Lamentations 1 The Cry of Daughter Zion

Lamentations 2 Speaking up for Daughter Zion

Lamentations 3 The Cry of the Strong Man

Lamentations 1 The Cry of Daughter Zion

Lamentations 2 Speaking up for Daughter Zion

Lamentations 3 The Cry of the Strong Man

1Remember, O LORD, what has befallen us; look, and see our disgrace!

2Our inheritance has been turned over to strangers, our homes to aliens.

3We have become orphans, fatherless; our mothers are like widows.

4We must pay for the water we drink; the wood we get must be bought.

5With a yoke on our necks we are hard driven; we are weary, we are given no rest.

6We have made a pact with Egypt and Assyria, to get enough bread.

7Our ancestors sinned; they are no more, and we bear their iniquities.

8Slaves rule over us; there is no one to deliver us from their hand.

9We get our bread at the peril of our lives, because of the sword in the wilderness.

10Our skin is black as an oven from the scorching heat of famine.

11Women are raped in Zion, virgins in the towns of Judah.

12Princes are hung up by their hands; no respect is shown to the elders.

13Young men are compelled to grind, and boys stagger under loads of wood.

14The old men have left the city gate, the young men their music.

15The joy of our hearts has ceased; our dancing has been turned to mourning.

16The crown has fallen from our head; woe to us, for we have sinned!

17Because of this our hearts are sick, because of these things our eyes have grown dim:

18because of Mount Zion, which lies desolate; jackals prowl over it.

19But you, O LORD, reign forever; your throne endures to all generations.

20Why have you forgotten us completely? Why have you forsaken us these many days?

21Restore us to yourself, O LORD, that we may be restored; renew our days as of old —

22unless you have utterly rejected us, and are angry with us beyond measure.

This final poem of Lamentations is the shortest of the five poems that make up the book and it has several differences from the preceding poems. It is one third of the length of the first three poems and half the length of Lamentations four. It also drops the acrostic[1] form but maintains the twenty-two lines that acrostic poems maintain. Yet more significant than the change in form and length is the change in voice and addressee. Previously there have been strong individual voices: daughter Zion, the narrator and the strong man, but now the voice of the poem becomes the communal ‘we.’ God has been a subject of the previous poems but was rarely addressed, now God is the direct addressee of this final poem. God has been absent and closed off throughout this book and yet the poet refuses to give up on God’s countenance returning to consider the plight of the people and acting upon that plight.

Most modern people of faith are used ideas of God inherited from philosophy that refer to God being omnipresent, omniscient, and all powerful. Yet, Hebrew thought doesn’t move in these patterns, nor would they care about a God who was all powerful and all seeing but did not act upon their world. The God of the Hebrew Scriptures is not an unmoved mover but a passionate and responsive God who may turn away in anger but whose steadfast love is unending. Yet, in this moment the people have experienced a God who in anger chooses not to see, hear, or respond to the people. This final poem, now in the voice of the people, once again calls upon their God to look at their situation, to see their troubles and their disgrace, and to act. In many ways the poem is echoes the protest psalms[2] which call upon God to remember the people and to deliver them from their turmoil.

The initial chapters of Jeremiah[3] utilize the metaphor of marriage between God and Jerusalem/Judah/the people, an image that is also utilized in Ezekiel 16 and is implied in the personification of daughter Zion in the initial two chapters of Lamentations. Now the image is reversed in this world where the inheritance of the people has been turned over to strangers and their homes to aliens. In a world where the people of Jerusalem and Judah have become orphans, the LORD is the absent father who has left their mothers to be like widows. God has abandoned the role of protector and provider for the people. Now the people are finding themselves as orphans in a world where nothing is provided. Water and wood must be purchased with hard labor. The joyous memory of childhood is forgotten under the hard labor and long days of their current bondage.

In verse six the people look in retrospect at the past alliances that they utilized to get the food they needed. They have relied upon Egypt and Assyria both for trade and for protection rather than trusting in their God. This reliance on God instead of military might, alliances, trade, and wealth has been a consistent theme in the law and the prophets but also was probably viewed as a naïve and unrealistic approach by many leaders of Israel and Judah. Yet, the poet looks upon the compromises of the past as evidence of the infidelity of the people to the LORD. They went to Egypt and Assyria to get bread in the past because they either did not fully rely on the LORD or were unfaithful to the covenant and therefore under judgment. By the time of Lamentations, Assyria was no longer a power in the world. Egypt continued to be relied on, even though they proved unreliable at the critical moment, by Judah until the collapse of Jerusalem. As the poet tries to make sense of the community’s current reality they look back to the sins of the past to explain the suffering of the present.

The poem describes an unsafe world that the people of Jerusalem now endure. The references may be to the time of the siege of Jerusalem or the entry into exile under Babylon. If the poem refers to the time of the siege of Jerusalem, the slaves that ruled over the people would come from Jerusalem. These would be the leaders left after the initial exile of leaders in 593 BCE when the Babylonians brought the king, many of the nobles and priests, and the best of the nation into Babylon. This is the background of the narrative beginning of the book of Daniel and the place where Ezekiel’s prophecies emerge from. Another alternative is that the ‘slaves’ are the servants of Nebuchadrezzar and the taskmasters who oversaw the removal of the people of Judah to their exile in Babylon. The witnesses of the siege of Jerusalem and the aftermath of the collapse both point to a treacherous time for the people. Providing for the daily needs of an individual or family in this chaotic time may have been a dangerous business. I’m reminded of the situation in Bosnia before U.N. Peacekeepers attempted to provide some stability, where men and women had to risk sniper fire to go to get groceries. Armed violent men could make even the simplest situations perilous. As mentioned in the previous poem, the nobles who had previously avoided having sunburned skin from working outdoors now have their fairer skin blackened by the sun and their fatness reduced by famine. Women are often the victims in times of conflict, and the poem does not shy away from the rape of both virgins and married women.

Elders and princes do not escape the punishment by the newly powerful ones. Being hung up by the hands is a form of torture and humiliation. It is probably not crucifixion, since that seems to emerge from the Persian empire, nor strappado which was a medieval punishment where the person is suspended by their hands being tied behind their back, used famously in Vietnam as a punishment for captured prisoners of war. Young men and old men both suffer in this moment. Young men carry the millstone, and the word for millstone (tehon) used here is not one of the regular words for this. A household millstone would be something a normal young man could easily bear, but perhaps this is something larger, and likewise carrying wood is something boys can do unless these are loads too heavy to bear. It is possible that these young men and boys are being asked to carry the loads that pack animals would normally carry and are being crushed under an unbearable weight. (Goldingay, 2022, p. 201)

The old men and the young men have ceased their normal activities. The music of the young and the gathering at the city gate by the old are now gone. The poem may intentionally echo the ceasing (NRSV are no more) of verse seven to indicate that the reason the music and gathering no loner happen is that the men are gone, they died in the conflict and the initial exile. Death hangs over the people and the remnant likely feel like they are ghosts of their former selves. They are heart sick, and their eyes have dimmed in their despair. Mount Zion, which they believed was established forever, is now the haunt of jackals.

The crisis for the people is the LORD’s inaction. They do not believe that the LORD is incapable of addressing their situation but rather that the LORD has forgotten and forsaken the people. The protest of this poet and the people lead them to cry to their God for restoration. Restore us, O LORD, that we may be restored. But the poem, and this collection of poems, ends surprisingly with a depressing possibility: the LORD has utterly rejected the people, and God whose steadfast love has always been stronger than God’s wrath is now angry beyond measure. The poet, based on the current situation of the people, holds this closing thought as a plausible reality. That they now live in a world where God has permanently turned away, where their prayers will never again be heard, when they will never again be the people of the LORD. It is almost like the poem ends with a shrug. If this is the way, then the orphaned people will have to learn how to live in the absence of their father. If the sins of their ancestors are unforgivable then they will have to learn to live in this dangerous world as the unforgiven.

