Exodus 10: 1-2- The Hardening of the Heart

Then the LORD said to Moses, “Go to Pharaoh; for I have hardened his heart and the heart of his officials, in order that I may show these signs of mine among them, 2 and that you may tell your children and grandchildren how I have made fools of the Egyptians and what signs I have done among them — so that you may know that I am the LORD.”

The hardening of Pharaoh’s heart and the heart of the officials of Pharaoh within this story is a place where the hearer has to make a choice based upon their own theological leanings how to take the story. I discuss this initially back in chapter seven, but since we now hear for the first time, “for I have hardened the heart of Pharaoh and his officials” it is worth revisiting this discussion. As Walter Brueggemann can say when we search for an Old Testament theology and way of discussing the LORD, the God of Israel:

Old Testament theology, when it pays attention to Israel’s venturesome rhetoric, refuses any reductionism to a single or simple articulation; it offers a witness that is enormously open, inviting, and suggestive, rather than one that yields settlement, closure, or precision. (Brueggemann, 1997, p. 149)

The people of Israel, and the book of Exodus in particular, do their theology in narrative, prose, proclamation and song. They never construct a systematic way of talking about God nor do they have any struggle with paradox. Modern questions of ‘divine determinism’ verses ‘free will’ do not find a single answer even within the same book and often within the same story seeming contradictory views inhabit the same space. With this suggestive language of Pharaoh’s heart being hardened by the LORD here there are a number of ways to use this narrative. One reading of Pharaoh’s heart being hardened would be centered around the power of the LORD being uncontested. This conflict between the gods of Egypt and the LORD the God of Israel, which occurs around the meetings of Moses and Pharaoh, the LORD’s dominance is demonstrated by the leader of the empire of the day not even being in control of his own will power. In this case Pharaoh becomes a tragic and sympathetic figure who is merely a pawn in a much larger game. It also suggests a side of the LORD that demands to be taken seriously and who will have his actions told for generations to come. The signs may serve a teaching function for both the people of Israel and for Egypt. In the increasing pressure put upon the Egyptians there has always been a restraint where the damage to the Egyptian people was recoverable. Yet, here at the point where the consequences are becoming lethal the LORD seems determined, in the narrative at least, to see these signs go to their end.

Others will resist this type of reading preferring to have Pharaoh retain his free will and thus his culpability in resisting the LORD and the freedom of the people of Israel. We may want to have Pharaoh be the scapegoat, and there will be plenty in what follows where I call attention to an abusive dynamic in Pharaoh’s words, and yet the Hebrew scriptures always seem to resist easy answers to a complex world. Coming from a Christian perspective we often want to blame evil of sin and yet even within the New Testament there is always a place reserved for some external force of evil, whether in the form of Satan, demons or principalities and powers, that resists God. Here again, Brueggemann’s words are illuminating:

We may say that all such evil is the result of sin, but Israel resists such a conclusion, if by sin is meant human failure. Evil is simply there, sometimes as a result of human sin, sometimes as a given, and occasionally blamed on God. (Brueggemann, 1997, p. 159)

At least in chapter ten of Exodus the narrative resists an easy tying of Pharaoh’s actions to the consequences for his will has been hardened. The empire of the Egyptians has been made foolish, it has not acted foolish on its own. It is perhaps an uncomfortable ambiguity that the text invites us into. Yet, perhaps in its suggestive nature it may also enable us to see ourselves in the picture of the oppressor. Whether the power over the people of Israel and the economic benefit at their expense is an addiction for Pharaoh or whether he is unable to see another way or whether he is simply one more example of a leader made foolish we will never know. Yet, as we continue with this narrative I think it is important to not try to force the text to fit a theology we would impose upon it. I believe there is wisdom in its uncomfortable but suggestive way that evades simple answers.

Exodus 10: 3-11- Abusive Dynamics

3 So Moses and Aaron went to Pharaoh, and said to him, “Thus says the LORD, the God of the Hebrews, ‘How long will you refuse to humble yourself before me? Let my people go, so that they may worship me. 4 For if you refuse to let my people go, tomorrow I will bring locusts into your country. 5 They shall cover the surface of the land, so that no one will be able to see the land. They shall devour the last remnant left you after the hail, and they shall devour every tree of yours that grows in the field. 6 They shall fill your houses, and the houses of all your officials and of all the Egyptians — something that neither your parents nor your grandparents have seen, from the day they came on earth to this day.'” Then he turned and went out from Pharaoh.

