Psalm 113

1 Praise the LORD! Praise, O servants of the LORD; praise the name of the LORD.

2 Blessed be the name of the LORD from this time on and forevermore.

3 From the rising of the sun to its setting, the name of the LORD is to be praised.

4 The LORD is high above all nations and his glory above the heavens.

5 Who is like the LORD our God, who is seated on high,

6 who looks far down on the heavens and the earth?

7 He raises the poor from the dust and lifts the needy from the ash heap,

8 to make them sit with princes, with the princes of his people.

9 He gives the barren woman a home, making her the joyous mother of children. Praise the LORD!

The God of the songs and stories of Israel is a God who turns the world upside down. The LORD of Israel is the one who is high above all nations and lords yet this God raises up the “triad of the wretched” (Bellinger, 2014, p. 490) the poor, the needy, and the barren. This is the LORD on high who lifts up the lowly. Psalm 113 echoes this paradoxical reality in Hebrew thought: the LORD is high above all things, and the LORD looks down and sees the lowliest of all things.

Psalm 113 begins and ends with Hallelujah (NRSV Praise the LORD!). Unlike the previous two psalms it is not an acrostic, instead it is a short poem with two easily discerned parts. In the first four verses the praising and honoring of the LORD is the focus. Verse five forms pivot where the psalmist asks, “Who is like the LORD our God, who is seated on high.” The final four verses consider how this LORD who is seated on high cares for the lowly.

The praise of the LORD in the first four verses continually mentions the LORD and the name of the LORD as the focus of the praise of the servants of the LORD. The name of the LORD, enshrined in the commandment to “not make wrongful use the name of the LORD your God,” (Exodus 20:7, Deuteronomy 5:11) is critical to the proper reverence of the God of Israel. Names in the ancient world were powerful things and this God whose name is to be praised at all times (from this time on forevermore and from the rising of the sun to its setting) was due the reverence afforded to the name of the LORD.[1] This God who is above all things and whose name is worthy of reverence is seated on high.

The LORD on high lifting up the lowly is easily seen in the English translations, but when the Hebrew is rendered in a more literal translation[2] the parallel is even clearer as J. Clinton McCann Jr. shows:

A more literal translation captures the effect; God “makes God’s self high in order to sit,” (v.5b) “makes God’s self low in order to see,” (v. 6a) “causes the poor to arise” (v.7a), “makes exalted the needy…to cause them to sit with princes.” (NIB IV: 1139)

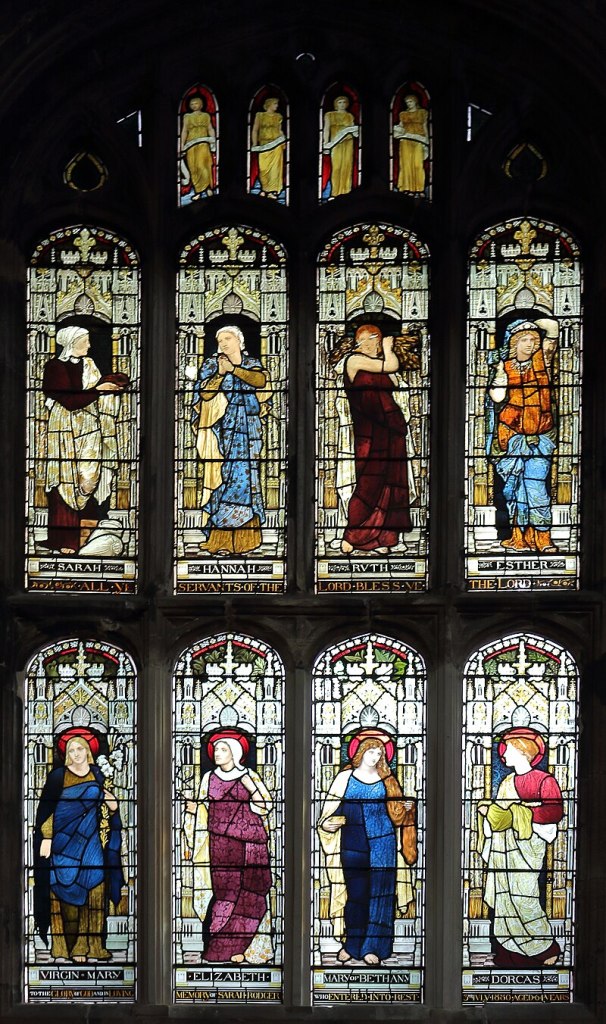

God intervenes in the life of the poor, the needy and the barren woman. God uses God’s position and power to lift up the lowly. This is the God of Sarah. Rebekah, and Rachel in the book of Genesis, these formerly barren women who became the joyous mothers of children. This is the God of the exodus who took a poor and needy people out of their captivity through the wilderness into the promised land. This is the God who hears the song of Hannah (1 Samuel 2) and Mary (Luke 1:46-55) which both share common themes with the second half of Psalm 113.

Psalm 113 in modern Jewish life is the first of the “Egyptian Hallel” psalms which are utilized in the Passover celebration. It is possible that this was the psalm that Jesus and his followers sang before they went out to the Mount of Olives after the Last Supper (Mark 14:26). The Psalm resonates strongly with many of the themes of the ministry of Jesus, just as it resonates with the story, songs, and the law. As Deuteronomy reminds the people:

For the LORD your God is God of gods and Lord of lords, the great God, mighty and awesome, who is not partial and takes no bribes, who executes justice for the orphan and the widow, and who loves the strangers, providing them with food and clothing. (Deuteronomy 10: 17-18)

This short psalm captures a central theme of the Hebrew and Christian scriptures: the paradox that the God who is high over all things sees and lifts up the lowly.

[1] The four letters of the divine name given to Moses in Exodus 3:14 are behind the English translation of LORD in all capitol letters. The practice of translating this LORD comes from the practice of using the vowel pointings for ‘Adonai” (Hebrew lord) on the consonants in Hebrew so that the reader knows not to utter the name of the LORD the God of Israel.

[2] Translators have to make a difficult choice when rendering a language into another of how to balance the literal meaning of the words with the different syntax and expectations of the language they are translating into. A “wooden” or “literal” translation is often difficult to read or understand because Hebrew sentences often do not include elements that most English readers are used to.