Psalm 118

1 O give thanks to the LORD, for he is good; his steadfast love endures forever!

2 Let Israel say, “His steadfast love endures forever.”

3 Let the house of Aaron say, “His steadfast love endures forever.”

4 Let those who fear the LORD say, “His steadfast love endures forever.”

5 Out of my distress I called on the LORD; the LORD answered me and set me in a broad place.

6 With the LORD on my side I do not fear. What can mortals do to me?

7 The LORD is on my side to help me; I shall look in triumph on those who hate me.

8 It is better to take refuge in the LORD than to put confidence in mortals.

9 It is better to take refuge in the LORD than to put confidence in princes.

10 All nations surrounded me; in the name of the LORD I cut them off!

11 They surrounded me, surrounded me on every side; in the name of the LORD I cut them off!

12 They surrounded me like bees; they blazed like a fire of thorns; in the name of the LORD I cut them off!

13 I was pushed hard, so that I was falling, but the LORD helped me.

14 The LORD is my strength and my might; he has become my salvation.

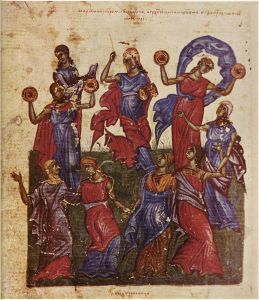

15 There are glad songs of victory in the tents of the righteous: “The right hand of the LORD does valiantly;

16 the right hand of the LORD is exalted; the right hand of the LORD does valiantly.”

17 I shall not die, but I shall live, and recount the deeds of the LORD.

18 The LORD has punished me severely, but he did not give me over to death.

19 Open to me the gates of righteousness, that I may enter through them and give thanks to the LORD.

20 This is the gate of the LORD; the righteous shall enter through it.

21 I thank you that you have answered me and have become my salvation.

22 The stone that the builders rejected has become the chief cornerstone.

23 This is the LORD’s doing; it is marvelous in our eyes.

24 This is the day that the LORD has made; let us rejoice and be glad in it.

25 Save us, we beseech you, O LORD! O LORD, we beseech you, give us success!

26 Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the LORD. We bless you from the house of the LORD.

27 The LORD is God, and he has given us light. Bind the festal procession with branches, up to the horns of the altar.

28 You are my God, and I will give thanks to you; you are my God, I will extol you.

29 O give thanks to the LORD, for he is good, for his steadfast love endures forever.

Psalm 118 has the flow of a moment of worship with a repetition which easily leads to a responsive feel between the primary speaker and the congregation gathered. This psalm closes the Egyptian hallel psalms used during the Passover meal in the Jewish tradition and is the psalm for both Palm Sunday and Easter in the lectionary for Christians. Although we cannot know how this psalm was used in the time after its composition it does echo in all four gospels as they tell of the entry of Jesus into Jerusalem before the crucifixion as well as numerous other echoes throughout the New Testament. Martin Luther, while he was hiding at Coburg Castle during the Diet of Augsburg inscribed the words of verse seventeen on the wall as a message of confidence and reassurance. (Nancy deClaisse-Walford, 2014, p. 868) This worship like song of praise has shaped the practice and faith of countless generations of both Jewish and Christian faithful.

The opening words of Psalm 118 are words frequently used in gathering people for worship or concluding a prayer in worship in the Hebrew Scriptures. Chronicles uses nearly identical wording to close for David’s first psalm of thanksgiving when the ark of the covenant is brought into the tent of God, Solomon uses it while dedicating the temple, and Jehoshaphat uses these words in his reformation.[1] Both Psalm 106 and 107 have the same words in their opening verse. Particularly with the opening of Psalm 107 which begins book five of the psalter and Psalm 118 beginning and ending with this statement about the goodness of the LORD and the hesed (steadfast love NRSV) of God enduring forever may form both a bookend for the psalm but also for this portion of the psalter. Psalm 118 on its own and this group of psalms (107-118) can be grouped together as a reflection on the goodness and the hesed of God.