7 Pharaoh’s officials said to him, “How long shall this fellow be a snare to us? Let the people go, so that they may worship the LORD their God; do you not yet understand that Egypt is ruined?” 8 So Moses and Aaron were brought back to Pharaoh, and he said to them, “Go, worship the LORD your God! But which ones are to go?” 9 Moses said, “We will go with our young and our old; we will go with our sons and daughters and with our flocks and herds, because we have the LORD’s festival to celebrate.” 10 He said to them, “The LORD indeed will be with you, if ever I let your little ones go with you! Plainly, you have some evil purpose in mind. 11 No, never! Your men may go and worship the LORD, for that is what you are asking.” And they were driven out from Pharaoh’s presence.

One of the insights I had in looking at this passage this time was the way in which Pharaoh attempts to maintain control of Israel in a dynamic that is similar to what may happen with an abuser. Previously, at the end of chapter nine, Pharaoh has acknowledged that he has sinned, that he has done wrong but refused to let the people go. Here the officials of Pharaoh, who previously the chapter mentioned had their hearts hardened, appeal to Pharaoh and implore him to let the people go. Pharaoh reluctantly is willing to make provision for the men only to go but wants to maintain control of the women, children and flocks of the Hebrews. He attempts to maintain control of the people and property that will force the men (and people as a whole) to return and submit to slavery and servitude.

As Pharaoh’s power becomes less his desperation is becoming greater in dealing with Moses and Aaron. Previously Moses and Aaron have left on their own terms but here they are driven from Pharaoh’s presence. Yet Pharaoh’s words here speak an unintended truth: “The LORD indeed will be with you, if I ever let your little ones go with you!” The presence of the LORD and the action of the LORD on the behalf of the people of Israel will be a major theme of Exodus. The LORD is with Moses and is active in a way that the forces of Pharaoh, the secret acts of the magicians and wise men, and ultimately the gods of Egypt cannot match.

The coming eighth sign once again will use the insignificant to humble a Pharaoh who refuses to be humbled. Previously frogs, gnats (or lice), and flies showed how the smallest of things could bring an empire to its knees. Pharaoh’s officials have seen before that these things are ‘the finger of the LORD’ and that at this point Egypt is ruined. Yet, Moses and Aaron and the people of Israel continue to be a snare that the king of Egypt is trapped within. Whether through his own stubbornness or divine hardening he is trapped within his role as the oppressor and refuses (or is unable) to imagine a world where his empire is not built upon the servitude of an enslaved people.

Exodus 10: 12-20- Locusts and the Loss of Agriculture

12 Then the LORD said to Moses, “Stretch out your hand over the land of Egypt, so that the locusts may come upon it and eat every plant in the land, all that the hail has left.” 13 So Moses stretched out his staff over the land of Egypt, and the LORD brought an east wind upon the land all that day and all that night; when morning came, the east wind had brought the locusts. 14 The locusts came upon all the land of Egypt and settled on the whole country of Egypt, such a dense swarm of locusts as had never been before, nor ever shall be again. 15 They covered the surface of the whole land, so that the land was black; and they ate all the plants in the land and all the fruit of the trees that the hail had left; nothing green was left, no tree, no plant in the field, in all the land of Egypt. 16 Pharaoh hurriedly summoned Moses and Aaron and said, “I have sinned against the LORD your God, and against you. 17 Do forgive my sin just this once, and pray to the LORD your God that at the least he remove this deadly thing from me.” 18 So he went out from Pharaoh and prayed to the LORD. 19 The LORD changed the wind into a very strong west wind, which lifted the locusts and drove them into the Red Sea;1 not a single locust was left in all the country of Egypt. 20 But the LORD hardened Pharaoh’s heart, and he would not let the Israelites go.

Previous signs have impacted the prosperity of Egypt in significant ways: the livestock were diseased and died, the hail destroyed the flax and barley harvest (as well as any remaining animals in the field and servants), but now the remaining harvest for the year is wiped out. Yet, even with the loss of a complete harvest Egypt probably had the means to survive agriculturally because of the provisions set in place to deal with a famine. Genesis 41 narrates Joseph’s rise to power but also the consolidation of harvesting in centralized granaries to prepare for famine. If these granaries are in place, which the narrative seems to indicate, the people could still survive even the loss of a complete harvest. Yet, this is not to minimize the harshness of a farmer losing the production of their land for an entire year or the impact the individual people of Egypt would have felt in the midst of these signs. Yet, there is also a restraint even here as the pressure has been applied to force Pharaoh to let the people of Israel go. The picture of agricultural and environmental devastation is intense as the signs have progressed, and yet the LORD has continually provided a way for both the people of Israel and Egypt to continue.

