2 Kings 3

1 In the eighteenth year of King Jehoshaphat of Judah, Jehoram son of Ahab became king over Israel in Samaria; he reigned twelve years. 2 He did what was evil in the sight of the Lord, though not like his father and mother, for he removed the pillar of Baal that his father had made. 3 Nevertheless, he clung to the sin of Jeroboam son of Nebat that he caused Israel to commit; he did not depart from it.

4 Now King Mesha of Moab was a sheep breeder who used to deliver to the king of Israel one hundred thousand lambs and the wool of one hundred thousand rams. 5 But when Ahab died, the king of Moab rebelled against the king of Israel. 6 So King Jehoram marched out of Samaria at that time and mustered all Israel. 7 As he went he sent word to King Jehoshaphat of Judah, “The king of Moab has rebelled against me; will you go with me to battle against Moab?” He answered, “I will; I am as you are; my people are your people; my horses are your horses.” 8 Then he asked, “By which way shall we march?” Jehoram answered, “By the way of the wilderness of Edom.”

9 So the king of Israel, the king of Judah, and the king of Edom set out, and when they had made a roundabout march of seven days, there was no water for the army or for the animals that were with them. 10 Then the king of Israel said, “Alas! The Lord has summoned these three kings to hand them over to Moab.” 11 But Jehoshaphat said, “Is there no prophet of the Lord here through whom we may inquire of the Lord?” Then one of the servants of the king of Israel answered, “Elisha son of Shaphat, who used to pour water on the hands of Elijah, is here.” 12 Jehoshaphat said, “The word of the Lord is with him.” So the king of Israel and Jehoshaphat and the king of Edom went down to him.

13 Elisha said to the king of Israel, “What have I to do with you? Go to your father’s prophets or to your mother’s.” But the king of Israel said to him, “No; it is the Lord who has summoned these three kings to hand them over to Moab.” 14 Elisha said, “As the Lord of hosts lives, whom I serve, were it not that I have regard for King Jehoshaphat of Judah, I would give you neither a look nor a glance. 15 But get me a musician.” And then, while the musician was playing, the hand of the Lord came on him. 16 And he said, “Thus says the Lord: I will make this wadi full of pools. 17 For thus says the Lord: You shall see neither wind nor rain, but the wadi shall be filled with water, so that you shall drink, you, your army, and your animals. 18 This is only a trifle in the sight of the Lord, for he will also hand Moab over to you. 19 You shall conquer every fortified city and every choice city; every good tree you shall fell, all springs of water you shall stop up, and every good piece of land you shall ruin with stones.” 20 The next day, about the time of the morning offering, suddenly water began to flow from the direction of Edom until the country was filled with water.

21 When all the Moabites heard that the kings had come up to fight against them, all who were able to put on armor, from the youngest to the oldest, were called out and were drawn up at the frontier. 22 When they rose early in the morning and the sun shone upon the water, the Moabites saw the water opposite them as red as blood. 23 They said, “This is blood; the kings must have fought together and killed one another. Now then, Moab, to the spoil!” 24 But when they came to the camp of Israel, the Israelites rose up and attacked the Moabites, who fled before them; as they entered Moab, they continued the attack. 25 The cities they overturned, and on every good piece of land everyone threw a stone until it was covered; every spring of water they stopped up, and every good tree they felled. Only at Kir-hareseth did the stone walls remain until the slingers surrounded and attacked it. 26 When the king of Moab saw that the battle was going against him, he took with him seven hundred swordsmen to break through opposite the king of Edom, but they could not. 27 Then he took his firstborn son who was to succeed him and offered him as a burnt offering on the wall. And great wrath came upon Israel, so they withdrew from him and returned to their own land.