Lamentations is an uncomfortable book. As Kathleen O’Connor eloquently states about the divine absence in the book:

There is only the blind God, the missing voice that hovers over the entire book. Lamentations is about absence…The experience of divine absence, blindness, and imperviousness to human suffering, expressed in countless ways by several speakers, is the book’s central subject. It is God’s absence from the poems, however, that creates space for the speakers to explore their momentous suffering, to move from numb silence and pre-literate groans to speech that is eloquent, beautiful and evocative and that gives form and shape to the unspeakable. (NIB VI: 1071)

The perception of God’s absence in moments of great suffering is a common experience in both individual and communal sufferings. The scriptures, particularly the Hebrew Scriptures, wrestle and protest God’s apparent absence at critical moments in the stories of the people and individual faithful ones. Lamentations voices a “daring, momentous honesty about the One who hides behind clouds, turns away prayers, and will not pay attention.” (NIB VI:1071) This is an audacious protest to God and is a model of a faithful poet, or poets, attempting to make sense of their place in a world where God seems absent and unwilling to see or hear.

Lamentations is one voice in the collection of voices that make up our scriptures. It is a voice from a time where the poet’s world has collapsed, and God appears absent. Yael Ziegler suggests that the book of Isaiah intentionally adopts some of the language of Lamentations to provide a new vision of hope for the people who survived the exile. (Ziegler, 2021, p. 478) Although the poems of Lamentations come to an end, the people who preserved these poems did not. There would be a time of renewed hope and a new beginning beyond this time of tragedy and heartbreak. Yet, they had to grieve before a new hope could be born. They would encounter this time of God’s wrath, silence, and abandonment before they would encounter a time where God would do a new thing in their midst. The book of Lamentations attempts to use words and structure to bring meaning and order to their grief and suffering. The reality that the community would continue to hand on these poems and later generations would continue to hold them as a part of their sacred writings even as God remains silent throughout the book testifies to their resonance with suffers from many generations.

[1] Acrostic poetry begins each line with a successive letter of the Hebrew alphabet.

[2] Psalm 44; 74; 79.

[3] Particularly Jeremiah 2-4.

A prayer of one afflicted, when faint and pleading before the LORD.

1Hear my prayer, O LORD; let my cry come to you.

2Do not hide your face from me in the day of my distress. Incline your ear to me; answer me speedily in the day when I call.

3For my days pass away like smoke, and my bones burn like a furnace.

4My heart is stricken and withered like grass; I am too wasted to eat my bread.

5Because of my loud groaning my bones cling to my skin.

6I am like an owl of the wilderness, like a little owl of the waste places.

7I lie awake; I am like a lonely bird on the housetop.

8All day long my enemies taunt me; those who deride me use my name for a curse.

9For I eat ashes like bread, and mingle tears with my drink,

10because of your indignation and anger; for you have lifted me up and thrown me aside.

11My days are like an evening shadow; I wither away like grass.

12But you, O LORD, are enthroned forever; your name endures to all generations.

13You will rise up and have compassion on Zion, for it is time to favor it; the appointed time has come.

14For your servants hold its stones dear, and have pity on its dust.

15The nations will fear the name of the LORD, and all the kings of the earth your glory.

16For the LORD will build up Zion; he will appear in his glory.

17He will regard the prayer of the destitute, and will not despise their prayer.

18Let this be recorded for a generation to come, so that a people yet unborn may praise the LORD:

19that he looked down from his holy height, from heaven the LORD looked at the earth,

20to hear the groans of the prisoners, to set free those who were doomed to die;

21so that the name of the LORD may be declared in Zion, and his praise in Jerusalem,

22when peoples gather together, and kingdoms, to worship the LORD.

23He has broken my strength in midcourse; he has shortened my days.

24“O my God,” I say, “do not take me away at the midpoint of my life, you whose years endure throughout all generations.”

25Long ago you laid the foundation of the earth, and the heavens are the work of your hands.

26They will perish, but you endure; they will all wear out like a garment. You change them like clothing, and they pass away;

27but you are the same, and your years have no end.

28The children of your servants shall live secure; their offspring shall be established in your presence.

Psalm 102 is described in its superscription as a prayer of one afflicted, when faint and pleading before the LORD. This type of description is unusual among the psalms. It doesn’t indicate an author to attribute the psalm to, nor does it give instructions for its performance or a reference to a scriptural story that the psalm comes from. This psalm of a suffering one who is alienated from their body, from society, and ultimately from God may have been intended as a psalm that any suffering individual could recite at times where their situation seemed hopeless, and God’s help seemed far away. Imagery of impermanence, loneliness, pain, and shame permeate the complaint of the psalm, but like many psalms of complaint there is a turn towards hope. The psalmist intuits that the answer, “to human finitude and mortality is divine infinitude and immortality.” (Nancy deClaisse-Walford, 2014, p. 754)

The opening language of the psalm resonates with appeals throughout the psalter as Rolf A. Jacobson notes:

The opening appeal to be heard employs language quite typical of these entreaties—hear my prayer, let my cry come unto you (39:12), do not hide your face (27:9; 143:7), turn your ear towards me (31:2; 71:2), make haste to answer me (69:17; 143:7) (Nancy deClaisse-Walford, 2014, p. 751)

Although Rolf Jacobson attributes this to intentionally creating a generic composition for use in the community, the use of familiar language may also reflect a person shaped in the communal worship which utilizes these psalms. The language of prayer and faith is shaped in the worshipping community which shaped the psalmist’s faith and life. Yet, now in a time when the author is alienated from their own physical body, from the community, and from God, they turn to the words that shaped their life when they were physically, socially, and religiously whole.

The psalm moves between personal complaints about their own health and isolation, “I complaints” in Westermann’s terminology, complaints about the actions of isolation and persecution by those in the psalmist’s society, “they complaints”, and complaints about the way that God is treating the psalmist, “you complaints.”[1] The personal complaints begin with an image of transience that reminds me of Ecclesiastes frequently used term hebel (vanity, emptiness). Hebel literally means smoke, mist, or vapor but is often used metaphorically to refer to the emptiness of life.[2] Now for the psalmist their days pass away like smoke and their bones burn like a furnace. Their life down to their very bones is going up in smoke while their heart withers like grass and they are too far gone to even eat the bread that could give them strength. Their songs have turned to groans and their body now is transforming into a (barely) living skeleton. We don’t know if they were suffering from an illness, but they attribute their suffering to God’s judgment upon them. Their suffering is also done in isolation, they are like an unclean owl of the wastelands or a lonely bird on a roof. These lonely images of birds heighten the feeling of the psalm, for the sufferer is not only weak but they are abandoned.

The social complaints are also sharply worded as the psalmist’s unnamed name is synonymous with a curse among their enemies. Their personal weakness and isolation are viewed in the society as a curse from God, and enemies have taken advantage of this weakness. The only nourishment left for this abandoned one is the bread of ashes and the drink of tears. Yet, behind both the physical pain and suffering and the social isolation is the LORD. We are never told of any sin that this poet has committed, but they view their suffering because of God’s anger and distance. In the words of the psalm God has cast the suffering one aside and yet hope resides in God repenting from God’s attitude towards the psalmist, turning the face and hearing with the ear and responding with grace and healing.

