“Othniel” by the French Painter James Tissot (1836-1902)

Judges 3:1-6 The Remaining Nations

Now these are the nations that the LORD left to test all those in Israel who had no experience of any war in Canaan 2 (it was only that successive generations of Israelites might know war, to teach those who had no experience of it before): 3 the five lords of the Philistines, and all the Canaanites, and the Sidonians, and the Hivites who lived on Mount Lebanon, from Mount Baal-hermon as far as Lebo-hamath. 4 They were for the testing of Israel, to know whether Israel would obey the commandments of the LORD, which he commanded their ancestors by Moses. 5 So the Israelites lived among the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites; 6 and they took their daughters as wives for themselves, and their own daughters they gave to their sons; and they worshiped their gods.

Part of the reason to attempt to write history is to make sense of both the past and the present. Throughout the first two chapters have been setting the scene where the tribes of Israel remain with the various Canaanite and non-Canaanite peoples continuing with their own gods, practices, and in many cases their land and cities. The first two chapters have laid the blame on the Israelites and their unfaithfulness to God’s instructions. Chapter three begins with two explanations for the presence of these people among Israel: that they may learn how to fight and to be a test for the people of Israel. If one assumes that the people have the law as it is outlined in the book of Deuteronomy there is instructions on how to properly conduct war as the covenant people (Deuteronomy 20: 10-18) but that particular portion of Deuteronomy also designates the very people listed in verse five are designate for annihilation (herem). Yet, the very opposite happens here when the daughters and sons of Israel intermarry with these people and worship their gods.

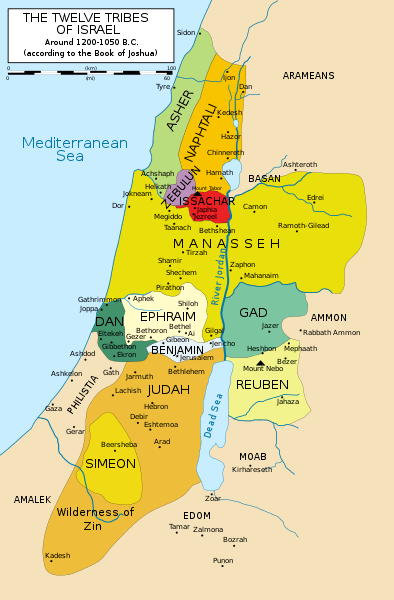

Within this brief passage there are two list of remaining nations. The first list includes the Philistines who are also a people who recently conquered and settled in the land. The Philistines were a sea faring people who came from the Mediterranean (traditionally traced back to Crete) and develop an alliance of five city states (Ashodod, Ashkelon, Ekron, Gath, and Gaza) along the southwestern edge of the territory that Israel claims. The Canaanites is a general term for the peoples that already existed in the land. The Sidonians were Phoenecians who lived along the Mediterranean on the northwestern edge of Israel’s territory (they are named for the town of Sidon) while the Hivites lived in the mountainous terrain presumably in north Israel and southern Lebanon. The second list is the traditional designation of the seven nations of the Canaanites as listed in Deuteronomy 7:1, although the Girgashites are not present in Judges or Deuteronomy 20.

The situation where the boundaries of Israel are blurred by the presence of people who worship different gods and have different practices of life is compounded when the boundary of tribe and family are blurred by intermarriage. The bible has multiple perspectives on this. In general, the Hebrew people were discouraged from intermarrying with other peoples, especially the Canaanites whose land they were entering. Books like Ezra and Nehemiah blame intermarriage for the state of the nation, while Ruth tells the story of the faithful foreigner who marries a Jewish man and adopts the practices of the covenant people. We know that intermarriage happened, and was probably a regular occurrence throughout Israel’s history but the danger was that the sons and daughters of Israel would then adopt the practices and worship of the other peoples instead of these new sons and daughters being integrated into the covenant life of the chosen people of God.

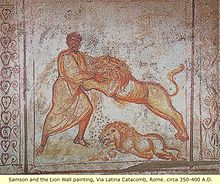

Judges 3: 7-11 Othniel the First Judge (from Judah)

7 The Israelites did what was evil in the sight of the LORD, forgetting the LORD their God, and worshiping the Baals and the Asherahs. 8 Therefore the anger of the LORD was kindled against Israel, and he sold them into the hand of King Cushan-rishathaim of Aram-naharaim; and the Israelites served Cushan-rishathaim eight years. 9 But when the Israelites cried out to the LORD, the LORD raised up a deliverer for the Israelites, who delivered them, Othniel son of Kenaz, Caleb’s younger brother. 10 The spirit of the LORD came upon him, and he judged Israel; he went out to war, and the LORD gave King Cushan-rishathaim of Aram into his hand; and his hand prevailed over Cushan-rishathaim. 11 So the land had rest forty years. Then Othniel son of Kenaz died.

