Lamentations 3

1 I am one who has seen affliction under the rod of God’s wrath;

2 he has driven and brought me into darkness without any light;

3 against me alone he turns his hand, again and again, all day long.

4 He has made my flesh and my skin waste away, and broken my bones;

5 he has besieged and enveloped me with bitterness and tribulation;

6 he has made me sit in darkness like the dead of long ago.

7 He has walled me about so that I cannot escape; he has put heavy chains on me;

8 though I call and cry for help, he shuts out my prayer;

9 he has blocked my ways with hewn stones, he has made my paths crooked.

10 He is a bear lying in wait for me, a lion in hiding;

11 he led me off my way and tore me to pieces; he has made me desolate;

12 he bent his bow and set me as a mark for his arrow.

13 He shot into my vitals the arrows of his quiver;

14 I have become the laughingstock of all my people, the object of their taunt-songs all day long.

15 He has filled me with bitterness, he has sated me with wormwood.

16 He has made my teeth grind on gravel, and made me cower in ashes;

17 my soul is bereft of peace; I have forgotten what happiness is;

18 so I say, “Gone is my glory, and all that I had hoped for from the LORD.”

19 The thought of my affliction and my homelessness is wormwood and gall!

20 My soul continually thinks of it and is bowed down within me.

21 But this I call to mind, and therefore I have hope:

22 The steadfast love of the LORD never ceases, his mercies never come to an end;

23 they are new every morning; great is your faithfulness.

24 “The LORD is my portion,” says my soul, “therefore I will hope in him.”

25 The LORD is good to those who wait for him, to the soul that seeks him.

26 It is good that one should wait quietly for the salvation of the LORD.

27 It is good for one to bear the yoke in youth,

28 to sit alone in silence when the LORD has imposed it,

29 to put one’s mouth to the dust (there may yet be hope),

30 to give one’s cheek to the smiter, and be filled with insults.

31 For the LORD will not reject forever.

32 Although he causes grief, he will have compassion according to the abundance of his steadfast love;

33 for he does not willingly afflict or grieve anyone.

34 When all the prisoners of the land are crushed under foot,

35 when human rights are perverted in the presence of the Most High,

36 when one’s case is subverted — does the LORD not see it?

37 Who can command and have it done, if the LORD has not ordained it?

38 Is it not from the mouth of the Most High that good and bad come?

39 Why should any who draw breath complain about the punishment of their sins?

40 Let us test and examine our ways, and return to the LORD.

41 Let us lift up our hearts as well as our hands to God in heaven.

42 We have transgressed and rebelled, and you have not forgiven.

43 You have wrapped yourself with anger and pursued us, killing without pity;

44 you have wrapped yourself with a cloud so that no prayer can pass through.

45 You have made us filth and rubbish among the peoples.

46 All our enemies have opened their mouths against us;

47 panic and pitfall have come upon us, devastation and destruction.

48 My eyes flow with rivers of tears because of the destruction of my people.

49 My eyes will flow without ceasing, without respite,

50 until the LORD from heaven looks down and sees.

51 My eyes cause me grief at the fate of all the young women in my city.

52 Those who were my enemies without cause have hunted me like a bird;

53 they flung me alive into a pit and hurled stones on me;

54 water closed over my head; I said, “I am lost.”

55 I called on your name, O LORD, from the depths of the pit;

56 you heard my plea, “Do not close your ear to my cry for help, but give me relief!”

57 You came near when I called on you; you said, “Do not fear!”

58 You have taken up my cause, O LORD, you have redeemed my life.

59 You have seen the wrong done to me, O LORD; judge my cause.

60 You have seen all their malice, all their plots against me.

61 You have heard their taunts, O LORD, all their plots against me.

62 The whispers and murmurs of my assailants are against me all day long.

63 Whether they sit or rise — see, I am the object of their taunt-songs.

64 Pay them back for their deeds, O LORD, according to the work of their hands!

65 Give them anguish of heart; your curse be on them!

66 Pursue them in anger and destroy them from under the LORD’s heavens.

This third poem in Lamentations intensifies the acrostic pattern exhibited in the first two poems. In Lamentations one and two each stanza, as noted by the verse numbers in those poems, begins with a successive letter of the Hebrew alphabet. In Lamentations three we jump from twenty-two to sixty-six verses because every line of the three-line stanzas begins with the appropriate letter. Three verses for aleph, three for bet, and through the Hebrew alphabet to tav. Although the poem is approximately the same length as the previous two poems the poet increases their reliance on form in a way only exceeded by Psalm 119 which has eight verses utilizing each starting letter as it moves through the acrostic pattern.

