2 Kings 15: 1-7 King Azariah (Uzziah) of Judah

1 In the twenty-seventh year of King Jeroboam of Israel, King Azariah son of Amaziah of Judah began to reign. 2 He was sixteen years old when he began to reign, and he reigned fifty-two years in Jerusalem. His mother’s name was Jecoliah of Jerusalem. 3 He did what was right in the sight of the Lord, just as his father Amaziah had done. 4 Nevertheless, the high places were not taken away; the people still sacrificed and made offerings on the high places. 5 The Lord struck the king so that he had a defiling skin disease to the day of his death and lived in a separate house. Jotham the king’s son was in charge of the palace, governing the people of the land. 6 Now the rest of the acts of Azariah and all that he did, are they not written in the Book of the Annals of the Kings of Judah? 7 Azariah slept with his ancestors; they buried him with his ancestors in the city of David; his son Jotham succeeded him.

King Azariah, also known as King Uzziah, has a long and successful reign over Judah. Uzziah and Azariah are used interchangeably in scriptures and even in this chapter and Uzziah was likely the name he assumed as king of Judah. His fifty-two-year reign begins in the middle of the forty-one year reign of Jeroboam II and both kings enjoy a period of military success and national resurgence. Azariah’s long and stable reign contrasts with his two predecessors (Joash and Amaziah) who saw the royal and temple treasuries diminished and in their political or military weakness were ultimately assassinated by those who served them. The stability during the time of Azariah in Judah also contrasts sharply with the instability in Samaria after the death of Jeroboam II.

Although 2 Kings does not spend a lot of time on the reign of Azariah/Uzziah his story is greatly expanded in 2 Chronicles 26. According to 2 Chronicles Azariah/Uzziah is a successful military leader who wins victories over Philistia, Ammon and extends Judah’s trade and military influence over the region. 2 Kings 14:22 gives a small window into the king’s success when it notes, “He rebuilt Elath and restored it to Judah after King Amaziah slept with his ancestors.” This small note indicates a large accomplishment only shared by Solomon, Jehoshaphat and Hezekiah. This gave Judah a port on the Mediterranean but also required them to control not only the port but the wilderness between. Alex Israel notes that he controls both major highways between Egypt and Mesopotamia, a lucrative trade route and source of income for the nation. (Israel, 2019, p. 227) 2 Chronicles also notes that King Uzziah strengthened the city walls of Jerusalem and increased the agricultural output of the land by his improvements and built up the army.

2 Kings’ brief account of this king who did what was right in the sight of the LORD ends with the jarring note that the LORD struck the king with ‘a defiling skin disease.’ This skin disease was traditionally rendered leprosy in most translations although we now believe that Hanson’s disease (which is what we call leprosy today) did not exist in the Middle East during this time. Yet, this affliction was normally associated with a judgment from God, and 2 Chronicles tells of the king entering the temple to offer incense, the job of the priests, and being struck with ‘leprosy’ as a punishment. Ultimately in 2 Chronicles the king is punished for overstepping his responsibility, attempting to fulfill both the kingly and the priestly role and ends his life separated from the palace and his responsibilities were assumed by his son Jotham until he died.

It is interesting that 2 Kings does not go into the success and fall of Azariah/Uzziah in the same manner as 2 Chronicles. Perhaps the narrator of 2 Kings doesn’t want to focus on the military success of Azariah in contrast to the lack of success by Joash and Amaziah who are both evaluated as kings who did what was right in the site of the LORD and at the same time does not want to focus on the act that leads to the king’s affliction. Despite the short narration of Azariah’s lengthy reign it is a consequential time as Judah remains stable as Northern Israel becomes chaotic and is one generation from collapse. This is also a time of prophetic voices and Isaiah (first Isaiah), Amos, Hosea, and Micah all give voice to this time in Israel and Judah.