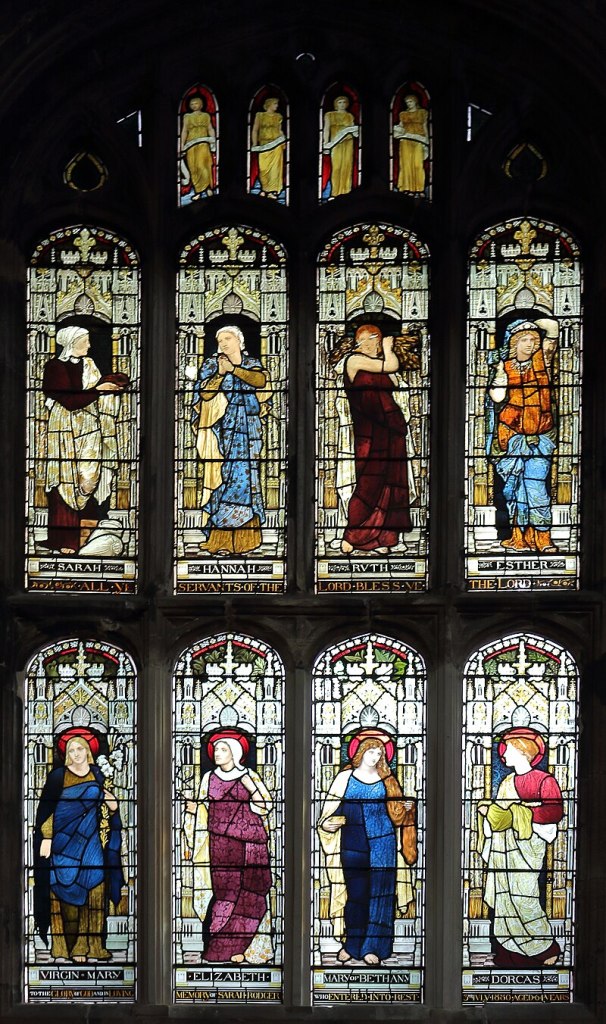

Israel, the house of Aaron, and those who fear the LORD are all to declare that the LORD’s hesed endures forever. These are the same trio of groups called upon to trust the LORD in Psalm 115: 9-11 and to the initial readers it was likely an emphatic way of referring to all of Israel, although most modern readers hear the final verse as expanding this trust and proclamation beyond Israel to ‘those who fear the LORD’ throughout the nations. For Psalm 118 the focus in the first four and final verse on the hesed of the LORD prepares the hearer of the psalm to reflect on the verses in between as demonstrating and explaining the unending hesed of the LORD.

The speaker speaks of the LORD’s rescue of them from a tight space. The Hebrew word for distress (mesar) in verse five has the sense of “narrow,” “restricted,” or “tight.” (NIB IV:1154) Knowing this fuller meaning gives a more poetic flow to the verse as the speaker is taken from a tight or narrow space into a broad place. This rescue leads the psalmist to speak in trust in confidence in the LORD’s ability to deliver from anything that mortals and rulers (princes) may array against them. As the apostle Paul will later state to the church in Rome in an echo of this psalm, “If God is for us, who is against us.” (Romans 8:31b) The psalm echoes the common image of God as a refuge against these mortals and princes arrayed against them.

These enemies poetically swarm like bees, blaze like fire among thorns and push hard against the psalmist but the LORD cuts them off and helps the faithful one in distress. The words of verse fourteen through sixteen pulls on the words of the song of Moses in Exodus 15:1-18, ancient songs of faith whose words that become relevant to the psalmist’s experience of delivery. After the ordeal which pushed the psalmist hard but the LORD delivered, they can exclaim that “I shall not die, but I shall live, and recount the deeds of the LORD.”

Throughout the Hebrew scriptures there is a primary testimony that punishment and testing all come from God. Yet, even in that testing and punishment there is mercy where God does not abandon the psalmist and allows them to both endure the moment and enter into this time of praise and triumph. There is the movement through the gates of the righteous into the worship space where the psalmist can lift up his triumphal praise with the congregation of the faithful. Verse twenty-two which speaks of the stone the builders rejected probably referred to the psalmist originally (Nancy deClaisse-Walford, 2014, p. 868) but this psalm is used multiple times in the New Testament as a way of reflecting on the rejection and exaltation of Jesus.[2] This marvelous deliverance from the tight space to the broad place allows the psalmist and those gathered with him to realize that “this is a day that the LORD has made; let us rejoice and be glad in it.”

The psalm closes with what continues to feel like a triumphal procession which continues to seek the favor of the LORD as they celebrate the moment of triumph. As mentioned above, verse twenty-six echoes in the gospel narration of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem before his crucifixion. Even if we may not fully grasp the specifics of the worship event in the psalm where the festal procession is bound with branches, the movement towards the altar and the temple is clear. The people and the psalmist process in thanksgiving and praise to celebrate the experience of deliverance because of the hesed of God. They continue to worship the God they experience as a good God of unending steadfast love (hesed).

[1] 1 Chronicles 16:34; 2 Chronicles 5:13; 7:2; 20:21.

[2] Mark 12: 10-11; Acts 4: 11; Ephesians 2: 20-21; 1 Peter 2: 4-8.