In contrast to the evanescent position of the psalmist is the strength and might of the LORD. The psalmist now joins his fate to the action of God to have compassion on Zion. It is possible that this psalm originates in the time of the exile where there is hope for the rebuilding of Zion and rescue the people from the destitute position as exiles in a foreign land. Yet, even without the context of the Babylonian exile, the turn to hope is based on the faithfulness of God for the people and a belief that God’s anger lasts only a moment, but God’s favor is for a lifetime.[3] The poet’s strength may have been broken in the middle of their life by God’s action, but if God wills it will be renewed. The heavens and the earth which seem so permanent to humanity are like a garment that can easily be changed by the powerful and permanent God. God will continue to endure and only in God can this suffering one hope to find a renewed physical, social, and religious life. The psalmist claims their familial bond to the LORD the God of Israel and now awaits the parental turning of their God to the children of God’s servants.

[1] Rolf A. Jacobson notes this helpful pattern citing Westermann, The Psalms (54-57). (Nancy deClaisse-Walford, 2014, p. 752)

[2] Psalm102 does not use the term hebel but the combination of words of impermanence create a similar resonance for me as Ecclesiastes.

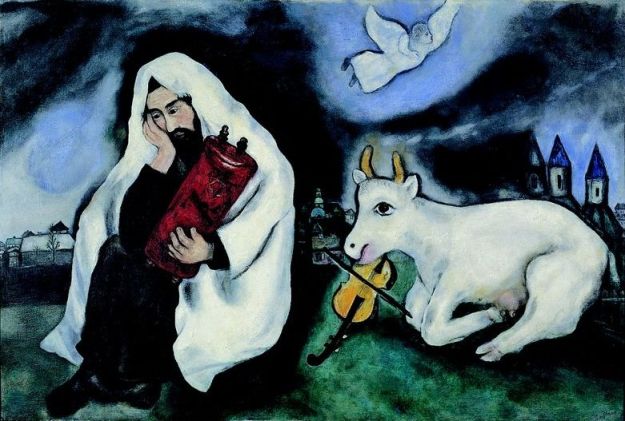

Marc Chagall, Solitude (1933)

<A Song. A Psalm of the Korahites. To the leader: according to Mahalath Leannoth. A Maskil of Heman the Ezrahite.>

1 O LORD, God of my salvation, when, at night, I cry out in your presence,

2 let my prayer come before you; incline your ear to my cry.

3 For my soul is full of troubles, and my life draws near to Sheol.

4 I am counted among those who go down to the Pit; I am like those who have no help,

5 like those forsaken among the dead, like the slain that lie in the grave, like those whom you remember no more, for they are cut off from your hand.

6 You have put me in the depths of the Pit, in the regions dark and deep.

7 Your wrath lies heavy upon me, and you overwhelm me with all your waves. Selah

8 You have caused my companions to shun me; you have made me a thing of horror to them. I am shut in so that I cannot escape;

9 my eye grows dim through sorrow. Every day I call on you, O LORD; I spread out my hands to you.

10 Do you work wonders for the dead? Do the shades rise up to praise you? Selah

11 Is your steadfast love declared in the grave, or your faithfulness in Abaddon?

12 Are your wonders known in the darkness, or your saving help in the land of forgetfulness?

13 But I, O LORD, cry out to you; in the morning my prayer comes before you.

14 O LORD, why do you cast me off? Why do you hide your face from me?

15 Wretched and close to death from my youth up, I suffer your terrors; I am desperate.

16 Your wrath has swept over me; your dread assaults destroy me.

17 They surround me like a flood all day long; from all sides they close in on me.

18 You have caused friend and neighbor to shun me; my companions are in darkness.

Psalms 88 and 89 stand together at the end of book three of the book of Psalms and take us into the darkest despair of the entire book. (Nancy de Claisse-Walford, 2014, p. 668) Both prayers are appeals for help that have no resolution within the psalm and while Psalm 89 is a prayer grieving the destruction of Judah and the loss of the promises to the line of David, Psalm 88 is the prayer of an individual who is either metaphorically or physically at the point where, “Death is so near and so real that it becomes the subject of the lament.” (Mays, 1994, p. 282) This is not the type of prayer that was taught in Sunday school, nor is this psalm used in the worship of most churches. Its vision of the world is darker than many churches are comfortable with but it also speaks honestly to the experience of deep darkness that many both inside and outside the church experience. The daring language of the psalm, which is willing to declare that God is responsible for their dire circumstance, turns on the head the vision of Psalm 56:4 or Romans 8:31 as it wonders, “if God is against me, who can be for me?” The psalmist’s words break forth from the dark night of the soul where their abandonment by God and their companions leaves only darkness to know them.

The psalm is attributed to Heman the Ezrahite. It is possible that the intent is to attribute the psalm to Heman who is listed as one of the wise men who Solomon surpasses in 1 Kings 4:31 or Heman the singer, one of the Kohathites appointed by David in 1 Chronicles 6:33. It is also possible that it is the same individual referred to in both 1 Kings and 1 Chronicles (singers/psalmists would be considered wise in Hebrew society) but it is also likely that the Heman referred to in the psalm is a different person unmentioned elsewhere in scripture. Regardless of the authorship of the psalm, it speaks in the brutally honest language of the Hebrew Scriptures that many contemporary Christians have little exposure to.

The psalm begins in a pious cry out to God, crying out to God for God’s attention to the prayers of the one dependent on God’s salvation. The prayer uses three different words for ‘crying out’ to God in verse 1, 9b and 13 (NIB IV: 1027) exhausting the language of prayer as they desperately seek an answer from the God who is both their only hope of salvation and the source of their troubles. The psalm begins with language that would is the traditional language of prayer learned in worship. Yet, once the prayer begins the dam holding back the psalmist’s words breaks and their desperation and abandonment cannot be contained. The pain of the psalmist rushes forth from the shattered walls of convention and flows into an irresistibly honest prayer that emerges from the space of death, darkness, and despair.

The stakes of this prayer are incredibly high for the psalmist. The very center of their life[1] is threatened. The psalmist deploys an incredible number of words for death: Sheol, the Pit, like the dead, slain, grave, those you remember no more, cut off from your hands, in the regions dark and deep, shades (Hebrew Rephaim), Abaddon, darkness, the land of forgetfulness. Almost every line has the presence of death within this prayer. This deployment is especially striking when compared to the rest of the Hebrew Scriptures which rarely talk about death and the afterlife. In verses three to five the mentions of death indicate the serious nature of the psalmist’s petitions but the jarring realization comes in verse six when the psalmist turns their invective to God and declares that God is the one responsible for the psalmist’s situation. God may be the psalmist’s salvation but God is also, in this psalm, the psalmist’s oppressor.

The psalmist girds up their loins and stands before God in accusation declaring that God has put them at death’s door, that God’s wrath is actively overwhelming the psalmist in waves, and God has caused the alienation of the psalmist from their companions. Many Christians are not familiar with this type of accusatory language directed at God and are surprised at the directness of this psalm or Jeremiah’s accusations of God.[2] As mentioned in my comments on Psalm 86 there is a relationship between the servant and their Lord, and here the servant boldly claims that their Lord has violated their relationship. Where the servant needed protection, their Lord has overwhelmed them with wrath. Where the servant looks for a compassionate answer, the answer[3] they receive is unbearable. The actions of God have alienated the servant from both God and their companions making them, like Job, one despised and one cursed by God.