The story of the first judge, Othniel, is short but it sets the pattern for the narration of the judges that come afterwards. Dennis T. Olson points to six elements that give a pattern to evaluate the stories that follow:

(1) the nature of Israel’s evil, (2) the description of the enemy’s oppression, (3) God’s reaction to the Israelite’s cry of distress, (4) the judge’s success in uniting and delivering Israel, (5) a focus on God’s victory or the judge’s personal life, and a desire for vengeance, and (6) the proportion of the number of years the judge ruled in peace (the land had rest for “X” years) (NIB II: 766)

Just as Othniel will set the pattern for the evaluation of future judges, he will also in many ways be the model of what a judge should be. The Israelites at this point are not a nation and the actions of each judge are primarily oriented around individual tribes, and so with Othniel we are primarily looking at the territory of Judah.

The refrain. “The Israelites did what is evil in the sight of the LORD,” serves as a transition between each of the major judge narratives. The evil the Israelites have done is listed as two-fold: they forget the LORD their God, and they turn to other Gods (Baals and the Asherahs). The previous two chapters and the beginning of chapter three have all set the stage for the people integrating with the people who existed in the land, adopting their practices, and intermarrying with them. Now for the first time the people experience oppression under a foreign leader.

King Cushan-rishathaim (Cushan of the double wickedness) who comes from Aram-naharaim (Aram of the two rivers) is an unknown leader in the historical record outside the bible who comes from the area in modern day Syria or Iraq between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. This doubly wicked king causes problems for Israel (or at least a portion of Israel) for eight years. The oppression of this ‘wicked’ ruler causes the people of Israel to remember their God and to call out to their God by name.[1] The LORD the God of the Israelites is a God who hears the cry of the oppressed and feels compelled to respond to that cry.

The spirit of the LORD comes upon Othniel to deliver the people. We encountered Othniel in Judges 1: 11-15 and he is the final linkage to the generation that came into the land. In contrast to the Israelites who intermarried, Othniel’s wife is an Israelite and the daughter of the illustrious Caleb, second in respect among the previous generation to only Joshua. There is little narration of the conflict between Othniel and Cushan-rishathaim beyond the spirit of the LORD coming upon Othniel and delivering this foreign king into his hand. Yet, this action of the LORD to deliver the people through Othniel brings forty years of rest in Judah.

Judah in the first chapter of Judges was the most successful in gaining control of its territory and here the judge from the people of Judah is successful in bringing a sustained period of peace after a relatively brief period of oppression (in comparison to the other stories of the judges). Othniel’s narrative is short and compact but it also sets the pattern for all other judges to be evaluated against. Yet, with the death of Othniel the people of Judah, and Israel, lose their connection with the generation that experienced God’s work to bring them into the land. In the absence of a leader to unite them they quickly lapse into the pattern of doing evil in the sight of the LORD again.

Judges 3: 12-30 Ehud the Second Judge (from Benjamin)

12 The Israelites again did what was evil in the sight of the LORD; and the LORD strengthened King Eglon of Moab against Israel, because they had done what was evil in the sight of the LORD. 13 In alliance with the Ammonites and the Amalekites, he went and defeated Israel; and they took possession of the city of palms. 14 So the Israelites served King Eglon of Moab eighteen years.

