7] the love that the community is grounded in. But those who endure to the completion[8] will not be left on their own. This scene anticipates the great commission with its promise of both the authority and presence of Christ as well as the commission to take this gospel to all nations. As David Garland can helpfully state,

the church is not to circle the wagons until the danger passes but is to engage in active mission. In spite of the trauma, the community’s responsibility to love and proclaim the gospel of the kingdom remains in force. (Garland 2001, 242)

Matthew, who has been intent throughout the gospel in helping the reader understand scripture, adds the citation of Daniel to the comment about the ‘blasphemy’[9] standing in the holy place so the reader might find:

Forces sent by him shall occupy and profane the temple and fortress. They shall abolish the regular burnt offering and set up the abomination that makes desolate. Daniel 11:31

Daniel, which most scholars would say is pointing to Antiochus IV Epiphanes a Seleucid king who persecuted the Jewish people leading to the Maccabean revolt, is now read in light of the actions of the Romans conquering the temple and removing the holy items for their victory parade in Rome. Instead of being drawn into this conflict with the empire of Rome, those followers of Christ in Judea are to flee. The war, which will continue beyond 70 as the imperial forces continue to quell their rebellious Jewish province, will indeed bring great suffering for the people of Judea. Ironically, these warnings to flee throughout this chapter are misread drastically by some later Christians into talking about a ‘rapture’ where the hope is to be the one taken but to the original hearers they would understand this as a warning to prepare to flee on short notice. They may need to flee without packing, without re-entering the house or taking additional garments.[10] Into this time of great affliction (thlipsis) those claiming authority as leaders, or those who claim the authority to interpret God’s will as prophets will come claiming to create meaning out of the suffering, but they are telling a false story. These false prophets and false Christs, who most likely portrayed themselves as being the saviors of Israel from her oppressors, were probably an attractive alternative to the message of Matthew’s community and the gospel they proclaimed. Yet, they are warned not to go out seeking these leaders and prophets.

To the early community of Jesus followers these warnings probably were intended to keep them away from the revolutionary movements gaining strength in Judea, Galilee and beyond. Matthew’s closing line that Wherever the corpse is, there the eagles[11]will gather may refer to the massing of Roman standards (eagles) gathered around Jerusalem. Although I believe Warren Carter rightly discerns the echo of Rome in this verse, I believe he misinterprets the direction of the verse. Carter indicates that the verse indicates a judgment on Rome and the corpse is the Roman army, (Carter 2001, 87-88) but I believe the plainer reading in the context is to avoid Judea and Jerusalem in revolt where the legions assemble to wage war against the revolt. The corpse may refer to the crucifixion, to the temple (especially in the context of this chapter) or to Jerusalem, but the geographical location would be understood.

In a passage like this one, especially where I have covered a lot of historical ground, it is perhaps more difficult to allow it to speak to the church today, yet I believe there is no way to separate Christianity from the apocalyptic portions of its scriptures. Every time one prays the Lord’s Prayer asking for God’s kingdom to come and God’s will to be done on earth as it is in heaven, one is praying for God’s intervention to bring about God’s promised new eon. Yet, throughout the gospel and throughout history there have been forces which are opposed to God’s reign and the changes that will bring. What may be perceived as a blessing to the poor in spirit, the meek, those hungering and thirsting for righteousness and the others mentioned in the beatitudes may be experienced as a woe to those who have become invested in the maintaining of the current order or who may want to bring about God’s order in their own terms. This chapter, even as it has been frequently misused in modern times, holds a key insight for the way of Christ: it is a way of hope even as one endures suffering. The Christians were not zealots who attempted to bring about God’s order by driving out the Gentiles from the promised land, rather they were those sent into the nations bearing witness to the gospel of peace. They meet violence by turning the other cheek, the learn to find blessing even when they are oppressed, and they find meaning amidst the times of affliction and tribulation by trusting in God’s hearing of their prayers and acting on them. This is a hope that would be at home in the psalms and the prophets and has sustained Christians for millennia. It is a hope that has sustained non-violent groups through the years and as I write this the lyrics of “We Shall Overcome,” used in the civil rights movement but has its origins in Charles Tindley’s adaptation of the 19th Century Spiritual “No More Auction Block for Me.” Oh deep in my heart, I do believe, that we shall overcome one day, and that overcoming comes when God changes the world bringing down the mighty and lifting up the lowly. Until that day we work, and we wait, and we suffer, and we hope. We hold fast to what we have received and are alert for false prophets and false messiahs which proclaim cheap and easy paths to claiming God’s kingdom

[1] We again encounter the common Matthew word telos, here with the prefix sun attached to it, meaning completion, consummation, end. I think the older word eon is helpful, since it is both a direct transliteration of the Greek aion but also does not have some of the baggage of ‘the end of the age’ in Christian parlance.

[2] Paul can also use the imagery of labor pains of the creation giving birth to something new in Romans 8:18-25

[3] This is the Greek word thlipsis which occurs twice in this passage meaning ‘oppression, affliction, or tribulation’

[4] Ethnos can also be translated Gentiles.

[5] This is a passive form Scandalizo, where we get the English scandalize from, which has the connotation of stumbling. Has been used frequently in Matthew.

[6] Paradidomi is an important word in all the gospels which means both betray, but more literally to hand over (presumably into another’s custody)

[7] The Greek Psucho can mean grow cold or extinguish. I think the future indicative tense leads to the more absolute reading, especially when paired with lawlessness.

[8] Telos again used as a term of completion in verses 13 and 14.

[9] Bdelugma-blasphemy, abomination, detestable thing. NRSV ‘desolating sacrilege’

[10] Imation, which is translated a coat by the NRSV, means garments or clothing in general.

[11] Aetoi can be translated vultures, as the NRSV does, but it often refers to eagles