The psalmist’s eyes growing dim is not a statement of eyesight, but indicates that their vitality is failing. Physically and mentally, they are dying and yet they continue to cry out to God. They cry out from a place of “abandonment and lostness…so great that it saturates the soul so there is room for nothing else.” (Nancy de Claisse-Walford, 2014, p. 671) But it is heartbreaking that for the psalmist it is God who has cast them into this space of darkness and death and then turns away from their cries. In a series of six rhetorical questions: Do you work wonders for the dead? Do the shades rise up to praise you? Are your wonders known in the darkness, or your saving help in the land of forgetfulness? Is your steadfast love declared in the grave, or your faithfulness in Abaddon? The answer to each of these rhetorical questions in the vision of the psalmist is no! As mentioned above the Hebrew scriptures rarely talk about death and the afterlife and there is no conception of heaven and hell as destinations for the people of God in the psalms. Psalm 88 deploys this shocking set of questions to the God of life to get their either unresponsive or oppressive God to relent and deliver their servant from death or the relationship will be broken and God will be the unfaithful one who broke it. In the Psalms when the concept of death, Sheol, the Pit, or Abaddon are mentioned it is assumed that there is no longer any communication between the deceased and God.[4] The only freedom this psalm offers the psalmist is the freedom of the dead where God either does not remember or has actively cut off God’s servant. (Nancy de Claisse-Walford, 2014, p. 671) Yet the psalmist cries out to their Lord as a servant desiring to continue to serve their God in the land of the living.

The psalmist cries out one final time in verse thirteen. Their prayers come before God and even boldly confront[5] God asking God to relent. God’s anger has left the psalmist in the space of darkness and death. There is no escape for the servant from the anxiety filled and deathly state of the servant’s life. There is no answer as the psalm reaches its final gasp, there is only the cry of the servant thrown “against a dark and terrifying void” (Nancy de Claisse-Walford, 2014, p. 669) The final word of the psalm is darkness.[6] The sad final phrase is obscured by the NRSV’s translation. The NIV’s “darkness is my closest friend” or Beth Tanner’s “only darkness knows me” (Nancy de Claisse-Walford, 2014, p. 670) better captures the isolation and abandonment that the psalm closes with. We may rebel against a psalm where death and darkness have the final word, but the book of Psalms reminds us that there are times where the faithful ones of God may find themselves in the God forsaken place where God seems silent, absent, or angry; where relationships prove themselves unfaithful, and where the agonizing prayer breaks forth to God from the death’s door where no light seems to be able to penetrate the darkness of the faithful one’s world.

Nobody would choose to walk into the place of depression and suffering where death and darkness seem to be their only companion, but even people of faith may find themselves in these spaces that appear devoid of God’s steadfast love and compassion. Depression can make the world feel like a place where darkness is the sufferer’s only companion and death may cry out to them. Even faithful people can suffer from bouts of depression so deep that suicide and death seem closer than God. God does not condemn these words of the psalmist as faithless, instead they are placed within the scriptures of God’s people. From a Christian perspective we may answer the rhetorical questions of Psalm 68 differently than the psalmist: from a Christian perspective, to quote Paul, “If we live, we live to the Lord, and if we die, we die to the Lord; so then, whether we live or whether we die, we are the Lord’s.” (Romans 14:8) Yet, this psalm invites us to walk into the swampland of the soul, pitch a tent, and get to know the lay of the land. It invites us to dwell in the God forsaken place of the crucifixion without immediately jumping forward to the surprise of the resurrection. Sometimes resurrection takes time, sometimes prayers end in darkness as they await a response from God, and sometimes faithful ones walk through the valley of the shadow of death. This uncomfortable psalm invites us into an honest relationship with God that demonstrates a confrontational or defiant calling upon God to act in compassion and love rather than abandonment or wrath. We may not like that darkness has the last word and we may want a happy ending to occur within eighteen verses, but sometimes we dwell in darkness and hope for a light which we cannot see but our faith longs for.

[1] The NRSV’s ‘soul’ in verse 3 is the Hebrew nephesh which occurs frequently in the psalms but the modern idea of ‘soul’ comes from Greek thought instead of Hebrew thought. The Hebrew nephesh is closer to ‘life itself’ or ‘the essence of life.’

[2] For example: Jeremiah 15: 17-18, 20: 7-10. Particularly in Jeremiah 20 our English translations often soften the shocking language or Jeremiah.

[3] The Hebrew word translated ‘waves’ also can means ‘answer.’

[4] See for example Psalm 6:5, Psalm 30:9. The contrary point will be argued by Psalm 139:8 where even if the psalmist makes their bed in Sheol, God is present there.

[5] The Hebrew verb qdm can mean either come before or confront.

[6] The final word of the psalm is the Hebrew hoshek (darkness).

Margaret Adams Parker, Reconciliation: Sculpture of the Parable of the Prodigal Son for Duke Divinity School (2005) View 1

Margaret Adams Parker, Reconciliation: Sculpture of the Parable of the Prodigal Son for Duke Divinity School (2005) View 2

You stand out on the crossroads looking for the prodigal

Waiting for the return of the one who cashed in his heritage

Who took what we worked so long to build and walked away

He wished for your death and plundered your house

And yet day after day you wait for his return, this lost son

Like some wandering sheep you set out in search of him

Like some lost coin you search every corner to find again

And so, you stand out at the crossroads today and every day

While I rise up in your stead, tending the flock, sowing the seed

Working to ensure that for all of us there will be a harvest

You pine for your lost son, I grieve for my lost father

This son of yours, this spoiled younger brother of mine

Unwilling to dirty his hands among the fields or to care for the home

Who shirked the yoke that I bore for you countless seasons

There were always excuses that were made on his behalf

I thought that his last request might finally cross a line

That this final insult, this slap in the face might raise your ire

Is there nothing he could do, no request he might make

That might cause you to put your foot down and say, ‘no more’

How could you let him take away the work of our hands

Going off to a distant land with the wealth of generations

This son of yours, this spoiled younger brother of mine

The days you spent on the crossroads looking for the prodigal

Are the days you never once looked at me managing the house

Sweating with the servants in the field to sow and reap a harvest for you

Holding everything together while you stayed lost in your grief

Did your eyes never fall upon me as I shepherded your flock?

Was a word of praise ever uttered from your lips for my longstanding obedience?

Did your desire to see what was lost blind you to what remains?

The absent son who erased the son with calloused hands and burnt skin

Who stayed and never strayed from the homestead

And who is still waiting here for you to join him as he works in the vineyard

Then, one day, as I exit the fields at the end of a weary day

I hear merriment as the town eats our food and drinks our wine

The fatted calf has been slaughtered for the prodigals return

And while the entire town was invited to the celebration

You never considered coming to the fields to retrieve me?

It is only from a slave that I learn that my brother has returned

And my father as well, back from the crossroads and the ends of the earth

You rejoice with the town while my soul bleeds outside the home I sustained

What must I do to be seen, heard, loved and welcomed?

Must I also become the prodigal for you to celebrate me?

Must I deny you so that you might accept me?

How long before you realize that there is a son missing from your feast?

Before you make the journey into the fields you abandoned for the crossroads?

Until you see the son who didn’t squander your wealth with prostitutes

He feasted away your fortune and you throw him a feast of rich foods

I worked your fields, maintained your table, fed your flocks

Yet, not even a goat was to be spared for me and my friends

Welcome home father, I hope you appreciate the pantry I stocked

Welcome home brother, I hope you enjoyed the calf I raised

Hear this lament of the forgotten son who awaited your return

To the family you both turned your backs upon

Psalm 31

To the leader. A Psalm of David.