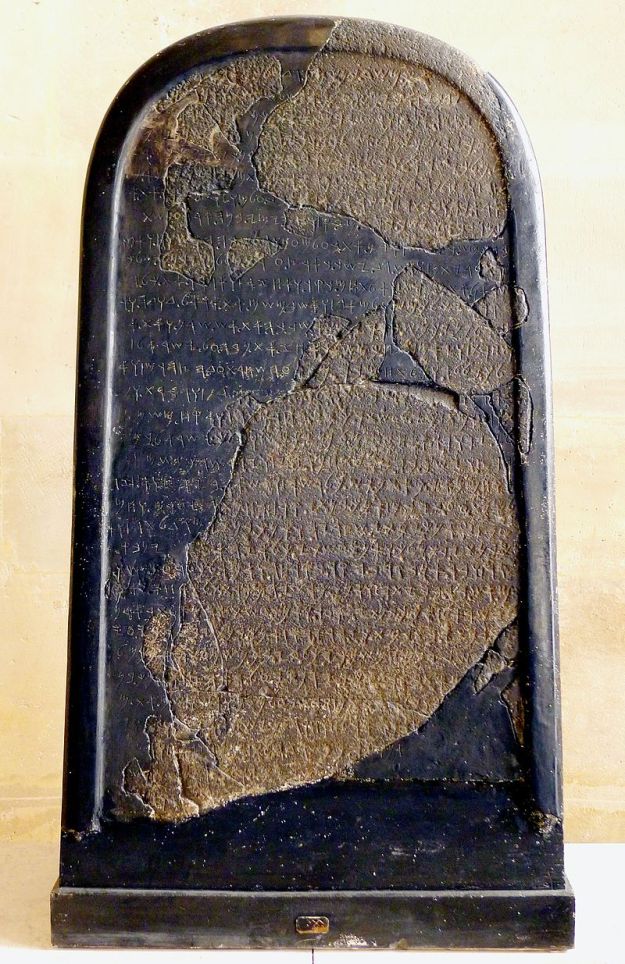

This is a strange story for several reasons. On the one hand it is a story of a bad, but not as bad as his predecessors, king of Israel who calls on an alliance with the kings of Judah and Edom. The king of Israel is not portrayed in a favorable light and Elisha has no regard for him. The act of prophesy by Elisha is also linked to a performance of a musician which sets the mood for a prophetic state. The prophetic command is also strange since it contradicts the rules for war outlined in Deuteronomy. Finally, the strangest note is at the end when the king of Moab’s sacrifice of his firstborn son turns the tide and Israel withdraws. Yet, this is also an interesting passage for historians who have the ‘Mesha Stele’ which provides an independent witness to this time-period from the perspective of Moab.

From a historical perspective the discovery of the ‘Mesha Stele’ confirms several points of the 2 Kings narrative. King Mesha of Moab was ‘oppressed’ by the Omri dynasty, likely paying tribute to the king. In the view of King Mesha this situation is due to Chemosh, the god of the Moabites, being displeased with his people. Finally, it confirms an uprising of Mesha against a son of Omri, presumably Jehoram, in which King Mesha accomplishes some victories. The precipitating events which cause the king of Israel to reach out to his allies and begin to take military action against Moab are given an independent witness by this discovery. This also makes sense within the previous narrative where King Ahab dies and Moab rebels in 2 Kings 1:1. Ahaziah’s brief reign, cut short by his fall and then sending messengers to Ekron seeking insight from Baal-zebub, made him too weak of a leader to respond to this rebellion.

There are numerous similarities between this narrative and the conflict between Aram and the Israel and Judah mentioned in 1 Kings 22. In both narratives King Jehoshaphat of Judah replies both as and ally, but also the weaker party in the relationship, willingly committing his forces to the king of Israel’s conflict. In both stories it is the king of Judah who requests that they seek out the opinion of a prophet of the LORD that is not tied to the royal apparatus of the king of Israel. Unlike the previous story the outcome is mostly favorable for both the king of Israel and the king of Judah.

King Mesha is noted as a sheep-breeder, and his tribute is an excessive quantity of both lambs and wool. There is no time-period for the tribute so it may be an annual tribute, or it may be the tribute over the time of subservience. Although King Mesha may simply preside, “over a semi-nomadic economy in Moab. The principle industry is sheep and the principle products are wool and lamb.” (Brueggemann, 2000, p. 306) It is also worth noting that throughout scripture kings are often portrayed metaphorically as shepherds. The king may be directly involved in sheep-breeding, but it is equally likely that he is the ‘shepherd’ of a people whose primary livelihood revolves around sheep.

The king of Israel moves his army through Judah and through Edom to attack Moab from the south. This move is likely to approach Moab from a direction they do not expect and to utilize the element of surprise, but any advantage quickly dissipates when the army runs out of water. It is possible that springs or waters they expected to utilize had dried up or that they simply failed to adequately plan and scout the route, but the situation results in an army foundering in the wilderness and vulnerable to the king of Moab’s attack. Jehoram interprets this as a sign of the LORD’s displeasure, but Jehoshaphat suggests they inquire of a prophet of the LORD. Apparently, Elisha has either been traveling in proximity of the company or has at some earlier point moved to the wilderness of Edom to be available at this moment of the kings’ peril.