15 But when the Israelites cried out to the LORD, the LORD raised up for them a deliverer, Ehud son of Gera, the Benjaminite, a left-handed man. The Israelites sent tribute by him to King Eglon of Moab. 16 Ehud made for himself a sword with two edges, a cubit in length; and he fastened it on his right thigh under his clothes. 17 Then he presented the tribute to King Eglon of Moab. Now Eglon was a very fat man. 18 When Ehud had finished presenting the tribute, he sent the people who carried the tribute on their way. 19 But he himself turned back at the sculptured stones near Gilgal, and said, “I have a secret message for you, O king.” So the king said, “Silence!” and all his attendants went out from his presence. 20 Ehud came to him, while he was sitting alone in his cool roof chamber, and said, “I have a message from God for you.” So he rose from his seat. 21 Then Ehud reached with his left hand, took the sword from his right thigh, and thrust it into Eglon’s belly; 22 the hilt also went in after the blade, and the fat closed over the blade, for he did not draw the sword out of his belly; and the dirt came out. 23 Then Ehud went out into the vestibule, and closed the doors of the roof chamber on him, and locked them. 24 After he had gone, the servants came. When they saw that the doors of the roof chamber were locked, they thought, “He must be relieving himself in the cool chamber.” 25 So they waited until they were embarrassed. When he still did not open the doors of the roof chamber, they took the key and opened them. There was their lord lying dead on the floor.

26 Ehud escaped while they delayed, and passed beyond the sculptured stones, and escaped to Seirah. 27 When he arrived, he sounded the trumpet in the hill country of Ephraim; and the Israelites went down with him from the hill country, having him at their head. 28 He said to them, “Follow after me; for the LORD has given your enemies the Moabites into your hand.” So they went down after him, and seized the fords of the Jordan against the Moabites, and allowed no one to cross over. 29 At that time they killed about ten thousand of the Moabites, all strong, able-bodied men; no one escaped. 30 So Moab was subdued that day under the hand of Israel. And the land had rest eighty years.

The second judge comes for the tribe of Benjamin which although a southern tribe was not asked to ally itself with Judah and Simeon and remains unable to drive out the Jebusites from Jerusalem. The period of oppression is also longer before the people call on the LORD and so the people are subject to King Eglon of Moab for eighteen years, ten years longer than before they call on the LORD and the LORD provided Othniel. Now instead of an upstanding member of a family with a history of faithfulness and an individual with previous military success God provides this ‘left handed son of the right hand.’[2] This short narrative of Ehud and Eglon is full of satire and humor but it is also the story of God working through a trickster, something that has happened before and continues to happen in the scriptures.

Names often give additional humor to the story. As mentioned above Ehud is a left handed man in the tribe of the ‘son of the right hand.’ King Eglon whose name in Hebrew is related to ‘young bull’ or ‘fatted calf’ in combination with his obesity is portrayed as a sacrificial beast. We often bring our modern ideals of combat into ancient scenes, but King Eglon may have been a powerful warrior in his day. The tactics which relied on spears, shields, and probably chariots were not as reliant on agility as the sword fighting you see in movies or video games. This ‘young bull’ may have been as strong as an ox, even with his massive girth. He also is able to form alliances with the Ammonites and Amalekites and is able to hold territory once secured by Israel, reoccupying the city of palms (presumably Jericho which has not been rebuilt under Israel). It is also important to note that Ehud could not have approached the territory of Benjamin without passing through the territories of Reuben and Gad on the opposite side of the Jordan River. (Hattin 2020, 29)

Ehud makes a short two-sided sword which is a cubit[3] in length. This sword is short enough to be concealed on the right thigh, but the reality of a left handed assassin also plays into the story since most guards would look for a blade on the left side where a right handed fighter would draw it from. Ehud brings a tribute[4] to King Eglon. The Israelites in Judges have been reluctant to worship the LORD and provide their God tribute so now they find themselves providing what should have been used in the worship of their God in the service of a foreign king. Ehud sends the bearers of this tribute away but at the stones/idols[5] of Gilgal he turns back towards the house of King Eglon. Gilgal has already appeared in Judges as a place where a message from God is delivered by a messenger (2:1) that God will no longer deliver the people, but now from Gilgal God’s deliverance comes in this secret word delivered by Ehud. He bears a secret word[6] from a god[7] for the king. The king dismisses his attendants and waits for this secret word.

Much later the book of Hebrews will state,

“Indeed, the word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing until it divides soul from spirit, joints from marrow; it is able to judge the thoughts and intentions of the heart. “(Hebrews 4:12)

But here the ‘word’ is a two-edged sword in a non-metaphorical way. This short sword is swallowed up by the obesity of the king and in a bit of ‘scatological humor’[8] and this humor is extended by the followers of Eglon delaying their entry of his chamber assuming he is using the chamber pot. The ‘dirt’ coming out is probably excrement and perhaps the smell also causes the followers of this corpulent king to assume their master is relieving himself in the coolness of the chamber. Their delay allows for Ehud to escape and rally the people of Benjamin and Ephraim to trap the Moabites on the western side of the Jordan River. After a massive military defeat Moab is subdued and the Israelites (at least in this region) enjoy an extended period of peace (eighty years).

