Psalm 108

A Song. A Psalm of David.

1My heart is steadfast, O God, my heart is steadfast; I will sing and make melody. Awake, my soul!

2Awake, O harp and lyre! I will awake the dawn.

3I will give thanks to you, O LORD, among the peoples, and I will sing praises to you among the nations.

4For your steadfast love is higher than the heavens, and your faithfulness reaches to the clouds.

5Be exalted, O God, above the heavens, and let your glory be over all the earth.

6Give victory with your right hand, and answer me, so that those whom you love may be rescued.

7God has promised in his sanctuary: “With exultation I will divide up Shechem, and portion out the Vale of Succoth.

8Gilead is mine; Manasseh is mine; Ephraim is my helmet; Judah is my scepter.

9Moab is my washbasin; on Edom I hurl my shoe; over Philistia I shout in triumph.”

10Who will bring me to the fortified city? Who will lead me to Edom?

11Have you not rejected us, O God? You do not go out, O God, with our armies.

12O grant us help against the foe, for human help is worthless.

13With God we shall do valiantly; it is he who will tread down our foes.

Psalm 108 brings together portions of two psalms attributed to David for a new time. Most interpreters believe that Psalm 57: 7-11 and Psalm 60: 5-12 were written before they were later joined together in the current psalm. This is a common practice in scripture where a key idea or phrase is utilized in multiple contexts[1] but here the entirety of the psalm is a composition of two previous psalms. Psalm 57: 7-11 forms the initial five verses while Psalm 60: 5-12 forms the final eight verses. Based on the position of Psalm 108 in book five of the Psalter the new situation may involve the return of the people to their home after the exile, but even without knowing a concrete situation for the invocation of these words from earlier psalms it points to the long-standing resonance and vitality of these words in the life of the people.

The heart (the organ of will in Hebrew) is steadfast and the proper response to the steadfast love of God is for the entirety of one’s being to respond in praise and song. The steadfast love (hesed) and the faithfulness of God are beyond measure and the psalmist’s gift of song echoes the chorus of a grateful creation to its creator. The joyous ending of Psalm 57 introduces the petition of verse six which initiates the quotation of Psalm 60.

The psalms are spoken from the embodied experience of the covenant people, and that experience involves times where God’s promise and presence feel distant. The beloved ones of God have always understood their continued existence was contingent on God’s continual provision. As in a previous time the people do not need a stronger army or a better military technology, they need the God who reigns over both Israel and the surrounding nations, to come to their aid. As J. Clinton McCann Jr. can articulate.

Their prayer is not that of the powerful, who seek to claim God’s sanction of the status quo. Rather, their prayer is the desperate prayer of those who turn to God as the only possible hope in an apparently hopeless situation (v. 11) (NIB IV:918)

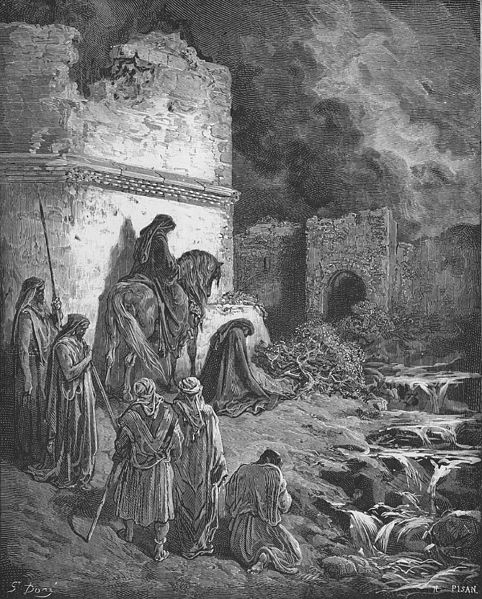

If these words reemerge in the fragile situation of the post-exilic return to Jerusalem where the people are threatened by hostile neighbors, the reminder that Moab, Edom, and Philistia are all under God’s claim[2] is a source of comfort. Yet, the people who claim the title of ‘those whom you love’ now feel the abandonment of God. God no longer goes out with the people or defends them, but they cry out to God for God’s renewed favor.

The psalms understand the dependence of the people upon God’s continual provision but also speak eloquently about the perception of God’s absence. This psalm utilizes two previously utilized psalms to speak of the trust in God’s steadfast love and faithfulness in a time where they feel endangered by God’s absence. Yet, the perception of God’s distance causes the beloved ones of God to cry out to God for deliverance from their current distress. For they can do nothing on their own, but with God they shall do valiantly.

[1] For example, 1 Chronicles 16 brings together Psalm 105: 1-11 and Psalm 106: 35-36, of Isaiah 2: 2-4 is repeated in Micah 4: 2-3. There are numerous other examples of parallels.

[2] The designation of Moab as washbasin, Edom as a place where shoes are hurled, and Philistia as one that the LORD shouts in triumph over may be intended as an insult to these nations, but it also may simply be a way of designating that they too remain under God’s control. Moab, Edom, and Philistia all incur words of judgment in the prophets (Ezekiel 25, Jeremiah 47–48, Obadiah 12-13).