Grigory Mekheev, Exodus (2000) artist shared work under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

Psalm 78

<A Maskil of Asaph.>

1 Give ear, O my people, to my teaching; incline your ears to the words of my mouth.

2 I will open my mouth in a parable; I will utter dark sayings from of old,

3 things that we have heard and known, that our ancestors have told us.

4 We will not hide them from their children; we will tell to the coming generation the glorious deeds of the LORD, and his might, and the wonders that he has done.

5 He established a decree in Jacob, and appointed a law in Israel, which he commanded our ancestors to teach to their children;

6 that the next generation might know them, the children yet unborn, and rise up and tell them to their children,

7 so that they should set their hope in God, and not forget the works of God, but keep his commandments;

8 and that they should not be like their ancestors, a stubborn and rebellious generation, a generation whose heart was not steadfast, whose spirit was not faithful to God.

9 The Ephraimites, armed with the bow, turned back on the day of battle.

10 They did not keep God’s covenant, but refused to walk according to his law.

11 They forgot what he had done, and the miracles that he had shown them.

12 In the sight of their ancestors he worked marvels in the land of Egypt, in the fields of Zoan.

13 He divided the sea and let them pass through it, and made the waters stand like a heap.

14 In the daytime he led them with a cloud, and all night long with a fiery light.

15 He split rocks open in the wilderness, and gave them drink abundantly as from the deep.

16 He made streams come out of the rock, and caused waters to flow down like rivers.

17 Yet they sinned still more against him, rebelling against the Most High in the desert.

18 They tested God in their heart by demanding the food they craved.

19 They spoke against God, saying, “Can God spread a table in the wilderness?

20 Even though he struck the rock so that water gushed out and torrents overflowed, can he also give bread, or provide meat for his people?”

21 Therefore, when the LORD heard, he was full of rage; a fire was kindled against Jacob, his anger mounted against Israel,

22 because they had no faith in God, and did not trust his saving power.

23 Yet he commanded the skies above, and opened the doors of heaven;

24 he rained down on them manna to eat, and gave them the grain of heaven.

25 Mortals ate of the bread of angels; he sent them food in abundance.

26 He caused the east wind to blow in the heavens, and by his power he led out the south wind;

27 he rained flesh upon them like dust, winged birds like the sand of the seas;

28 he let them fall within their camp, all around their dwellings.

29 And they ate and were well filled, for he gave them what they craved.

30 But before they had satisfied their craving, while the food was still in their mouths,

31 the anger of God rose against them and he killed the strongest of them, and laid low the flower of Israel.

32 In spite of all this they still sinned; they did not believe in his wonders.

33 So he made their days vanish like a breath, and their years in terror.

34 When he killed them, they sought for him; they repented and sought God earnestly.

35 They remembered that God was their rock, the Most High God their redeemer.

36 But they flattered him with their mouths; they lied to him with their tongues.

37 Their heart was not steadfast toward him; they were not true to his covenant.

38 Yet he, being compassionate, forgave their iniquity, and did not destroy them; often he restrained his anger, and did not stir up all his wrath.

39 He remembered that they were but flesh, a wind that passes and does not come again.

40 How often they rebelled against him in the wilderness and grieved him in the desert!

41 They tested God again and again, and provoked the Holy One of Israel.

42 They did not keep in mind his power, or the day when he redeemed them from the foe;

43 when he displayed his signs in Egypt, and his miracles in the fields of Zoan.