This second story of a judge has a much different tone than the first. The story of Ehud and King Eglon is the story of a trickster assassin and bathroom jokes that probably provided entertainment for generations of storytellers and hearers. The morality of the bible is strange to us, but it values the clever trickster. From Jacob the heel grasper (later renamed Israel) to the spies at Bethel who make a deal with a man of the city to bypass the city defenses, (Judges 1:22-25) to the narrative of Samson and many others the bible includes many stories of tricksters who are a part of God’s purpose. The character of the trickster is often valued in ancient stories where people (or animals) find clever ways to thwart a superior opponent and the bible includes several of these stories. The assassination of the King leads to a dramatic change in the ability of the Moabite alliance to continue to oppress the Israelites and is viewed as an extension of God’s action to deliver the people from their oppression. God in Judges may work through strange agents who act in strange ways, but Ehud is viewed in a positive light among the judges of Israel.

Judges 3: 31 Shamgar the Third Judge

31 After him came Shamgar son of Anath, who killed six hundred of the Philistines with an oxgoad. He too delivered Israel.

With Shamgar we encounter the first minor judge and the first conflict with the Philistines. Shamgar is only mentioned here and in the song of Deborah (Judges 5:6) and his mention in that song may be the reason for his inclusion here. Shamgar may not be an Israelite and yet he may be lifted up as one through whom God delivers Israel from the Philistines. Anath is the name of a Canaanite female warrior goddess and there is some evidence from early Iron age Palestine that may point to the existence of a warrior class associated with Anath.[9] The Philistines were technologically advanced having iron chariots and weaponry and so the humiliation of this feared enemy by a warrior bearing a long staff used as a cattle prod makes a mockery of the superior weaponry of their opponent. It is possible that this is the first explorations of a Philistine military unit exploring the territory of the Canaanites and the Israelites and Shamgur’s actions delay the ultimate occupation by force of the Philistines in the region. [10]Yet, the inclusion of a judge who may not be an Israelite and may be the devotee of a Canaanite god is surprising among the twelve judges in this book. Already of the three judges, the God of Israel has worked through a trickster assassin and perhaps through a cattle prod wielding foreign warrior who is devoted to a Canaanite god. Yet, the book of Judges also assumes the God is at work in allowing the various kings and nations to rise up and oppress the tribes of Israel as a punishment for their disobedience, so perhaps including a non-Israelite as a deliverer of Israel is not as strange as it initially appears.

[1] Any time the Old Testament/Hebrew Scriptures uses LORD in all capital letters it is a reference to ‘YHWH’ the name of God spoken to Moses at the burning bush. Throughout the scriptures the vowels are changed to give the reader the clue to say ‘Adonai’ (Lord) instead of pronouncing the divine name (Yahweh). Yet, each time we encounter this naming of God we are referring to specifically the name of the God of Israel.

[2] Benjamin means ‘son of the right hand’ so the story begins its introduction of irony with indicating that this Benjaminite is left handed.

[3] The term for cubit (gomed) only occurs here in the Old Testament/Hebrew Scriptures. This may be shorter than the standard cubit (from elbow to fingertip) typically noted by the Hebrew ‘amma and may refer to the length from elbow to knuckles. (Webb 2012, 171)

[4] The term for tribute (minha) is usually used in scripture for an offering presented to God. (Webb 2012, 171)

[5] This word likely refers to carved stones set up for a shrine or idols, and it is likely that Gilgal is considered a ‘holy place’ where a divine message may occur.

[6] In classical Hebrew wordplay the Hebrew dabar typically means ‘word’ but can also refer to a ‘thing’

[7] In speaking to King Eglon Ehud does not speak specifically of the God of Israel but uses the generic term for ‘a god,’ the king likely assumes it is from one of the gods represented at the shrine/idols of Gilgal.

[8] Scatology is the study of feces, and scatological humor is often looked down upon in proper societies, but the Hebrew Scriptures seem to have no problem using excrement to make light of their enemies.

[9] Bronze arrowheads were discovered from this time inscribed with a warrior’s name as the ‘son of Anath’ (Webb 2012, 177)

[10] Barry Webb makes this suggestion based on the number six hundred commonly designating an organized force under a commander and provides numerous examples from first and second Samuel that support this hypothesis. (Webb 2012, 177)