In poetry form matters. Acrostic is a form used to denote completion, and it brings an external order to a disordered world. Like the acrostic poem of Psalm 25, the poet attempts to reconcile the promises of the steadfast love (hesed) of God in a world where that love is challenged by the absence of God’s protection or the presence of God’s wrath. It is an act of faith that holds onto the language the poet learned throughout their life in a time where their life is turned upside down. Yet, here in this central poem of the book of Lamentations we do get a small glimmer of hope and as Kathleen O’Connor suggests, like Jeremiah 30–33, the placement of hope at the center may be intentional, yet that hope “remains muted at best.” (NIB VI: 1057)

In the first two poems there were two primary voices: the feminine voice of daughter Zion and the masculine voice of the witness reporting on daughter Zion’s experience of trauma, destruction, grief, and rage. In the second chapter of Lamentations this witness transforms into an advocate for daughter Zion unable to remain a passive observer. Yet, in this third chapter or third poem the voice throughout is that of a man. The first two poems have examined the impact of war and defeat on a feminine voice, but now the impact is viewed through a male lens. The NRSV overcorrects in its agenda for inclusive language when in the initial verse it translates “I am one.” The Hebrew geber may not mean warrior but it does have a definitively macho sense of standing up for oneself and others who are defenseless. The geber is a defender of women, children, and other non-combatants. In Job 38:3 and 40:7 this is the term utilized when Job is commanded by God to “Gird up your loins like a man (geber), I will question you and you shall declare to me.” The experiences of men and women are different and what they experience in this moment of defeat are different. Now this man, in the poem, who was supposed to provide security for the women and children of Judah stands, “injured, struck down, shot, pursued, captured, chained up, terrified, defeated, and taunted.” (Goldingay, 2022, p. 125) This man has lost two of the primary components of masculine identity traditionally understood. They have lost their ability to protect those under their protection and to provide for themselves and others.

Also in the first verse, the NRSV introduces that the man has suffered under the rod of God’s wrath, although God is not mentioned in the Hebrew at this point. Although from the first two poems as well as the later imagery of this poem we know that ultimately God is the one responsible for the suffering of the man and those around him, the one who causes the suffering is not explicitly named until verse eighteen when the LORD is finally named. Although it is the speaker’s God, the LORD of Israel, who is responsible for all the violent actions upon this man it may be that in the initial declaration of suffering it is difficult to voice that the LORD of steadfast love became the bringer of affliction and wrath in this moment.

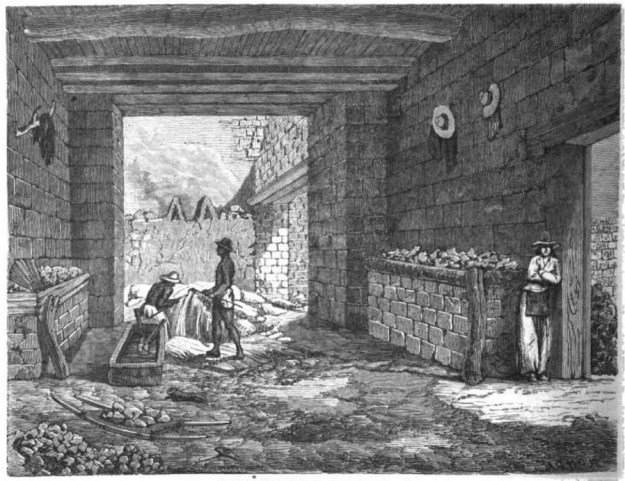

Violent verbs drive the action that has broken this man into a world of darkness. This was not a single wound that the man can recover from, but his assailant has turned his hand against this once strong man again and again. Flesh, bone, and skin: the whole of his person is devastated and although he still lives and speaks in pain he is on the path to becoming a resident of the broken boneyard of Ezekiel 37. The language then moves to the language of siege and imprisonment. The people of Judah would have recently experienced the siege, and imprisonment was typically a political punishment in the Middle East rather than the default punishment for wrongdoings in became in Western societies.[1] Poetry does not need to be consistent to be powerful. On the one hand the man is surrounded and besieged, on the other he is isolated and alone. Ultimately the besieging and imprisoning presence has cut him off from world and most critically for the poet, from God’s steadfast love.