1 In you, O LORD, I seek refuge; do not let me ever be put to shame; in your righteousness deliver me.

2 Incline your ear to me; rescue me speedily. Be a rock of refuge for me, a strong fortress to save me.

3 You are indeed my rock and my fortress; for your name’s sake lead me and guide me,

4 take me out of the net that is hidden for me, for you are my refuge.

5 Into your hand I commit my spirit; you have redeemed me, O LORD, faithful God.

6 You hate those who pay regard to worthless idols, but I trust in the LORD.

7 I will exult and rejoice in your steadfast love, because you have seen my affliction; you have taken heed of my adversities,

8 and have not delivered me into the hand of the enemy; you have set my feet in a broad place.

9 Be gracious to me, O LORD, for I am in distress; my eye wastes away from grief, my soul and body also.

10 For my life is spent with sorrow, and my years with sighing; my strength fails because of my misery, and my bones waste away.

11 I am the scorn of all my adversaries, a horror to my neighbors, an object of dread to my acquaintances; those who see me in the street flee from me.

12 I have passed out of mind like one who is dead; I have become like a broken vessel.

13 For I hear the whispering of many — terror all around! — as they scheme together against me, as they plot to take my life.

14 But I trust in you, O LORD; I say, “You are my God.”

15 My times are in your hand; deliver me from the hand of my enemies and persecutors.

16 Let your face shine upon your servant; save me in your steadfast love.

17 Do not let me be put to shame, O LORD, for I call on you; let the wicked be put to shame; let them go dumbfounded to Sheol.

18 Let the lying lips be stilled that speak insolently against the righteous with pride and contempt.

19 O how abundant is your goodness that you have laid up for those who fear you, and accomplished for those who take refuge in you, in the sight of everyone!

20 In the shelter of your presence you hide them from human plots; you hold them safe under your shelter from contentious tongues.

21 Blessed be the LORD, for he has wondrously shown his steadfast love to me when I was beset as a city under siege.

22 I had said in my alarm, “I am driven far from your sight.” But you heard my supplications when I cried out to you for help.

23 Love the LORD, all you his saints. The LORD preserves the faithful, but abundantly repays the one who acts haughtily.

24 Be strong, and let your heart take courage, all you who wait for the LORD.

If you are looking for a strong linear progression in the poetry of a Psalm, then this will not be the Psalm for you. Yet if you are willing to acknowledge that life and faith are rarely linear and that doubt and faith are often places which people in crisis oscillate between. If you can understand that a life of faith is a place where one calls upon the LORD and trusts in the LORD but then must inhabit the space of waiting on the LORD’s actions in the presence of enemies and persecutors who are seen and felt. Then Psalm 31 with its movement from crisis to trust to crisis to trust may be a Psalm that feels complete, honest and genuine to your experience.

Some people have wanted to break the Psalm into two separate Psalms based on the division between verse eight and nine where verses six through eight demonstrate a resolution and a trust in God and verse nine begins again in crisis which seems an even more intense. While the Psalm does have two progressions from crisis to trust and it makes sense to look at the two progressions within it, as I mentioned above life is rarely a nice linear progression from crisis to resolution. Faith and trust may be quickly followed by doubt and despair in the poet’s life. We do not know what type of crisis they are dealing with but there is this continual movement in the Psalmist’s words from the cry to the LORD in the midst of crisis where one asks for God to be the refuge or strength in their life back to the assurance of faith in who the LORD is to the petitioner.

The first four verses of the Psalm call upon God to be their refuge, the one who protects them from shame, their deliverer, their strong fortress and the one who delivers them from a trap. These are all familiar images for God. The Psalmist doesn’t ask for God’s action because of their own righteousness and honor but rather on the LORD’s righteousness and honor. The Psalmist is one who has trusted in the LORD and believes that God will deliver them from this crisis and those who seek to destroy their life and their reputation. Being put to shame, which the Psalmist asks the LORD to prevent, is not merely being embarrassed or humiliated but rather in an honor-shame based society it was to lose one’s standing in society. Dishonor in the ancient world would ruin a person’s name and often could lead to death or ‘a broken life of no hope.’ (Brueggeman, 2014, p. 157)

Verse 5 may sound familiar to many Christians because in Luke’s gospel these words are spoken by Jesus during the crucifixion (Luke 23:46). The Hebrew word for spirit (ruach) means wind, breath, or spirit (in the connotation of one’s life). In the Psalm itself the poet commits their life into God’s hands so that God may deliver them amid their crisis. In Luke’s gospel these words take on a slightly different tone because now Jesus is commending his life into the Father’s hands even as he lets go of life on the cross. The hope of the Psalmist is a hope of God’s deliverance within the span of their days, Christ calls upon God’s deliverance beyond the bounds of death.

For the Jewish people the LORD is one who sees and acts. From the foundational story of the Exodus through the remainder of the Hebrew Scriptures, the LORD is trusted in to hear, see and act for the one who is in oppression. The corporate trust of the people becomes the individual trust of the Psalmist. In this brief window into the faith of the poet in verses 6-8 we see the how the covenantal faith that they are a part of shapes their trust and expectations of their life with the LORD. Much like the green pastures and still waters of Psalm 23, the broad place of Psalm 31 is a place where the petitioner finds rest and renewal. Yet, this space of rest and renewal do not guarantee a future life free from persecution and trials.

By verse nine the language of distress returns, and it is expressed in language far more intense than originally present in the Psalm. One of the gifts of spending time with the Bible is the deep and sometimes raw honesty that can exist between God and God’s people. Jeremiah, for example, would bear God’s painful emotions to the people but would also use honesty to speak to God on behalf of the people and on behalf of his own experience. The Psalms are emotionally honest poetry, songs and prayers which don’t sanitize the experience of grief, joy, pain, disappointment, fear, distress, jubilation or regret when speaking to God. The Psalms, like all good poetry seeks to move beyond the rational part of our life and moves into the emotions that we must deal with. As Beth Tanner says

Poetry is meant to engage our memories and our imagination and in that transform our relationship with God, so the meaning of this psalm is to examine the thin line between faith and doubt that we all share as we strive to better understand and embrace our relationship with God. (Nancy deClaisse-Walford, 2014, p. 305)

The Psalmist prays for God to be the God who hears and sees and acts, like the God of the Exodus. The poet remembers the covenant and calls upon the LORD of Israel to intervene in their own struggles. The corporate faith becomes embodied in the individual struggles of faith and life. The life of the faithful one is not free of struggle and oppression, yet even in times of struggle the LORD the God of Israel is the one who the Psalmist places their trust in. The faithful one may question why God appears to not act on their behalf when they are being dishonored and threatened but they trust that their God do see, hear and act faithfully.

<To the leader: according to The Deer of the Dawn. A Psalm of David.>

1 My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? Why are you so far from helping me, from the words of my groaning?

2 O my God, I cry by day, but you do not answer; and by night, but find no rest.

3 Yet you are holy, enthroned on the praises of Israel.

4 In you our ancestors trusted; they trusted, and you delivered them.

5 To you they cried, and were saved; in you they trusted, and were not put to shame.

6 But I am a worm, and not human; scorned by others, and despised by the people.

7 All who see me mock at me; they make mouths at me, they shake their heads;

8 “Commit your cause to the LORD; let him deliver– let him rescue the one in whom he delights!”

9 Yet it was you who took me from the womb; you kept me safe on my mother’s breast.

10 On you I was cast from my birth, and since my mother bore me you have been my God.

11 Do not be far from me, for trouble is near and there is no one to help.

12 Many bulls encircle me, strong bulls of Bashan surround me;

13 they open wide their mouths at me, like a ravening and roaring lion.