2 Kings 15: 8-12 The Brief Reign of Zechariah King of Israel and the End of the Jehu Dynasty

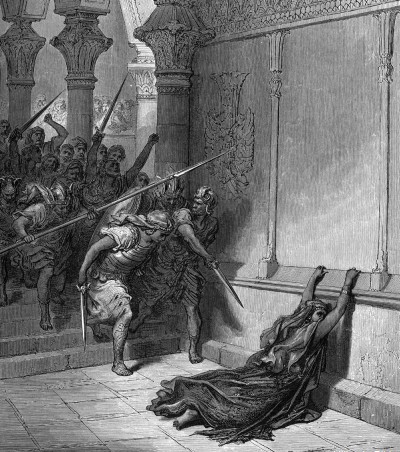

8 In the thirty-eighth year of King Azariah of Judah, Zechariah son of Jeroboam reigned over Israel in Samaria six months. 9 He did what was evil in the sight of the Lord, as his ancestors had done. He did not depart from the sins of Jeroboam son of Nebat that he caused Israel to sin. 10 Shallum son of Jabesh conspired against him and struck him down in Ibleam and killed him and reigned in place of him. 11 Now the rest of the deeds of Zechariah are written in the Book of the Annals of the Kings of Israel. 12 This was the promise of the Lord that he gave to Jehu, “Your sons shall sit on the throne of Israel to the fourth generation.” And so it happened.

The message of the LORD to Jehu after the destruction of the Omri dynasty indicated that his line would continue for four generations (2 Kings 10:30) and now after the death of Jeroboam II, the fourth generation, the Jehu dynasty collapses six months later. Jehu’s line ruled in Samaria for ninety-two years and it was enjoying a period of success under Jeroboam II, but the public murder of Zechariah ignites a power for struggle that will be violent and ultimately weaken Northern Israel as the Assyrian empire under Tiglath-Pileser III ascends. Zechariah is the first of a group of inconsequential kings in Samaria whose cumulative impact is very consequential in weakening Israel in a dangerous world.

2 Kings 15: 13-31 A Tumultuous Period in Israel

13 Shallum son of Jabesh began to reign in the thirty-ninth year of King Uzziah of Judah; he reigned one month in Samaria. 14 Then Menahem son of Gadi came up from Tirzah and came to Samaria; he struck down Shallum son of Jabesh in Samaria and killed him; he reigned in place of him. 15 Now the rest of the deeds of Shallum, including the conspiracy that he made, are written in the Book of the Annals of the Kings of Israel. 16 At that time Menahem sacked Tiphsah, all who were in it and its territory from Tirzah on; because they did not open it to him, he sacked it. He ripped open all the pregnant women in it.

17 In the thirty-ninth year of King Azariah of Judah, Menahem son of Gadi began to reign over Israel; he reigned ten years in Samaria. 18 He did what was evil in the sight of the Lord; he did not depart all his days from any of the sins of Jeroboam son of Nebat that he caused Israel to sin. 19 King Pul of Assyria came against the land; Menahem gave Pul a thousand talents of silver, so that he might help him confirm his hold on the royal power. 20 Menahem exacted the silver from Israel, that is, from all the wealthy, fifty shekels of silver from each one, to give to the king of Assyria. So the king of Assyria turned back and did not stay there in the land. 21 Now the rest of the deeds of Menahem and all that he did, are they not written in the Book of the Annals of the Kings of Israel? 22 Menahem slept with his ancestors, and his son Pekahiah succeeded him.

23 In the fiftieth year of King Azariah of Judah, Pekahiah son of Menahem began to reign over Israel in Samaria; he reigned two years. 24 He did what was evil in the sight of the Lord; he did not turn away from the sins of Jeroboam son of Nebat that he caused Israel to sin. 25 Pekah son of Remaliah, his captain, conspired against him with fifty of the Gileadites and attacked him in Samaria, in the citadel of the palace along with Argob and Arieh; he killed him and reigned in place of him. 26 Now the rest of the deeds of Pekahiah and all that he did are written in the Book of the Annals of the Kings of Israel.

27 In the fifty-second year of King Azariah of Judah, Pekah son of Remaliah began to reign over Israel in Samaria; he reigned twenty years. 28 He did what was evil in the sight of the Lord; he did not depart from the sins of Jeroboam son of Nebat that he caused Israel to sin.