44 He turned their rivers to blood, so that they could not drink of their streams.

45 He sent among them swarms of flies, which devoured them, and frogs, which destroyed them.

46 He gave their crops to the caterpillar, and the fruit of their labor to the locust.

47 He destroyed their vines with hail, and their sycamores with frost.

48 He gave over their cattle to the hail, and their flocks to thunderbolts.

49 He let loose on them his fierce anger, wrath, indignation, and distress, a company of destroying angels.

50 He made a path for his anger; he did not spare them from death, but gave their lives over to the plague.

51 He struck all the firstborn in Egypt, the first issue of their strength in the tents of Ham.

52 Then he led out his people like sheep, and guided them in the wilderness like a flock.

53 He led them in safety, so that they were not afraid; but the sea overwhelmed their enemies.

54 And he brought them to his holy hill, to the mountain that his right hand had won.

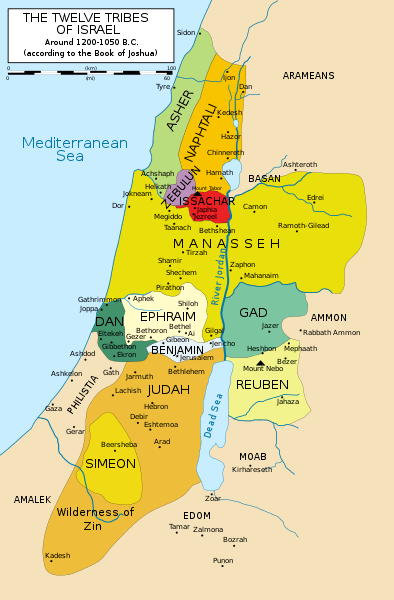

55 He drove out nations before them; he apportioned them for a possession and settled the tribes of Israel in their tents.

56 Yet they tested the Most High God, and rebelled against him. They did not observe his decrees,

57 but turned away and were faithless like their ancestors; they twisted like a treacherous bow.

58 For they provoked him to anger with their high places; they moved him to jealousy with their idols.

59 When God heard, he was full of wrath, and he utterly rejected Israel.

60 He abandoned his dwelling at Shiloh, the tent where he dwelt among mortals,

61 and delivered his power to captivity, his glory to the hand of the foe.

62 He gave his people to the sword, and vented his wrath on his heritage.

63 Fire devoured their young men, and their girls had no marriage song.

64 Their priests fell by the sword, and their widows made no lamentation.

65 Then the Lord awoke as from sleep, like a warrior shouting because of wine.

66 He put his adversaries to rout; he put them to everlasting disgrace.

67 He rejected the tent of Joseph, he did not choose the tribe of Ephraim;

68 but he chose the tribe of Judah, Mount Zion, which he loves.

69 He built his sanctuary like the high heavens, like the earth, which he has founded forever.

70 He chose his servant David, and took him from the sheepfolds;

71 from tending the nursing ewes he brought him to be the shepherd of his people Jacob, of Israel, his inheritance.

72 With upright heart he tended them, and guided them with skillful hand.

We narrate the story of our past to attempt to understand our present reality, and yet our narrations of the past are always shaped by our present experiences and questions. Psalm seventy-eight is a long narration of the rebellion of the people in the wilderness and God’s judgment of Egypt to force the release of the people of Israel. Yet, the narration is told not merely to relay historical information but to point to the impact of Israel’s failure to keep the covenant (Nancy deClaisse-Walford, 2014, p. 623) Within this historical retelling it focuses on God’s wrath as it is shown towards Israel even after God’s gracious action to deliver them from slavery and to provide food and water in the wilderness. God’s exercise of power for deliverance and provision does not seem to compel the people to obedience and it is only God’s wrath appears that the people change their ways and sought God’s ways. Martin Luther referred to God’s wrath as God’s alien work which reflects the belief that God is fundamentally gracious, but that disobedience provokes this alien expression of punishment or wrath from God. Living much of my life in Texas or the southeastern United States I have always wondered why so many people were drawn to churches that focused on God’s judgment and wrath which articulated clear but rigid definitions of insiders and outsiders having been raised and formed in a tradition that focused heavily on the grace of God, but perhaps for some the God of judgment is more comforting and the rigid boundaries are comfortable. Yet, the God presented by the Bible is both gracious and demanding. God hears the cries of the people and is roused to deliver them, but this same God who is the mighty warrior who delivers refuses to be taken for granted. The narration of the central story of the people of Israel, perhaps in a time where a portion of that people has fallen away, with an emphasis on obedience is to bring about fidelity to God and God’s covenant.