14 I am poured out like water, and all my bones are out of joint; my heart is like wax; it is melted within my breast;

15 my mouth is dried up like a potsherd, and my tongue sticks to my jaws; you lay me in the dust of death.

16 For dogs are all around me; a company of evildoers encircles me. My hands and feet have shriveled;

17 I can count all my bones. They stare and gloat over me;

18 they divide my clothes among themselves, and for my clothing they cast lots.

19 But you, O LORD, do not be far away! O my help, come quickly to my aid!

20 Deliver my soul from the sword, my life from the power of the dog!

21 Save me from the mouth of the lion! From the horns of the wild oxen you have rescued me.

22 I will tell of your name to my brothers and sisters; in the midst of the congregation I will praise you:

23 You who fear the LORD, praise him! All you offspring of Jacob, glorify him; stand in awe of him, all you offspring of Israel!

24 For he did not despise or abhor the affliction of the afflicted; he did not hide his face from me, but heard when I cried to him.

25 From you comes my praise in the great congregation; my vows I will pay before those who fear him.

26 The poor shall eat and be satisfied; those who seek him shall praise the LORD. May your hearts live forever!

27 All the ends of the earth shall remember and turn to the LORD; and all the families of the nations shall worship before him.

28 For dominion belongs to the LORD, and he rules over the nations.

29 To him, indeed, shall all who sleep in the earth bow down; before him shall bow all who go down to the dust, and I shall live for him.

30 Posterity will serve him; future generations will be told about the Lord,

31 and proclaim his deliverance to a people yet unborn, saying that he has done it.

Psalm 22 echoes heavily in the gospel writer’s telling of the crucifixion of Jesus and it forms a central part of the liturgy of holy week (closing the Maundy Thursday service and serving as the pivot into Good Friday). For both Jewish and Christian readers this Psalm of suffering and lament has been a place that can reflect the reality of the faithful life when God seems absent and God’s promises not to forsake seem far away. Many people are troubled when they read the language of the Psalms of Lament, particularly the vivid language of Psalm 22 because it seems unlike the language of faith. Yet, here in the place of suffering where the faithful one calls out to God and questions God’s seeming lack of intervention is a faithful (even if difficult) place. As Beth Tanner can state, “Crying out in pain and expressing trust are not incompatible.” (Nancy deClaisse-Walford, 2014, p. 233) There will always be those, like Job’s friends in the book of Job, who want to equate suffering as proof of the suffering one’s unfaithfulness and demand a rigidly ordered world where the righteous prosper and the unrighteous are punished but the real world is seldom that tidy. My experience as well as my reading of the story of many of the saints of the church and the patriarchs and matriarchs of the Jewish story reveal a very different dynamic: frequently those saints and ancestors in the faith do suffer, and often in ways that seem unreasonable, yet they can hold their suffering within the framework of a world where God still remains sovereign even if the world is often incomprehensible.

The Psalm begins with a cry to a known God, the one the sufferer calls out to is their God who they have known in the past, who has been present and active throughout their lives and who now seems absent. It is this absence of God’s presence that makes a space for the crisis of the sufferer and allows their oppressors to have their way. For the petitioner who cries out to God they trust that God is a God who hears, much as in the Exodus when God heard the cries of the Israelites, and the Psalmist calls upon this history of God’s action in the past on their behalf and on behalf of the people. The Psalmist contrasts the position of their ancestors ‘who trusted in you and were not put to shame’ and their own experience of being despised and scorned. The Psalmist oscillates between the ways in which God has acted in the past and their own experience of abandonment, terror and shame. The poetic language of this Psalm is particularly rich in representing their opponents as wild bulls, ravening lions, a pack of vicious dogs and their experience takes a toll on their own body in vivid ways: mouth dried up like a potsherd, being poured out like water and bones being out of joint with a heart that has melted like wax, and they are dying of hunger to the point where their bones stand out against their skin. The person places their petition to God in the direst terms possible, their petition is a matter of life and death and their only hope is for God to hear and act like God has heard and acted in the past and to honor God’s promise not to forsake.

As with most of the Psalms of Lament, Psalm 22 allows us to see the reversal of the petitioner’s condition. In the middle of verse 21 the situation changes and the tone changes. The verse begins ‘save me from the mouth of the lions’ but then abruptly switches ‘from the horns of wild oxen you have rescued me’. We don’t know the time that elapses in this transition but the deliverance occurs and the prayer switches to one of praise. Since God has not despised or disdained, there is a hope for tomorrow. Those who sought the LORD now become those who praise, the poor whose bones could be counted can finally eat and be satisfied and the God who seemed to forsake has become the LORD who reigns over the nations. God’s action in the speaker’s generation ensures that another generation will be told about the God who watches over God’s faithful people and hears their complaints and prayers.

For the first tellers of the story of Jesus the resonant images of Psalm 22 probably helped to make sense of their experience of the crucifixion. For both Matthew and Mark the words Jesus speaks from the cross, “Eloi, Eloi lema sebachthani, my God, my God why have you forsaken me” would resonate with the beginning of this Psalm and the question of the righteous suffer. Even within the experience of that day where the soldiers cast lots for the garments of Jesus, the Psalm provides an easy connection for followers trying to make sense of the senseless suffering. The Psalms provided a language for their experience and words for their pain.

As important as Psalm 22 is for Christians in telling the story of the crucifixion both in scriptures and in the liturgy of Holy Week we cannot leave it only there. Psalm 22, and the psalms of lament more generally, are rich and powerful words that for generations of Jewish and Christians followers of God have given voice to a cry for deliverance. Whether it was the Jewish people in exile in Babylon, slaves crying out in suffering, or the person dealing with a devastating injury or illness that has robbed them of their sense of belonging we need to hear again that the God who we perceive has forsaken us can indeed hear our cry. We need to be able to claim that the experience of suffering and isolation need not be read as an implication of our own unfaithfulness or unrighteousness, but that indeed crying out to God in that time of suffering and isolation is itself a mighty cry of faith. Groaning words can indeed be powerful words when they reach the ears of the LORD who rules over the nations.

To the leader. A Psalm of David

1 How long, O LORD? Will you forget me forever?

How long will you hide your face from me?

2 How long must I bear pain in my soul,

and have sorrow in my heart all day long?

How long shall my enemy be exalted over me?

3 Consider and answer me, O LORD my God!

Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep the sleep of death,

4 and my enemy will say, “I have prevailed”;

my foes will rejoice because I am shaken.

5 But I trusted in your steadfast love;

my heart shall rejoice in your salvation.

6 I will sing to the LORD,

because he has dealt bountifully with me.

Psalm 13 is one of the examples used to talk about a Psalm of lament because it comes out of the experience of struggle and strife and calls upon God to act upon the crisis that the faithful one is experiencing. The crisis is not only a physical or emotional crisis but for the Psalmist, at its core, it is a theological crisis. The confident opening of the Psalter with Psalm 1 that sings about how the LORD watches over the righteous and the way of the wicked perishing is called into crisis by the moment of conflict where God seems to have forsaken the one lifting up this prayer. In the midst of the crisis the Psalmist cries out to the LORD and calls upon God to act.