According to the evaluation of 2 Kings, Jehoram is still a bad king but not as bad as his predecessors. Sometime in his reign he is reported to have removed the pillar of Baal (likely after the LORD’s deliverance in this narrative) and according to the narrative of 2 Kings, he believes that the LORD the God of Israel has called the three kings together in this mission and is also punishing them. Even though it is King Jehoshaphat of Judah who asks to consult a prophet of the LORD, King Jehoram does not seem to resist the kings going to consult with Elisha nor does he push back against Elisha’s harsh words. Elisha, like his predecessor Elijah, has little use for the kings of the Omri dynasty but he does respect the king of Judah.

Elisha requests a musician and then has a moment when the hand of the LORD comes upon him. The hand of the LORD coming upon Elisha was likely viewed by the observers as an ecstatic experience and there is an expectation of prophets being overtaken by an experience they cannot control.[1] Elisha’s message brings an answer not only to the immediate problem of water, but it also foretells victory over their Moabite opponents. Yet, strangely, the prophet’s commands violate the expectations of conflict outlined in Deuteronomy which prohibits the chopping down of trees.[2] There is a biblical desire to preserve the land. In ancient warfare it is common attempt to deny your enemy the fruitfulness of the land, which is what the prophet’s guidance indicates, but the tension between the law in Deuteronomy and the prophet’s guidance is one additional strange element to this strange story.

The Hebrew storytellers love wordplay and allusion to other narratives, and in the Moabites response to these kings in the wilderness. The waters being red as blood recalls on of God’s first major actions to bring the people out of Egypt by turning the waters of the Nile to blood.[3] But the scene also plays on the origin story of Edom in Genesis being Esau, Jacob/Israel’s brother, whose name means ‘red’ and is famous for selling his birthright for ‘red stuff.’[4] We don’t know why the Moabites interpret the red looking water as blood, but it causes them to camp of Israel in a less cautious manner.

The overall progression of the battle is portrayed as a rout where Israel and its allies overwhelm the Moabite advance on their camp and then proceed to follow Elisha’s guidance against the land and the cities. Only Kir-hareseth’s[5] stone wall briefly stops the advance before slingers attack it. The victories of Israel are not strange in this narrative, but the halting of the success is.

The final verse of this chapter has provoked the greatest debate among interpreters as they wrestle with how to deal with the implications of wrath coming upon Israel as a result of the King of Moab’s sacrifice. The bible shares with the rest of the ancient world the belief that there is power in blood and there is in many ancient belief systems an idea that appears in many fantasy worlds that connects blood, particularly the shedding of blood, in the practice of magic or appeasing deities or demons. The most literal interpretation of the words is that King Mesha sacrifices his first-born heir to Chemosh on the wall and this awakens Chemosh who grants the Moabites power against their foes. The Hebrew scriptures are insistent that the LORD is above all other gods, but it also assumes a world where these other gods of the nations do have power. The offense of this interpretation is that Chemosh successfully resists the LORD and halts the prophesied conquest over Moab. Rabbinic exegetes give an explanation that the son sacrificed is the son of the king of Edom, the ally of Israel and Judah, and this sacrifice causes Edom to turn against his allies. (Cogan, 1988, p. 48) Brueggemann speaks for a lot of modern readers when he states, “The most remarkable fact about the narrative is that everything we would most like to know is left unsaid.” (Brueggemann, 2000, p. 315) It is a strange ending to a strange story. It is unusual that a story where another god may have prevented the outcome the LORD’s prophet indicated to be completed. Yet, the story does not give any reason for the King Mesha of Moab being able to finally resist the kings of Israel, Judah and Edom as well as the LORD who stands behind them.

[1] 1 Samuel 10: 9-13; 19: 23-24.

[4] Genesis 25: 25, 30.

[5] Brueggemann notes on Kir-hareseth, “Nothing is known of this city, the site of Israel’s last success in this military campaign. However, the mention of the city in Isa 16;7, Jer 48:31, 36 as a poetic parallel for “Moab” suggest that it was a major site, certainly a freighted item in the prophet’s imagination. (Brueggemann, 2000, p. 313)