There is no scholarly consensus on the historical background of this psalm, but my suspicion is that it is probably written sometime after the fall of the northern kingdom in 722 BCE but prior to the Babylonian exile in 586 BCE. There are several pointed phrases about Ephraim, Shiloh, and Israel which indicate a perspective of the kingdom of Judah and there is an indication of a disaster in the northern kingdom which seems to be one more example of God’s judgment upon the unfaithful ones in the view of the psalmist.[1] Narrating the ancient and perhaps recent past to learn from it is one of the reasons for revisiting the memories of the people. We live in a world where the written scriptures are readily available, but in a world where the written word is painstakingly handed on and typically only available to priests or royalty this psalm may have been an important way of impressing the historical memory on the current and future generations.

The memory of the past is recited to the community to help it learn how to properly relate to its God. As Walter Brueggemann and William Bellinger can memorably state, “In the recital of memory there is hope for the future.” (Brueggemann, 2014, p. 340) The initial eleven verses are a call to listen and sets the expectations for the hearers to, “not be like their ancestors, a stubborn and rebellious generation…they did not keep the covenant, and they refused to walk according to his teaching:” (8,10) Ephraim, synonymous with the northern kingdom of Israel, is highlighted as being turned back in battle and as mentioned above this may suggest a situation after the conquest of Israel by the Assyrians. Recent events may set the backdrop for the hearing of this examination of the disobedience of the people during the Exodus.

There are two major narrations of the past in this psalm. Both share a common pattern of narrating God’s gracious act, a rebellion by the people, God’s response in anger to the disobedience of the people and a summary of the section. (Nancy deClaisse-Walford, 2014, p. 623) In the first section verses twelve through sixteen narrate God’s action to deliver the people from Egypt, pass them through the sea, lead them in the wilderness, and provide water in the wilderness. Yet, the response of the people in verses seventeen through twenty is to speak against God and to question God’s provision. Their lack of trust or gratitude provokes God and many of the strongest of the people die in this time. Yet, when God responds in judgment they seek him but even this seeking is halfhearted. Their words are deceitful, and their actions do not hold fast to the covenant God placed before them. Yet, God’s compassion restrains God’s wrath even though their actions cause God grief.

The second narration begins in verse forty-three looking back to God’s actions to bring the people out of Egypt. This second narration looks in amazement at all the actions God did in comparison to the continual rebellion of the people. There are some differences between the narration in Exodus 7-11 and the remembrance here, but it is clear they are pointing to a common memory. Yet, in the psalm time begins to compress as the hearers are moved from God’s action to deliver the people from Egypt, lead them through the wilderness and into the promised land seems to move to a more recent judgment beginning in verse fifty-six. The central focus of the judgment seems to be on the northern kingdom of Israel which is rejected with its holy place at Shiloh abandoned by God. God’s arousal from sleep liberates Judah, but Ephraim (northern Israel) is rejected. The psalm ends with Judah being delivered by God and cared for by David (and the Davidic line). Yet, just like Ephraim and the northern kingdom, Judah’s position is due to the gracious provision of God but carries the expectation to live within the covenant. The psalmist encourages the people to choose the way of faithfulness instead of the disobedient and stubborn ways of their ancestors and their brothers in the north.

The bible narrates a theological interpretation of history which focuses on the interaction between God and the people of God. Interpreters of scripture in both Jewish and Christian traditions have seen within the scriptures a witness to a tension within a God who desires to be gracious but whose people only seem to respond to punishment or wrath. In Beth Tanner’s words this psalm,

tells of God’s great passion for humans, even when those humans turn away. It also tells the sad story of human determination to ignore the good gifts of God and to remember God only when the way becomes hard or violent. (Nancy deClaisse-Walford, 2014, p. 625)

God’s anger and wrath may be, to use Luther’s term, God’s alien work but the God of scripture refuses to be taken for granted. God is jealous for the people’s attention and allegiance and when the people turn away from God’s gifts God responds. I tell my congregation that “God wants to meet you in grace and love and peace, but if you can only hear God in judgment God will meet you there even though it creates a struggle within God.” We still come together and remember these stories to learn from the wisdom and the struggles of our ancestors in faith, to seek God in grace, to live in obedience and faithfulness but also to attempt to interpret our world in light of God’s gifts and God’s discipline. This may be harder in our very secular world but just as we attempt to learn from our more recent history, we listen to the narration of the psalmist to the memory of the people and learn from their life with God under grace and under judgment.

[1] See for example verses 9, 56-64, and 67