This type of bold prayer, which calls upon God to act and to intervene, might seem unusual for many people. Many Christians were taught growing up that you didn’t accuse God or question God’s motives and that prayers were always to be polite and stoic. Although this view is common it has little to do with the Biblical model of prayer or the relationship of many of the faithful with God. Jeremiah, for example, makes numerous accusations towards God throughout the book of Jeremiah, Job also can cry out and expect God to act upon his complaints, and finally the Psalter is full of powerful, unfiltered emotions that are directed towards God and wrestle with the LORD who can bring about a resolution to the struggle. It takes courage to ‘gird up ones loins’ and stand before God in this manner, to be willing to accuse God in failing in God’s responsibility to maintain faithfulness and watchfulness as a covenant partner. The Psalmist views the relationship with God as pivotal for their life and if God turns God’s face away and removes God’s protection and allows the enemy to prosper and prevail then God is not fulfilling God’s part of the relationship. The Psalmist’s faith is strong enough to confront God that all is not right in God’s creation (Nancy deClaisse-Walford, 2014, p. 163) and that God is the responsible party to ensure that the righteous are protected and the wicked are punished.

How long, which is repeated four times in the first half of the Psalm is not asking for a time period but rather for an immediate intervention. It is a rhetorical device that is common in African-American preaching to increase the intensity of the expectation and hope that change is coming for the way things are cannot be sustained in a creation where the LORD is paying attention and is active. For example Martin Luther King, Jr. in his speech in Montgomery, Alabama on March 25, 1965:

How long? Not long, because no lie can live forever. How long? Not long, because you still reap what you sow. How long? Not long, because the arm of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice. How long? Not long, ‘cause mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.’ (Brueggemann, 2014, p. 79)

How long will the Psalmist continue to cry out to God before God answers? The hope is certainly not long. In the God forsaken place that the Psalmist cries from they know that only the enemy’s triumph and the sleep of death wait for them. They are at the end of the strength and the end of their resources and despair is coldly creeping into their soul, and yet in an act of defiance the call out to their God to act on their behalf, to fulfill God’s promises and to rescue the righteous one from the triumph of the wicked.

The Psalm ends with a note of trust or perhaps, as many commentators believe, the Psalmist has seen God’s answer to their prayer. If the prayer is answered we have no way to know how long elapses between verse four and the final statements in verses five and six. Perhaps they come hours, days, weeks or even years later when the Psalmist now stands in a place where God’s face continues to shine upon them. Yet, perhaps the ending is not a triumphal as a final answer but the whisper of trust into the deafening depression of despair. From my own experiences there can be this type of internal dialogue in that place of hopelessness where one struggles with and for one’s faith. One can boldly cry out to God and call upon God to act in the situation. Even in that space where all one perceives is isolation there can still be that turning back to the foundations of one’s life. I have trusted in you before, your love has not failed in the past, the how long will be not long and even though I may not see it now I can trust that I will indeed sing the songs of the LORD again.

1 Give ear, O heavens, and I will speak; let the earth hear the words of my mouth.

2 May my teaching drop like the rain, my speech condense like the dew;

like gentle rain on grass, like showers on new growth.

3 For I will proclaim the name of the LORD;

ascribe greatness to our God!

4 The Rock, his work is perfect, and all his ways are just.

A faithful God, without deceit, just and upright is he;

5 yet his degenerate children have dealt falsely with him,

a perverse and crooked generation.

6 Do you thus repay the LORD, O foolish and senseless people?

Is not he your father, who created you, who made you and established you?

7 Remember the days of old, consider the years long past;

ask your father, and he will inform you; your elders, and they will tell you.

8 When the Most High apportioned the nations, when he divided humankind,

he fixed the boundaries of the peoples according to the number of the gods;

9 the LORD’s own portion was his people, Jacob his allotted share.

10 He sustained him in a desert land, in a howling wilderness waste;

he shielded him, cared for him, guarded him as the apple of his eye.

11 As an eagle stirs up its nest, and hovers over its young;

as it spreads its wings, takes them up, and bears them aloft on its pinions,

12 the LORD alone guided him; no foreign god was with him.

13 He set him atop the heights of the land, and fed him with produce of the field;

he nursed him with honey from the crags, with oil from flinty rock;

14 curds from the herd, and milk from the flock, with fat of lambs and rams;

Bashan bulls and goats, together with the choicest wheat—

you drank fine wine from the blood of grapes.

This poem of Moses could fit in the book of Jeremiah as easily as the book of Deuteronomy. It in poetic form foreshadows the sweep of the Deuteronomic history which runs from Joshua to 1 and 2 Kings. This is a difficult song to write out and let the words seep out of the pen onto the paper as you hear them. It is dark, and as we heard in Deuteronomy 31:19 the purpose of the song is to be another witness against the people of Israel when they turn to be unfaithful. When they trust in other gods and the LORD abandons them (or actively brings about) the consequences the people are to know and understand. If the song looks forward, peering into the darkness of the future, the poet speaks the darkness in the hope that the words (for those are the only weapons the poet and songsmith have) might alter the path of the future. While the author of Deuteronomy has a dim view of the potential for the people of Israel to remain faithful, it is still their hope. Their anxiety over the disaster they foresee is matched by the intensity of the words they use to try to wake up the people to change the course they seem to be marching upon.

The song begins in praise of the God of Israel and the faithfulness of that God. Throughout this song the Rock will become the metaphorical name for God and be a contrast between the unbending faithfulness of the LORD the God of Israel and the degenerate children of a perverse and crooked generation. Yet, even this generation is called back to their ancestors who still remember and the elders who still trust in the LORD. Just as throughout the book of Deuteronomy it is the responsibility of the previous generation to ensure the fidelity of the upcoming generations, to remind them over and over of the way in which their God has provided for them and the special relationship they have with their God.

One of the reasons that many scholars think this is an early poem (or at a minimum this first section) is that it is not strictly monotheistic. The LORD allots to the other nations other gods, and what make Israel unique is that the Most High God has chosen them and therefore they are to have no other gods before the LORD their God. In beautiful poetic language it expresses that the people are God’s beloved and the ways in which God has sheltered and provided for them. God is an eagle hovering over its nest or bearing its young into the air on its wings. The LORD has provided all the best things: crops of the field, milk and curds from the cows and goats, the best meat from the sheep and bulls and goats, fine wine and bread. Yet, the fear of Deuteronomy is that in the midst of abundance that the people will forget who provided for them. That is where the poem takes its dark turning.

15 Jacob ate his fill; Jeshurun grew fat, and kicked. You grew fat, bloated, and gorged!

He abandoned God who made him, and scoffed at the Rock of his salvation.

16 They made him jealous with strange gods, with abhorrent things they provoked him.

17 They sacrificed to demons, not God, to deities they had never known,

to new ones recently arrived, whom your ancestors had not feared.

18 You were unmindful of the Rock that bore you; you forgot the God who gave you birth.

19 The LORD saw it, and was jealous he spurned his sons and daughters.

20 He said: I will hide my face from them, I will see what their end will be;

for they are a perverse generation, children in whom there is no faithfulness.

21 They made me jealous with what is no god, provoked me with their idols.

So I will make them jealous with what is no people, provoke them with a foolish nation.

22 For a fire is kindled by my anger, and burns to the depths of Sheol;

it devours the earth and its increase, and sets on fire the foundations of the mountains.

23 I will heap disasters upon them, spend my arrows against them:

24 wasting hunger, burning consumption, bitter pestilence.

The teeth of beasts I will send against them, with venom of things crawling in the dust.

25 In the street the sword shall bereave, and in the chambers terror,

for young man and woman alike, nursing child and old gray head.