This sign also has several points of resonance with the crossing of the Red (or Reed) Sea. Both here and in Exodus fourteen the sign begins with a strong east wind which blows all night which allows the locusts to come here and the sea to be parted later. Also the reverse wind, from the west, is used to get rid of the locusts and to return the sea to its banks after the people of Israel have passed. The link is strengthened by the locust being driven into the Red Sea. At a symbolic level there is also the possible poetic linking of Pharaoh and the people of Egypt with the locusts. They, in their oppression of the people of Israel, have been the ones who have consumed the produce of the productive land and who have transformed harvest into desolation. They too, like the locusts, will be thrown into the sea by the hardness in Pharaoh’s heart. Again, the LORD is the one who Exodus lifts up here as the one who is behind this hardening.

Exodus 10: 21-29- Darkness and the Defeat of Ra

21 Then the LORD said to Moses, “Stretch out your hand toward heaven so that there may be darkness over the land of Egypt, a darkness that can be felt.” 22 So Moses stretched out his hand toward heaven, and there was dense darkness in all the land of Egypt for three days. 23 People could not see one another, and for three days they could not move from where they were; but all the Israelites had light where they lived. 24 Then Pharaoh summoned Moses, and said, “Go, worship the LORD. Only your flocks and your herds shall remain behind. Even your children may go with you.” 25 But Moses said, “You must also let us have sacrifices and burnt offerings to sacrifice to the LORD our God. 26 Our livestock also must go with us; not a hoof shall be left behind, for we must choose some of them for the worship of the LORD our God, and we will not know what to use to worship the LORD until we arrive there.” 27 But the LORD hardened Pharaoh’s heart, and he was unwilling to let them go. 28 Then Pharaoh said to him, “Get away from me! Take care that you do not see my face again, for on the day you see my face you shall die.” 29 Moses said, “Just as you say! I will never see your face again.”

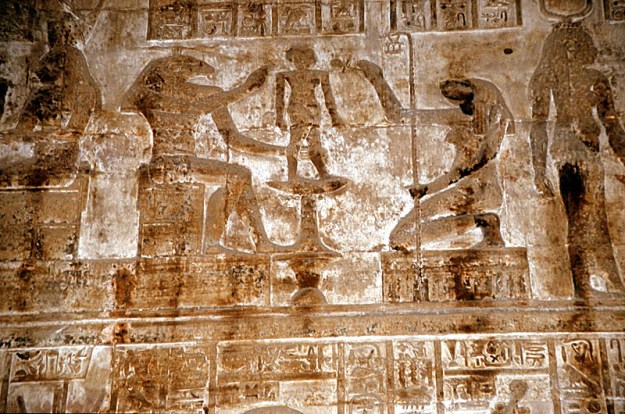

The tangible darkness, darkness that can be felt may seem like a strange penultimate sign until you consider that this is not merely a battle between Moses and Pharaoh. At its heart this is a conflict between the gods of Egypt and their emissary, Pharaoh, and the LORD the God of Israel. Ra, the god of the sun in Egyptian mythology, was the central god in the Egyptian pantheon. Earlier chapter seven I mentioned the strange uses of the word tannin for snake (tannin is typically a word for dragon or a chaos monster) and I alluded to the Egyptian myth of Ra entering into a nightly battle with Apep (the snake like evil force of chaos) who attempts to consume Ra and the sun each night in the underworld. Many of the Pharaoh’s even took the name Ramses (and the traditional Pharaoh viewed behind the narrative of the Exodus was Ramses II- whether the book of Exodus can be traced back to events in his reign ultimately is something that will likely never be proved). Pharaoh, the son of Ra, here would see the chief god of the pantheon and the authorizer of his reign blotted out for three days until the LORD relents. The future commandment that the people shall have no other gods before the LORD goes back to this time where the LORD in bringing the people out of Egypt demonstrated his power over the gods of Egypt.

Pharaoh again attempts to maintain control in his demonstrated weakness. Here men, women and children are free to go but the flocks must remain behind. There is a narrative logic to the Egyptians wanting the Israelites to leave their flocks behind as they depart to worship. Remember the Egyptians flocks were wiped out by disease and the hailstorm and even thought the Egyptians in Genesis and here seem to prefer cattle to sheep and goats in a desperate situation it would make sense to retain the herds. That being said, in the narrative it is also about coercion and power and ensuring the people would return to servitude. Pharaoh is still not willing to let the people go from their slavery or to imagine a new system without the Hebrews enslaved.