29 In the days of King Pekah of Israel, King Tiglath-pileser of Assyria came and captured Ijon, Abel-beth-maacah, Janoah, Kedesh, Hazor, Gilead, and Galilee, all the land of Naphtali, and he carried the people captive to Assyria. 30 Then Hoshea son of Elah made a conspiracy against Pekah son of Remaliah, attacked him, and killed him; he reigned in place of him, in the twentieth year of Jotham son of Uzziah. 31 Now the rest of the acts of Pekah and all that he did are written in the Book of the Annals of the Kings of Israel.

Shallum son of Jabesh, Menahem son of Gadi, Pekahiah son of Menahem and Peka son of Remaliah all struggle for power during the stable reign of Azariah/Uzziah and (during Pekah’s reign in Samaria) the transition to Azariah’s son Jothan. Shallum reigns only for a month before he is overthrown by Menahem. Menahem assumes power in a violent manner and his description of sacking Tiphsah and tearing open the wombs of pregnant women describes him like the worst oppressors of Israel[1] and it is the violent ones who have ascended to power. Menahem may reign for ten years in Samaria but the large tribute payment[2] to Assyria under Tiglath-Pileser III[3] that he extracts from the gibbor hahayil (NRSVue ‘wealthy’)[4] likely means he is ruling with the political and even possibly military support of Assyria. When he dies his son is only to reign for two years. There are likely factions looking to align the nation with Assyria or Egypt as Hosea states:

Ephraim has become like a dove,

silly and without sense;

they call upon Egypt, they go to Assyria. (Hosea 7:11)

This is conjecture, but if Peka son of Remaliah ended the alliance with Assyria it would make sense of Tiglath-Pileser III seizing territory as well as dragging the captured people into exile. Records from Assyria indicate that there was a campaign against Israel in 733-732 BC and they took 13,520 people into exile. (Israel, 2019, p. 238) The Assyrian were known for taking exiles and displacing them to where they are totally dependent on Assyria and forced to blend into the larger Assyrian world. (Cogan, 1988, p. 177) The enemy has been within Samaria with this string of strongmen seizing power but now they face a much larger threat which is penetrating their borders and capturing the people and Israel appears powerless to resist.

2 Kings 15: 32-38 King Jothan of Judah

32 In the second year of King Pekah son of Remaliah of Israel, King Jotham son of Uzziah of Judah began to reign. 33 He was twenty-five years old when he began to reign, and he reigned sixteen years in Jerusalem. His mother’s name was Jerusha daughter of Zadok. 34 He did what was right in the sight of the Lord, just as his father Uzziah had done. 35 Nevertheless, the high places were not removed; the people still sacrificed and made offerings on the high places. He built the upper gate of the house of the Lord. 36 Now the rest of the acts of Jotham and all that he did, are they not written in the Book of the Annals of the Kings of Judah? 37 In those days the Lord began to send King Rezin of Aram and Pekah son of Remaliah against Judah. 38 Jotham slept with his ancestors and was buried with his ancestors in the city of David, his ancestor; his son Ahaz succeeded him.

In contrast to the bloody and dangerous instability of Samaria, Judah continues to function under another king of the Davidic line who does what is right in the sight of the LORD. 2 Chronicles 27 indicates that Jothan continues to build up the walls and defenses of Judah, and the king is likely aware of the growing threat to the north in Assyria. Again, 2 Chronicles portrays Jothan as a militarily successful king and in 2 Kings we have indication of both Aram and Samaria/Northern Israel attacking Judah (possibly as agents of Assyria) yet we do not have any indication that Judah is losing territory. Resin and Pekah may be attempting to raid for resources in their own struggles against the rising might of Assyria, but for the moment the threat to stable Judah is significantly less than it appears to be for Northern Israel.

[1] See for example Elisha’s description of what Hazael will do in 2 Kings 8:12, the accusations against Edom in Amos 1:13, or the judgement oracle of Hosea 13:16.

[2] Roughly seventy five thousand pounds of silver.

[3] King Pul is a nickname in late sources for Tiglath-Pileser III, and the use of this title in 2 Kings indicated the familiarity of the narrator with this leader of Assyria. (Israel, 2019, p. 238)

[4] Gibbor hahayil is often rendered mighty ones and often this was assumed to have military connotations. This term is common in the book of Judges, but it also can refer to landowners like Boaz in the book of Ruth. Wealthy may be the proper translation, but with Menahem being a warrior leader, it may also indicate something like warlords who are maintaining power beneath him.