Martin Luther once spoke of the wrath of God as God’s alien work, while the grace of God was God’s proper work. Although still unnamed, it has become clear that the LORD has become like a dangerous animal[2] waiting to attack or an archer with this strong man in his sights. He has fallen from being a person worthy of respect to the laughingstock of the people. The good things have turned to bitterness, and wormwood a plant with a strong smell, bitter taste and reputation for toxicity (Goldingay, 2022, p. 134) utilized in the prophet Jeremiah’s writings,[3] becomes the unappealing drink provided. This once strong man now lies with his face and teeth on the ground among the gravel and cowering in ashes either in mourning or more likely in the aftermath of the destruction of Jerusalem. This man’s life (nephesh)[4] has been deprived of peace (shalom) and happiness (tob). Finally in verse eighteen we have the LORD named when all that the man had hoped from the LORD is gone. Reflection on his desperate and homeless situation only brings more bitterness.

Faith is not a straight path. Grief also is not a linear journey. This man has moved from bitterness to a remembrance of the faith he learned and the God he still trusts. The steadfast love of the LORD never ceases, his mercies never come to an end becomes a pivot point in this poetic reflection as the faith this man has learned is confronted by the reality of a life made bitter. The LORD is his inheritance and the one he can hope in. The good (happiness NRSV) that the man has forgotten is now emphasized as the starting word of the three ‘tet’ verses[5] which each begin with tob (good). Good is the LORD, good that one should wait, good that one should bear. The path of faithfulness that the man discerns is one of seeking God, staying silent and submissive, and bearing the suffering that is imposed, of bowing down and turning the other cheek. God will turn from wrath to grace because that is the character of the LORD of the man’s faith.

Verses thirty-four to thirty-six are translated as a question in most English translations, but the question form is not required in Hebrew. Another possible reading of these verses is that God does not see the way prisoners are crushed, and human rights are being violated, and justice is subverted. Yet, this also conflicts with the faith the man has learned where the LORD is responsible for everything both good and bad.[6] So the man turns inward to examine whether he individually and his people collectively have sinned testing and examining their ways. Ultimately the man’s verdict is that we have transgressed but also you have not forgiven. This final realization for the man forms a final pivot where the path of silence and submission is left aside for a final protest even more heated than the first. For this man the difference between the character of God represented by steadfast love and the experience of God as unforgiving requires him to raise his voice to attempt to pierce God’s obscuring anger.

The problem is that the God who sees and hears is shielding Godself from seeing and hearing. Wrapped in anger and a cloud no prayer can pass through God has abandoned the people. The poet digs into their humiliation and declares that God has made them filth and rubbish among the people. We open our mouths and God does not hear, but our enemies open their mouths, and we cannot help but hear them. Panic and pitfall, devastation and destruction[7] have come upon the man and his people and like both daughter Zion and the witness in the previous two psalms[8] his eyes flow an unceasing river of tears. Yet, these tears are now a part of this man’s protest to God. He can be broken in body and spirit, eating the dirt and covered in ashes, isolated and imprisoned, and caught up in a seemingly unending flood of tears if God will see. This man is able to remember God’s words from the past, “Do not fear!” the only words attributed to God in the book of Lamentations, but even these words come from the past. In repetitive fashion this poet calls on God as the ‘you’ who can act. Ultimately ‘You’ the LORD have heard their taunts and in the final verses this man asks for what daughter Zion cried for. Treat my enemies the way you have treated me. You have punished me for my transgressions, now punish them. I have known the anguish of the heart as I sit here in dust and ashes, the object of their taunt songs, let them know the impact of your curse on their lives. I have seen affliction under your wrath, turn your anger to them and destroy them. The poems of Lamentations attempt to make sense of a world that makes no sense. It is highly ordered by the poetic structure as it encounters a disordered world. It attempts to reconcile the faith in a God of steadfast love with the experience of God’s wrath. Their world, their home, their lives, and their relationship with their God is broken. They speak these words into the silence of the void waiting for an answer from their LORD which they have not received. This man, geber, is attempting to gird his loins like Job and stand before God and pierce the cloud of God’s wrath which seems to have silenced prayers. It is an act of audacity, but we inherited an audacious set of scriptures.

[1] There is no provision in the Torah for imprisonment. Jeremiah in Jeremiah 38 was imprisoned not because he broke no laws but because he was an annoyance to the leaders in Jerusalem.

[2] Bear and lion are paired as dangerous animals (Hosea 13;8; Amos 5:19) (Goldingay, 2022, p. 132)

[4] The Hebrew nephesh often translated soul in English is a very different concept than most modern conceptions of ‘soul.’ For Hebrew the nephesh is about life and not about something that is freed after death.

[5] Verses 25-27 which begin with the Hebrew letter ‘tet.’

[6] See my Reflection: A Split In The Identity of God.

[7] The NRSV does a good job of capturing the alliteration of this phrase in Hebrew.

[8] 1:16; 2:18.