As I’ve been listening to this song of Moses throughout this week I’ve also been reflecting upon the way other popular songs work to try to bring about change and yet may feel overwhelmed by the social forces that seem to be giving rise to the undesired reality. For example, when the punk band Green Day released their American Idiot CD they weren’t desiring the character of the American Idiot to be the reality, they were mocking the emerging culture controlled by a conservative media. Countless songs from numerous genres could be lifted up as attempting to be a voice calling upon the future to change and yet the poets may feel powerless as in the classic Simon and Garfunkel song, The Sound of Silence:

“Fools” said I, “you do not know

Silence like a cancer grows

Hear my words that I might teach you

Take my arms that I might reach you”

But my words like silent raindrops fell

And echoed in the wells of silence

Here the words of the song are placed in Moses’ mouth and just as in the previous chapter the hope is that the words will turn the direction that the people are moving in even when the anxiety is that the words will echo in the wells of silence. The words may bear witness but the people are hearing without listening. Moses prophetically chimes against when the people will bow and pray to the gods of stone and iron and gold they will make. In their fatness and wealth, they will forget the source of their blessings and attribute it to themselves and other things. Later prophets, like Jeremiah, who will attempt to be an echo of the words of this song will be treated as traitors, as woe bringers and will be resisted throughout their life. In the poetry of the song and of the later prophets sometimes the LORD will passively hide God’s face and surrender people to their fate, at other times God will actively bring upon the people their destruction, famine, and illness. In exchanging their Rock for idols of stone they have turned away from their foundation and reason for being. The song desperately rages to try to call the people to return to the LORD their God, and yet it knows people are likely to craft images of other gods rather than accept the God whom they cannot make an image of.

26 I thought to scatter them and blot out the memory of them from humankind;

27 but I feared provocation by the enemy, for their adversaries might misunderstand and say,

“Our hand is triumphant; it was not the LORD who did all this.”

28 They are a nation void of sense; there is no understanding in them.

29 If they were wise, they would understand this; they would discern what the end would be.

30 How could one have routed a thousand, and two put a myriad to flight,

unless their Rock had sold them, the LORD had given them up?

As in the book of Jeremiah, much of the language here is of a wounded God, a God who is contemplating the betrayal of the people of God. Woven into this song is the appeal of Moses in Exodus 32: 11-14 where he appeals to God on behalf of the people after the incident with the golden calf.

11 But Moses implored the LORD his God, and said, “O LORD, why does your wrath burn hot against your people, whom you brought out of the land of Egypt with great power and with a mighty hand? 12 Why should the Egyptians say, ‘It was with evil intent that he brought them out to kill them in the mountains, and to consume them from the face of the earth’? Turn from your fierce wrath; change your mind and do not bring disaster on your people. 13 Remember Abraham, Isaac, and Israel, your servants, how you swore to them by your own self, saying to them, ‘I will multiply your descendants like the stars of heaven, and all this land that I have promised I will give to your descendants, and they shall inherit it forever.'” 14 And the LORD changed his mind about the disaster that he planned to bring on his people.

Here the logic of Moses now becomes woven into the logic of God and the logic of the song. It is so other nations do not become puffed up in their own accomplishment that a remnant is allowed to remain. In a set of brokenhearted lyrics where the LORD no longer appears to love the people and yet feels obligated to save them yet again we find a reason for that remnant to remain.

31 Indeed their rock is not like our Rock; our enemies are fools.

32 Their vine comes from the vinestock of Sodom, from the vineyards of Gomorrah;

their grapes are grapes of poison, their clusters are bitter;

33 their wine is the poison of serpents, the cruel venom of asps.

34 Is not this laid up in store with me, sealed up in my treasuries?

35 Vengeance is mine, and recompense, for the time when their foot shall slip;

because the day of their calamity is at hand, their doom comes swiftly.

36 Indeed the LORD will vindicate his people, have compassion on his servants,

when he sees that their power is gone, neither bond nor free remaining.

37 Then he will say: Where are their gods, the rock in which they took refuge,

38 who ate the fat of their sacrifices, and drank the wine of their libations?

Let them rise up and help you, let them be your protection!

39 See now that I, even I, am he; there is no god besides me.

I kill and I make alive; I wound and I heal; and no one can deliver from my hand.

40 For I lift up my hand to heaven, and swear: As I live forever,

41 when I whet my flashing sword, and my hand takes hold on judgment;

I will take vengeance on my adversaries, and will repay those who hate me.

42 I will make my arrows drunk with blood, and my sword shall devour flesh—

with the blood of the slain and the captives, from the long-haired enemy.

43 Praise, O heavens, his people, worship him, all you gods!

For he will avenge the blood of his children, and take vengeance on his adversaries;

he will repay those who hate him, and cleanse the land for his people.

The song ends with a move towards hope, much like in Deuteronomy 30 where now the LORD will turn on behalf of the remnant of the people once they have undergone the judgment. In a poetic turning the vanquished people now mock their former conquerors in their weakness after the LORD’s vengeance. For the people of Israel, the LORD is the primary actor and the gods of the nations are unable to stand in the presence of the LORD. Much like Isaiah 44: 9-20 which mocks the idols of the nations or Jeremiah 50-51 which speaks of the destruction of Babylon, these words can speak for the hopeless people with the hope of the LORD’s actions on the idols and the nations. The poem closes with warrior imagery for God (flashing sword, arrows drunk with blood, etc.) where God’s vengeance is acted out in a bloody fashion. I have talked about the warrior imagery of God in other place, but here for the people of Israel it is a reminder that there is no Rock like their rock. Even in their apparent weakness their God is a mighty God.

44 Moses came and recited all the words of this song in the hearing of the people, he and Joshua son of Nun. 45 When Moses had finished reciting all these words to all Israel, 46 he said to them: “Take to heart all the words that I am giving in witness against you today; give them as a command to your children, so that they may diligently observe all the words of this law. 47 This is no trifling matter for you, but rather your very life; through it you may live long in the land that you are crossing over the Jordan to possess.” 48 On that very day the LORD addressed Moses as follows: 49 “Ascend this mountain of the Abarim, Mount Nebo, which is in the land of Moab, across from Jericho, and view the land of Canaan, which I am giving to the Israelites for a possession; 50 you shall die there on the mountain that you ascend and shall be gathered to your kin, as your brother Aaron died on Mount Hor and was gathered to his kin; 51 because both of you broke faith with me among the Israelites at the waters of Meribath-kadesh in the wilderness of Zin, by failing to maintain my holiness among the Israelites. 52 Although you may view the land from a distance, you shall not enter it– the land that I am giving to the Israelites.”

As the song ends we are reminded once again that we are approaching the end of Moses’ story. Here, in contrast to the earlier narrative of Deuteronomy where the LORD is angry with Moses because of the people (see Deuteronomy 1: 37, 3: 26, 4:21), now we are linked back to the narrative of Numbers 20: 10-12 as the reason for Moses’ upcoming death. The stage is set for the final chapter of Deuteronomy where Moses ascends the mountain never to return, yet Moses still has a final blessing to declare upon the people prior to the ending of his journey. One final benediction to come from the teacher, leader, mediator, judge and bringer of the law to sustain the people on their journey into the promised land.

Sometimes in the deep wounds of the world

Those places where the spirit is reduced to groans

Where words only have the power to inflame and incite

And the cry of lament is still unspeakable

Living in the shock of the brutality of reality

Seeing the pain that you cannot stop

Or reeling from the hole that resides in your soul

Where the limit of words are reached

And tears speak a language of their own.

Those places where logic fails and poetry perishes

Where death steals away life too soon

And violence destroys the beauty of the ages

Where trust is overcome in betrayal

The deep wounds of the world that cry out

In sobs that surpass the limit of words